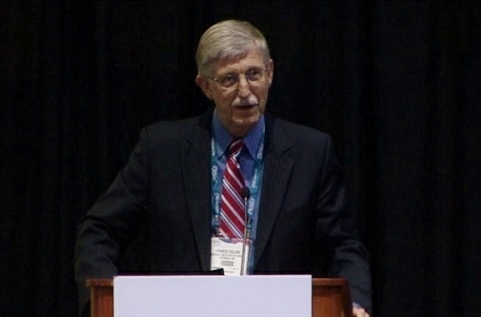

Dr. Francis Collins

PGH 146-A 400 Keynote Address on Global Health Initiatives

delivered 27 June 2011, Washington, D.C.

[AUTHENTICITY CERTIFIED: Text version below transcribed directly from audio]

Well, thank you, Steve, for those kind words and it's a real pleasure to be able to speak to this distinguished and international group about some thoughts from the NIH director in the area of global health research.

It's always awkward to come and try to give a keynote address at a session that's been going on for several hours when you've only just arrived. But I will do my best to try to give you some perspectives and hope you will forgive me if I am duplicating information that others have already highlighted effectively. And I hope I will not find myself in utter conflict with things that had already been resolved earlier in the afternoon and throw the whole area into disarray. I will try not to do that and I think there should be some time for some discussion afterwards, which I will very much look forward to.

It is an enormous privilege and an enormous responsibility to stand at the helm of this largest supporter of biomedical research in -- in the world. And as I contemplated what exactly might be special opportunities to emphasize when I came to this job a little less than two years ago, global health research was very much one of the top five themes that I wanted to see emphasized.

I have to tell you for me having carried out some activities in that area and having also volunteered as a volunteer physician in developing countries, I was impressed and also a little daunted by the complexity of the landscape here in terms of the areas of research that many different organizations are contributing to. And I think it continues to be a bit of a challenge with so many individuals and organizations working in this space to be sure that we are making the most of the opportunity especially at a time where resources are not infinite and certainly they are not.

That ladder is certainly something that wakes me up in the middle of the night because we have so many scientific opportunities right now. And yet at NIH, we are facing particularly tight constraints on our ability to be able to fund all of the bright minds that come to us with their bright ideas and that forces us to really think hard about priorities and also to make sure that whatever we're doing is not duplicating other efforts. So it is because of the wonderful inputs that I'm able to get and particularly from the Fogarty International Center represented here by Roger Glass and Rob Eiss who have helped me with the ability to sort through those things. But I'm sure there are times where I donít quite get it right and I'm sure in the discussion, you'll uncover some of them.

So NIH is, after all, a organization that has a mission that crosses from basics to clinical research in a very explicit way. The first part of our mission statement talks about science and pursuit of fundamental knowledge. But the second part talks about the application of that knowledge to extend healthy life and reduce the burdens of illness and disability. And NIH has been deeply engaged in exploring that not only for our own country but across the world for a very long time. In that regard, I think when asked the question, as I was when I first mentioned that I thought global health research should be one of our priorities, well, why is that. After all, the taxpayers of the U.S. are paying for all of this. Why is global health research something that should be particularly paid attention to?

Well, scientifically, I think it is fair to say, we have exceptional opportunities, you know, across the board in infectious diseases, the ability to identify new interventions on the basis of knowing more about the pathogens that we need to go after are really quite exciting. We have the genome sequences of many of those pathogens and in fact the vectors that may have carried them off to us as the host and we certainly know a lot more about the host than we used to. And that gives us new ideas about targets for small molecule screening or vaccine development. And we have other technologies like RNAI that give us the chance to really take apart the pathways involved in pathogen biology. And that should position us more than ever to be able to make progress in global health with all of that information to guide us.

On top of that, now we have the chance to push beyond the big three of AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis because of many of these technologies to a long list of neglected tropical diseases and I will mention one or two along the way. And very importantly, we also have the opportunity and the responsibility to pay increasing attention to non-communicable diseases because that is, after all, the most rapidly growing area of morbidity and mortality and research is desperately needed there as well if we're going to do something about that frightening sort of trajectory.

And I think it's also particularly apparent now that the young generation of medical researchers has a passion for global health. Many of them having acquired this along the way in their training and see this as a real calling. And to be able to tap into that energy and that adventurous spirit is a -- a wonderful experience that I think we at NIH are trying to encourage in every way we can.

