|

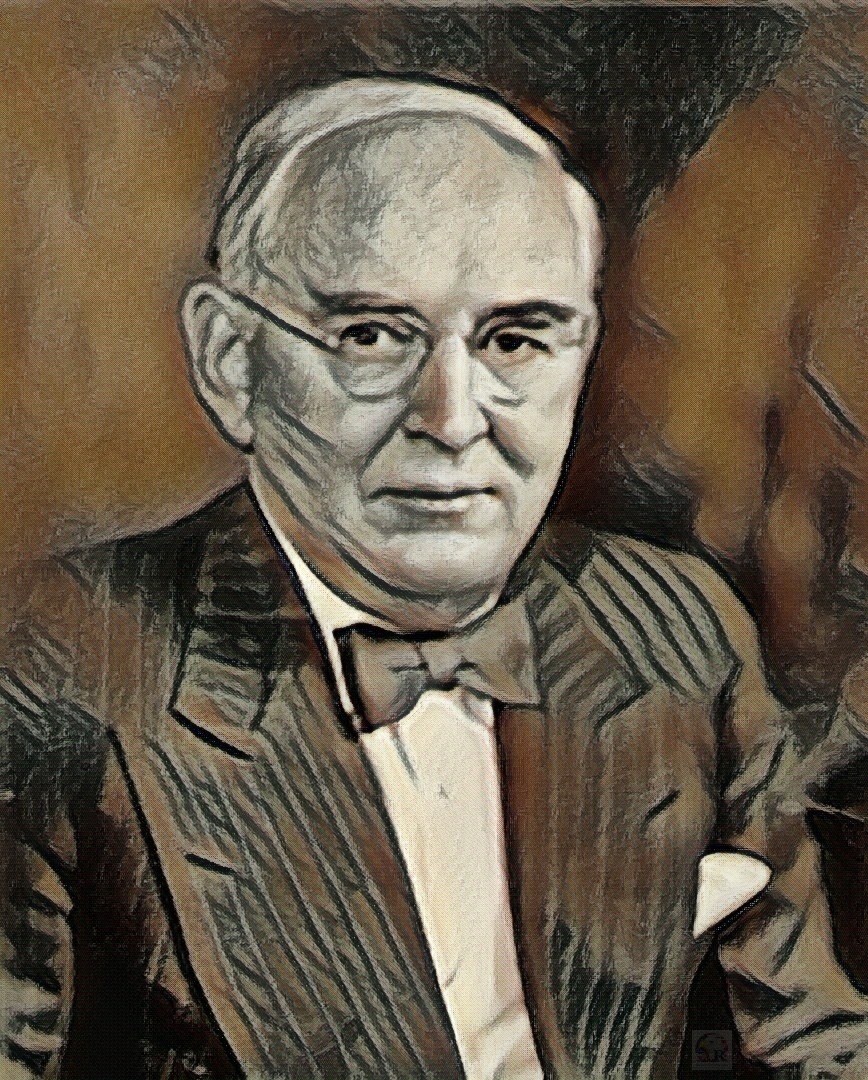

Arthur Vandenberg Address to the Cleveland Foreign Affairs Forum delivered 11 January 1947, Cleveland, Ohio