And of course then there is this sort of obvious, but maybe it hasnít been so obvious to everyone, connection that if NIH is investing in global health, it is actually self-serving for the U.S. as well. "Global is not the opposite of domestic."1 This is one favorite quote of mine from Julio Frenk. So what we learn in carrying out research in global health benefits our own citizens as well. So I think I can make a case from the perspective of all these points that NIH investments in global health are entirely justified and are a high priority right now in terms of the way in which we utilize the resources that the government gives us. And of course the NIH has been carrying out this kind of work for a long time.

This is a snapshot where all of the countries that currently have some level of funding from NIH are colored in in green. And you can see that's an awful lot of the world that has at least some support. This doesnít attempt to quantify it but simply to say that there is work going on there supported by this particular institution.

A lot of what we are able to do is greatly facilitated by the Fogarty International Center and by the network of researchers that had been trained through this program for clinical research scholars and fellows. And here you can see just by the colored dots on the map where the individuals in this photograph as a recent gathering are currently positioned or -- or have been. And that's just a small fraction of the total number of individuals who have been trained throughout the Fogarty program over many years. I always find whenever I travel internationally to a place where global health research is going on, there is quite a wonderful cohort of Fogarty trained individuals working there and I think that has been one of our most important contributions to this field.

So let's talk about broadening the vision of global health research from the perspective of NIH and I'm going to talk about a few topics. Certainly we should talk about the big three, HIV-AIDS, TB and malaria. And I'll particularly talk about HIV because it's been a very exciting time actually in the last year or two in terms of investments in research that are beginning to pay off in interesting ways. Neglected tropical diseases, non-communicable diseases and some innovative approaches to global health research that are not disease-specific but which we believe have the capability of increasing research capacity in the developing world. A critical agenda if we're going to see the future turn out the way we want it to.

So let me start with some comments about the big three and particularly about HIV-AIDS. Obviously, over the course of many years, NIH has been invested in lots of these kinds of studies and that have required us to build through NIAID quite an impressive network of clinical trial capabilities in multiple parts of the world. And that network turns out to be extremely valuable for things that have happened more recently. You can see the consequences of how the ability to prevent maternal-to-child transmission is playing out in terms of infections averted based on this 2009 summary and that curve continues to go up.

Other things that one can point to in terms of realization of benefits from research studies, in this case, dramatically more in efficacy, I think, than most people expected to see from circumcision. And that is certainly playing out now in many parts of Africa as I found when I travelled to Africa in March and saw the large number of clinics that have sprung up to offer circumcision to young males.

And then this publication just from late last year about how in fact this notion of pre-exposure chemoprophylaxis can in fact turn out to be quite beneficial for individuals at high risk and in this instance showing a 44 percent reduction in HIV incidents in the treated group and actually much higher than that in those that were shown to have high adherence to the therapy. So at least in this particular setting; and this is very much an international study in Brazil, Ecuador, Peru and South Africa and Thailand as well as the U.S.; it is clear that this kind of approach can provide real benefits.

And this study which made quite a splash just about a month ago, looking indeed at the circumstance where you have partners with one who is HIV-positive and the other is negative, obviously a situation where one can assess whether in fact treating the positive partner reduces transmission by reducing viral load, the effect here really quite dramatic. 96 percent reduction in HIV transmission certainly leading to the conclusion that if we had the resources and the system in place, the idea of trying to treat early after someone is HIV-positive could be of enormous benefit recognizing that the majority of new infections come from individuals who do not know that they are already positive and that that is a time where the viral load can be quite high.

All of these again are research studies that have been conducted largely through partnerships but led at NIH by NIAID, Tony Fauci and his very capable team. And then this, I think, a particularly exciting and rewarding thing to be able to see announced the ability to provide women in high incidence areas with an option to protect themselves and this of course being the tenofovir gel used to prevent HIV transmission as carried out by the CAPRISA study. I had the privilege of visiting with the people who led this study, Quarraisha Karim and other colleagues in Vulindlela back in March and to see the way in which they had conducted this really elegant and rigorously designed study in an area which is certainly out in the rural part of South Africa and yet done so -- so carefully with such participation by the community was really inspiring.

Again, I think most of you are aware of the results here. But this double-blind randomized control trial showed that in fact you could reduce HIV incidence by 39 percent by the availability of this gel. And clearly when this is the place in South Africa, this -- this age group where the incidence of becoming HIV-positive is frighteningly high. Having this particular opportunity provides really a major step forward.

An ongoing study called VOICE, Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic, is comparing safety and efficacy of tenofovir in gel versus oral tablet form with now 4,200 HIV infected -- uninfected women utilizing these various strategies to see what work. That's an ongoing study and others also in the microbicide pipeline. And then I want to say not only is it important in these kinds of real-world research studies to test out some new intervention of a pharmacological sort; they're also real opportunities to utilize cell phone technology, m-health approaches to assess just how the actual implementation is going. This is just one example of utilizing a pill box that actually connects to the cell phone network so that when the box is opened a signal is sent and it's possible for the clinic to see whether there is a problem or not with adherence.

And so here is a chart of an individual who is supposed to be taking this morning and evening. And the chart lets you know when the pill box was opened and things look pretty good. But there was some sort of a holiday taken from therapy here, which is not a good thing and that would provide an opportunity for the clinic to perhaps get a hold of the patient and find out what happened. Did you run out of pills? Did you somehow get a little distracted by other things?

In a circumstance like HIV-AIDS or like tuberculosis where long-term adherence is critical for ultimate success, this is going to be, I think, just one of many advances that can come out of the use of cell phones in creative ways and a great opportunity also for the kind of reverse innovation where what we may be able to learn in the developing countries can also be applied in high-income countries where cell phones are increasingly also available for medical care purposes.

Neglected tropical diseases, certainly that long list of conditions that are not on the list of the big three but collectively affect hundreds of millions of individuals, also I think are at an interesting and appropriate time for attention in terms of research effort. I just learned this afternoon about an announcement that will be made tomorrow, not to spill any beans, but about African sleeping sickness, which is one example of progress being made in this way by a creative effort to partner up with those organizations that have skills to make this happen.

The NIH effort in this area of neglected diseases is also ganged up with an effort in rare diseases and this is the program called TRND, Therapeutics for Rare and Neglected Diseases. It's a Congressionally mandated effort, modest in scale at the present time to speed the development of new drugs and particularly to move compounds through the Valley of Death on to clinical trials. It's an intramural/extramural collaboration. Projects enter at various stages of development, are taken far enough to be adoptable by a commercial partner and make a specific effort not to duplicate pharmaceutical projects. And TRND is encouraging, I think, some pretty interesting partnerships and novel approaches to intellectual property.

TRND, which has only been underway now for about two years, will become part of the new National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NCATS, when that enterprise stands up we hope on October 1st, and will bring into NCATS this focus on neglected diseases which TRND has already established along with a lot of other resources that would find their way into NCATS including a lot of clinical trials capability, as well as a focus on looking at the pipeline of drug development as an engineer would and trying to identify areas of optimization that havenít been fully explored.

I donít have slides to go into that detail. I talked about it at some length today in a different session on translational science. But an example would be the opportunity to rescue and repurpose compounds that have already been approved for one use and might find a new use if we knew enough to try them out in that way in the same way that AZT, having been developed for cancer and failed, turned out to be an -- a successful drug, the first one for HIV-AIDS. Or the same way that thalidomide, having been developed for morning sickness and causing terrible tragedies, is now a very effective drug in the use of -- against multiple myeloma.

There are lots of other kinds of repurposing and rescuing ideas that could be pursued more systematically if there was a home for that. And a recent discussion we had at NIH in April with pharmaceutical companies and biotech and academics indicated a lot of enthusiasm for pursuing this in a systematic way and something that we will, no doubt, want to push forward. NIH may be able to play a matchmaker role in this regard.

NIH may also be able to assist in this therapeutic development program in several other ways. One of which is by partnering more closely with our sister agency, the FDA, and assisting them in Peggy Hamburg's strong vision about how to promote more regulatory science to undergird their decision making and we already are co-supporting a research program with the FDA on that topic. We also have a leadership council that Peggy and I co-chair which consists of the leaders of the FDA's centers and our largest institutes working together to try to identify areas where we can help each other and have what is currently, as we all would acknowledge, a very long pipeline from initial idea to ultimate approval become shorter and also less expensive and less failure prone.

Coming back to TRND, the first pilot projects that were put into this pipeline are listed here, five of them. The first four that you see there are in fact rare diseases and the last one I particularly want to highlight because this is very much a neglected tropical disease, schistosomiasis, which is estimated to affect right now 250 million people across the world. A disease caused by a parasite which penetrates the skin if you happen to wade in the water where this parasite is present. After having cycled through its other host, which is a snail, then this gets into your system and invades the liver or sometimes the kidneys and causes a chronic and very debilitating circumstance for which there has been no new therapy available in some 50 years.