Mr. Chairman, I congratulate the Cleveland Forum upon the powerful program it has produced from all quarters of the globe in a striking exchange of international opinion. This process of reciprocal candor is one of the major forces which can beat swords into plowshares on the anvils of mutual understanding and good will. Indeed, this is the supreme potentiality of the organized United Nations. War will remain at a heavy discount so long as international controversy stays in the council chamber and adversaries talk things out instead of shooting them out. It was my good fortune to coin a phrase at the United Nations San Francisco Conference in 1945 which seems to survive. I prophesied that the General Assembly would become the town meeting of the world. In 1 year it has become exactly that. So long as the town meeting meets, reason is calculated to outweigh force. So long as this safety valve works, the world’s boilers are not calculated to explode. Peace with justice is the dearest aspiration at every hearthstone in the world. Here in your town meeting the voices of global hope have joined in this universal prayer. The voice of our own America must rise above them all, not only because our people deeply share this dedication, but particularly because time and events have given us the tremendous responsibility of a spiritual leadership which most of the world is eager to have us grasp and which we would desert at our own peril. Tonight, according to your program, the United States replies to the world. So far as my little part in this symposium is concerned, this is too large an order to be filled in 30 minutes. Further, I must make it plain that I am not in a position to reply for the United States because the Constitution confides that prerogative exclusively to the President. The Senate merely advises and consents. Sometimes it doesn't even do that. Fortunately, the Secretary of State is here to speak for the President. But, unfortunately, he is shortly leaving the public service by resignation. I say this with deep regret. Secretary Byrnes has been an able, efficient, courageous Secretary of State in the finest American tradition. He has relentlessly defended American ideals in crises where they required defense. He has made a great contribution to the welfare of this country and to the peace of the world. I salute him with affection and profound respect; and I hail him as a very great American. General Marshall, who succeeds him, brings to his task a stout heart, a clear head, and a rich experience. He has always enjoyed the total confidence of Congress and of all his military and civilian colleagues at home and abroad. I wish him well in his great responsibility. As a junior partner I have worked with Secretary Byrnes on what is called a "bipartisan foreign policy" in the United Nations and in planning European peace. It would be more significant to say we have sought a united American foreign policy so that, despite some inevitable dissidence at home, America could enjoy abroad the enhanced authority of a substantially united front. I dare to believe that, despite some distressing domestic interludes, it has borne rich fruits. In any event, partisan politics, for most of us, stopped at the water's edge. I hope they stay stopped -- for the sake of America -- regardless of what party is in power. This does not mean that we cannot have earnest, honest, even vehement domestic differences of opinion on foreign policy. It is no curb on free opinion or free speech. But it does mean that they should not root themselves in partisanship. We should ever strive to hammer out a permanent American foreign policy, in basic essentials, which serves all America and deserves the approval of all American-minded parties at all times. The State Department and the Foreign Service themselves require broad-gauged reorganization to keep pace with America’s unavoidable world responsibilities, and particularly to develop more long-range planning so that there need be less catch-as-catch-can improvisation and expediency. Our top representative in the United Nations should be a permanent Under Secretary of State. But let me get back to that reply to the world. I assume the world chiefly wants to know whether America will persist in its attitudes toward collective peace and security. I cannot answer for others, I will answer for myself. I believe the United States, in enlightened self-interest, will do everything within its power to sustain organized international defense against aggression; to promote democracy and human rights and fundamental freedoms; and, through international cooperation, to seek peace with justice in a free world of free men. We plot no conquests. We shall neither condone nor appease the conquests of others. We ask nothing for ourselves except reciprocal fair play. The extent to which it develops will determine our final course. We are not interested in unity at any price. We shall aspire to standards which will rally others to match our zeal. We offer friendship to all. Our reply to the world is a challenge to match us in good works. Mr. Chairman, these American attitudes will persist because they stem from reason and reality, and we are a practical people. We should remind ourselves, as well as our neighbors, from time to time, of certain facts in this connection lest we suffer in steadfastness what we lose in recollection.

Prior to December 1941 we were

conscientiously divided, along lines of deep conviction, regarding our

proper role in a world at war just as we were similarly divided 20 years

before regarding our proper role in a world at peace. Pearl Harbor ended

that debate. It brought a united country to far-flung battle lines where

we swiftly mobilized the greatest fighting resources of all time. It did

more. It released an evolution which drove most of us to the

irresistible conclusion that world peace is indivisible. We learned that

the oceans are no longer moats around our ramparts. We learned that mass

destruction is a progressive science which defies both time and space

and reduces human flesh and blood to cruel impotence. Then we

contributed the crowning proof ourselves. In the climax of this tragedy

we ourselves devised the atom bomb -- an appalling tribute to our

illimitable genius -- an equally appalling prophecy of civilization’s

suicide unless World War Three is stopped before it starts. This

produced the inevitable conviction that the jungle code of war must be

repealed for keeps.

Before the horrors of the conflict had even reached their maximum we brought our major allies together at Dumbarton Oaks to chart the most essential victory of all -- a victory over war itself. Oh, yes, we had said these same things once before and they had turned to ashes on our lips. But there is no comparison in the provocation which was our immediate spur. From Dumbarton Oaks we went to San Francisco and at the symbolic Golden Gate the Charter of the United Nations was unanimously approved. From San Francisco we went to Washington and the Senate spectacularly ratified the Charter with but two dissenting votes. We accepted the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice. From Washington we went to London and organized the first town meeting of the world. From London we came back to New York, where, in response to congressional invitation the United Nations launched its gigantic adventure on a site in the United States, which thus gives us the permanent peace capital of the world. This record cannot be misread at home or abroad. We have embraced the United Nations as the heart and core of united, unpartisan American foreign policy. We shall be faithful to the letter and the spirit of these obligations. In my view, this will be true no matter what administration sits in Washington, and it will remain true to whatever extent the United Nations themselves are faithful to our common pledge. That, in general, Mr. Chairman, would be my overall reply to the world. But I make the reply with no illusions that now all's well. The United Nations is neither an automatic nor a perfect instrument. Like any other human institution, it will make mistakes. It must live and learn. It must grow from strength to strength. it must earn the ever-expanding confidence and fidelity of people everywhere. It must deserve to survive. Meanwhile, it is definitely beset by hazards For example, the necessity for unanimity among the Five Great Powers is both strength and weakness to its arm. Strength, because these Great Powers when united are invincible. Weakness, because the excessive use of the veto, particularly in respect to the pacific settlement of disputes, can reduce the whole system to a mockery. It is much too early to talk about major surgery on the Charter itself. But I hope all the Great Powers will voluntarily join in a new procedural interpretation of the Charter to exempt all phases of pacific settlements from what, in such instances, makes of the veto a stultifying checkmate. I pose this as a test of international good faith. There is another hazard. The organization is beset by fiscal dangers. In the enthusiastic eagerness with which it expands its nobly meditated efforts through specialized agencies, each with its own uncoordinated autonomy, it threatens accumulating, annual assessments which a majority of its member nations soon may be unable to fairly share. In such event, either the burden is concentrated on a few large states or the smaller states drop out. In the former case, the sovereign equality of member states will disappear. In the latter case, the United Nations will become a rich man’s club and its greatest genius -- universality of membership -- will disappear. Stern fiscal control is indispensable -- not penury but prudence. But, Mr. Chairman, we must not be impatient. It took 5 years to take the world apart. It would not be surprising if it took at least that long to put it together again. The remarkable thing is that the United Nations has done so well so soon, Its Security Council has already peacefully tempered many critical situations which, in the absence of its mediation, invited serious implications. The recent dispatch of a committee of inquiry to the Greek border is the latest striking case in point. Meanwhile, its General Assembly has already initiated powerful movements for the common good -- incomparably the greatest of which is an approach to mutual disarmament. These things can be the beginnings of the greatest benediction of all time. They are worth every effort which men of good will can muster. And let’s always remember this: The more imponderable the world’s frictions may become, the greater the need to persevere in strengthening this one and only available agent of organized emancipation, And this: If, one day, some aggressor leaves the United Nations, in order to be free of its restraints, the rest of the world has ready-made at hand the well-geared machinery for another, and immediate, grand alliance, swiftly and overwhelmingly to confront the offender. Would-be international assassins, if ever such there be, will not lightly chance such condign disaster. I spoke of disarmament factor is of such vitality; better typify America’s attitude toward peace and the world. We are prepared to disarm (1) to whatever extent other powers are dependably ready to make comparable, permanent, and effective renunciations; or (2) in whatever degree the United Nations and its cooperative military resources prove hereafter to offer a reliable substitute. It is our dearest dream. But we shall not dream ourselves into a nightmare. We shall not disarm alone. We shall not trust to the persuasion of our example. We tried that once before. We shall take no sweetness and light for granted in a world where there is still too much iron curtain We shall not trust alone to fickle words. Too many words at Yalta and at Potsdam have been distorted out of all pretense of integrity. We shall not ignore reality. We do not intend to be at anybody's mercy; nor do we intend to emasculate our authority with those who may still think in terms of force. But we will joyfully match the utmost limits of mutual disarmament to which other Titans will dependably agree, if there be disciplines which guarantee against bad faith; and we will speed the day when such a boon shall deal war its deadliest blow. I repeat, however, that this cannot happen either in ambush or on a one-way street. Our American proposals regarding atomic bombs illustrate my point. With an investment of $3,000,000,000 in this supreme destroyer of all time, and with a monopoly upon its sinister secret for some years to come, we offer not only to abandon our dominant advantage but also to join in outlawing its destructive use by anybody, any time, anywhere on earth. And what is our price? Just this -- an effective system of continuous inspection and control which makes certain that no international brigand shall hereafter break faith with us and with the world. The price is simply protection against treachery. But it is a fixed price, Mr. Chairman, and the price must be paid. We ask nothing for ourselves. We ask everything for peace. I submit, sir, that never had there been a comparable example of national good will, nor one so thrillingly dramatizing the purpose of a great people to live and let live on a peaceful earth, if we are allowed to do so. Now, Mr. Chairman, I briefly touch upon another phase. The economic factors of the peace are of vital interest to the world -- and us. Peace and economics are inseparably kin. Unfortunately this area of action: is not so clear because the premises themselves are mixed in a clash of economic ideologies. But we shall not draw back from our essential responsibilities. For example, I am sure Congress will make a liberal relief appropriation -- to be administered under American auspices in consultation with the United Nations -- for the stricken postwar areas which are still war casualties, even though we never again contribute 72 percent of an international fund, as in UNRRA, [United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Association] which can be controlled and even exploited by others. This is said without prejudice to the great and humane achievements of UNRRA despite its handicaps. Again, reasonable rehabilitation credits are unavoidable if democratic stabilities are to be restored before it is too late. By way of another example, I believe we shall continue the device of reciprocal trade agreements, in one form or another, to release and expand mutual trade -- an even greater need for us than for any Other country because our vastly expanded national economy and employment require it. Whether this can continue on its present multilateral basis will depend somewhat upon the type of competition we confront from foreign state monopolies and from a growing habit abroad of making bilateral agreements for political as well as economic purposes. These habits could force us into defensive tactics which we would not voluntarily embrace. We shall fit our procedures to the necessities which are forced upon us. Certainly we intend to keep our own American industry and agriculture in sound, domestic health, and to protect our system of free enterprise. Anything less would be a calamity not only for us but for the Western World. But sane, healthy, mutual trade expansion is best for all concerned. Mr. Chairman, my time runs out though I have touched only the outer rim of our mutual problems with the world. I conclude with a few swift overtones. We have finished five treaties with ex-enemy European states. They passed in review before a peace conference of 21 nations in Paris. We are entitled to say that this broad consultation of all our battle allies was an achievement primarily due to American insistence. Here, again, is an unmistakable cue to our international disposition ever to recognize the rights of little states as well as big. Here also is a cue to what seems to be our improved relations with the Soviet Unions -- as a result, I believe, of our present rugged policy of firm but friendly candor which I hope has permanently established the American doctrine that there are deadlines in our ideals from which we shall never again retreat. This is not truculence; it is the power of brave and naked truth. When we left Paris in September the Council of Foreign Ministers was deadlocked on more than 40 issues. When we left New York in December they were all amicably resolved. These five treaties are far from satisfactory in many aspects. But they bear no remote resemblance to the greater dissatisfactions which we have prevented, and they are a great advance toward reconstruction in a peaceful world.