This is currently somewhat controlled by the current therapy that is 50 years old, praziquantel. But the cure rates are not 100 percent and there is evidence for the possibility of resistance that is increasingly a cause of concern. But we now know more about the schistosoma parasite in part because of the ability to look at its genome and identify the pathways that it depends upon in order to evade the host's ability to resist it. And one of those is that the schistosoma parasite makes a peroxidase which is actually an important part of its ability to withstand the host attack. So if you could knock out that peroxidase with a drug and of course pick a drug that doesnít hit the human peroxidase system, you might have something useful.

So David Williams, a grantee at that time at Southern Illinois University, worked with the -- the NIH Chemical Genomics Center, the NCGC, to design an assay and then to run a screen to see if compounds could be identified that would have activity. As a result of that, in fairly short order, it was possible to identify a whole class of drugs, [UNCERTAIN 19:26], and that appeared to have appropriate activity. Over here you can see the effectiveness, this in the mouse model of schistosomiasis. That is in fact the liver which is full of parasites in the control and here is the treatment.

Yeah, and over on the y-axis, you can't quite see it, is total number of worms. I've never published a paper where the y-axis was total number of worms. But this is the way you get results in this kind of disease and what a great result it is. You can see here XVIVO. This drug is very effective at killing the worms. So this has moved now into the pre-clinical stage of testing PK/PD and toxicology and hopefully will find its way into clinical trials in the not-too-distant future, again, as an alternative to the drug that's been out there for a long time and is beginning to show some signs of trouble.

That's just one example. One could certainly point to others. I should say that TRND has gone through a recent solicitation for new projects and they will be announced in the relatively near future. There are some five new ones that are coming in, one of which relates very much to a disease in the developing world. And there is a new solicitation which is due in -- in August. So if you're interested and have a project that might be benefited by this kind of partnership with NIH, have a look at the website for T-R-N-D. I tried that on my Google and if you go T-R-N-D, you'll go straight to this as your number one choice.

Not only, of course, do we have the need to develop new therapeutics but also various tools that would be valuable for diagnostics and that are applicable in low resource settings are an important part of the research agenda. Here is just one example. Again, tapping into cell phones as the means of transmission -- about the development of a lens-free microscope that allows you, and you can see the size here, to be able to look at microscopic images, transmit them through the cell phone in order to be able to make decisions about medical intervention without having to have onsite somebody who is a skilled cytologist or a microbiologist. Many other examples of that sort that are quite exciting to see getting developed.

I do now want to say something about non-communicable diseases because the growing threat of these disorders is certainly posing a challenge. So much of our focus in global health research has been, and understandably so, on infectious diseases. But as we are beginning to make some progress there, we are seeing on the other hand that we're losing ground for many of the diseases which have traditionally been considered more those of developed countries but which are finding their way into new settings. And some of them are pictured here; certainly trauma, certainly cigarette smoking and other dangers to societies across the world.

If you look at the data and this comes out of this paper in Lancet a couple of years ago, and obviously it's all projections from 2015 onward. But the estimates from these authors are that in the next 20 years or so we will see HIV-AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria drop back a bit. Other infectious diseases also drop back. Maternal, perinatal, and nutritional conditions, perhaps we'll make headway on. Accidents and injuries are actually getting somewhat worse. And then look at this; cancer, cardiovascular, and non-communicable diseases, a very significant increase and basically erasing what otherwise could have been a trend for the better.

So this demands our attention. It demanded our attention yesterday. If you read the press, and certainly if you were in D.C. and you read the Washington Post, you saw a report on the Lancet paper which was just published yesterday perhaps to coincide with the American Diabetes Association meeting showing that in fact the risk of diabetes across the world and not just in developed countries but in low-income countries as well is going up at a frightening rate.

And here again, this is a non-communicable disease which is something that is very much factored in the environmental changes that are occurring that we are exporting from developed countries to less developed countries and which are going to cost us enormously in terms of medical care, in terms of lost productivity, and in terms of misery and suffering of the people who are involved.

And it is certainly true that with diabetes, we're learning a lot more about the risk factors. We've discovered more than 40 hereditary factors that play a role in type-II diabetes. But it's certainly a disorder where a mainstay of prevention is going to be in the area of diet and exercise.