Now we turn, after many weary months of urging, to peace plans for Austria and Germany. At long last, we shall come to grips with the heart of the European problem. All occupying powers should recognize the independence of Austria and withdraw their troops. In Germany, retarded by Russian and French refusals to fulfill the Potsdam requirement that the four zones of German occupation should operate as an economic unit, the German situation has suffered such economic deterioration as to threaten chaos and disaster. We have partially met this worsening crisis by unifying the American and British zones -- with an invitation to the French and Russians to join us at their option. This is a hopeful pattern. Meanwhile, the business of renewed, decentralized political autonomy -- looking toward federated states which shall be the masters and not the servants of a new Berlin -- makes encouraging progress in the American zone. But the pressing need is a plan for total peace -- a plan which omits no possible precautions against recurrent Hitlerism, yet which offers some reward other than eternal degradation to new German states when they faithfully strive toward democratic self-redemption. The important thing for the world to know is that we intend to remain in occupation until this job is done. It is part of the war, if we are to preserve our victory. Meanwhile, we face the intimate necessity of refreshing our indispensable pan-American solidarity. This comes close to home. It is historically basic in American foreign policy; and nothing has happened to lessen the importance of these good neighborly contacts. Quite the contrary. At San Francisco, 20 Latin-American Republics were unwilling to proceed with the United Nations Charter until the validity of our historic regional arrangements were Officially tied into the United Nations plan. This was specifically done in chapter VIII of the Charter. Thereupon, the then Secretary of State, Mr. Stettinius, as part of the agreed plan, promised

That was on May 15, 1945. This is January 11, 1947. “In the near future” has not yet arrived. The Secretary said of the proposed conference that “it would be another important step in carrying forward the good-neighbor policy.” If he was right -- and I think he was -- this long failure to hold the conference has had the opposite effect. I am well aware of the reasons for delay. I entirely sympathize with the anxiety to purge the Americas of their last vestige of Nazism. But I think that, under a dozen solemn pan-American treaties to which we are a party, this is a multilateral decision which should always be made by all of us jointly and not influenced or dictated by us alone. In some aspects it can be said that we have been proceeding jointly. But I think it is past time to hold the Pan-American conference which we promised in 1945, and there to formally renew the joint New World authority which is the genius of our New World unity. There is too much evidence that we are drifting apart -- and that a Communistic upsurge is moving in. We face no greater need than to restore the warmth of New World unity which reached an all-time high at San Francisco. I devote a few parting sentences to the Far East, where General MacArthur is doing so magnificent a job in Tokyo that our daily headlines scarcely remind us that we are successfully liquidating the greatest single postwar task which fell to our primary responsibility, and where the young Philippine Republic arises as a monument, not only to its own vigorous self-development but also to our steadfast, anti-imperialistic American liberalism, which defies successful libel, either at home or abroad. But it is particularly China to which I dedicate this paragraph. Here lies a vast and friendly republic, rich in wisdom, equally rich in its democratic promise for tomorrow, and historically fixed in the orbit of our good will. Since 1911, when Dr. Sun Yat-sen gave China her new vision, she has been struggling, against bitter odds, toward the light of a new day. While recognizing the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek, we have -- through a year's mission headed by our distinguished General Marshall -- been impartially urging that it produce unity with a rival armed party -- the Chinese Communists. Under the determined leadership of Chiang Kai-shek, a national assembly has just produced a new constitution and the government has been reorganized with a coalition of non-Communist parties. We can hope that this Nanking [or Nanjing] charter, with its first great national election promised before next Christmas, will weld together a strong and competent China. It is my own view that our own far-eastern policy might well now shift its emphasis. While still recommending unity, it might well encourage those who have so heroically set their feet upon this road, and discourage those who make the road precarious. Our marines, having finished their task, are coming home. But there will never be a minute when China's destiny is not of acute concern to the United States and to a healthy world. My fellow citizens, we face a new year in world affairs, with many gnawing problems still unsolved all round this turbulent globe. I have touched only a few which have special significance in respect to the topic of the evening. Peace is more difficult to win than was the war. Even we ourselves cannot yet claim convalescence. It is not strange if other lands, torn asunder by physical destruction, desperately rocked by disintegration, perhaps still ridden with alien troops and unwelcome overlords, perhaps unable to reerect their family shrines, reunite their families or even find decent subsistence for their families, perhaps unable to resist the subversive invasion of alien tyranny and terrorism -- it is not strange if other lands are prey to a restlessness which stalks the earth and offers sanctuary to creeds of deliberate chaos and confusion. There is nothing but peril -- for the United States of America -- in neglecting our vigilant attention to these ugly facts. On the other hand, we have a right to clear ourselves with some very real encouragements. he greatest of these -- and I end as I began -- is the luminous fact that 55 nations are committed by solemn covenant to help each other keep the peace, to substitute law for force, and to strive toward the uplift and defense of human rights and justice and fundamental freedoms. The world has far to go before this pledge is a reliable reality. But the United Nations has raised this standard to which men of goodwill in every clime and under every flag can repair, and it has already sped us on this God-blessed way. America will do her full part.

1 Statement by Hon. Edward R. Stettinius, Jr., Secretary of State. The Charter of the United Nations Hearings, July 9-13, 1945. Original Text Source: 1947 Congressional Record, Volume 93: Cong. 80 Sess. 1 at the Internet Archive

Original Image Source: senate.gov

Page Created: 3/31/21 U.S. Copyright Status: Text and Digitally Enhanced Image = Public domain. |

|

|

© Copyright 2001-Present. |