And we already know from studies that have been done in fairly controlled situations that that can be enormously successful if you can identify individuals who already have impaired glucose tolerance and are tipping over in the direction of diabetes and get them in a situation where they have adequate coaching to maintain a reasonable diet and exercise program, you can provide something like 60 percent reduction in ultimate going on to diabetes. How will we figure out how to export that kind of intervention in -- in low resource settings is something that we were desperately going to need to address. Otherwise, these curves are going to keep going up.

So some of the things that are happening in the regard of this growing global burden of chronic disease, certainly NIH very interested in this and we are an -- a participant in the Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases which has mounted its first program with multiple different funding agencies working together. The first program being focused on hypertension, another example of a circumstance where we understand pretty well that hypertension is a risk for stroke and heart disease. We know some of the things that can be done to intervene. We need to figure out how to actually implement those in all parts of the world that have not yet had that fully carried out.

And of course there's going to be much focus on this area of non-communicable diseases coming up in September with the U.N. summit which I think we are all looking forward to as a real opportunity for countries across the world to make a commitment to do something significant to stem the tide of what is really a very disturbing set of trends. Cancer is of course one of those and especially cancer induced by tobacco. And if you don't believe the concerns, look at the numbers here. By 2020, cancer could kill 10 million people per year with 16 million new cases per year and much of this being preventable but not unless we do something to change the trends.

A very interesting one and one that I think most people had not heard as much about but now is really emerging as an exciting opportunity for intervention is the indoor air pollution created by cookstoves, which has an astounding level of morbidity and mortality. Estimated 1 in 0.9 million deaths per year, more than for malaria, caused by the inhalation of particulates from indoor cookstoves. And this is particularly hitting those vulnerable who are in that setting a lot of the time, which is women and children.

The damage to the economy, the environment from the way in which this plays out, the risks that are attached to this to women who have to oftentimes trek long distances to collect firewood to support this indoor air pollution producing cooking is almost immeasurable. And yet, we have a chance to do something about this with a lot of the new technology that could be substituted that provides an opportunity for clean and cheap cooking in many of these settings.

But this is a real challenge to figure out how to do this effectively recognizing that cultural practices that have been in place, in some instance for centuries, suggest that this is the way that families should be preparing food and to change that requires really rigorous research efforts to understand what it -- what it takes to encourage adoption in communities that could be greatly benefited but wouldnít necessarily see it that way without an effective program to do so. And we're certainly interested in that possibility.

The Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves is this international public-private partnership between U.N. Foundation, government agencies, academic institutions, companies, non-profits. Secretary Hillary Clinton has been very engaged in speaking out about the importance of this and setting a very ambitious goal which is efficient, clean cookstoves in 100 million homes by 2020. That will really stress all of us to make that happen, but it does seem to be achievable.

Another example where non-communicable diseases need our attention and where there are research results to suggest that this is a -- an approachable problem with an appropriate set of thoughtful resources is the global burden of infant mortality. It is frightening to contemplate 3.6 million infants dying annually during the first 28 days of life, most of these in developing countries, many of these preventable.

NICHD, the child health institute at NIH, has been training as a research program midwives in Zambia using just an essential newborn care course that teaches them about simple things like birth asphyxia and avoiding infections in the early neo-natal stages. And as a result, all cause -- seven-day neonatal mortality in Zambia dropped almost in half as a result of having the availability of these midwives to do this kind of care and not care that requires lots of sophistication or expense to establish. Total cost of the program, $20,000; per life saved, $208. Not a bad deal. Obviously, a small program but one you could contemplate expanding to great benefit. And that's published in the -- Pediatrics if you want to see more of the details.

Let me come to the fourth of the four topics which is now to step us back from specific kinds of diseases as targets and talk about the whole need for networks that can empower the capacity of developing countries to play a larger role in this kind of research because I think we would all agree going forward the idea that the research can be done by individuals in-country with the resources and the skills to do so is a vastly better one than having this kind of capability only exercised on behalf of those countries by others outside.

So what to do? I want to tell you about two programs; one of which is not quite started and one of which is but which we are excited about as a way of building this kind of capacity. In both instances, I'll be talking about Africa. The H3Africa program is again an effort to shift away from the practice in many research studies of removing samples from Africa and analyzing them elsewhere and to build the infrastructure to allow this research to occur on the continent. This is a partnership between NIH and the Wellcome Trust and with organizational support from the African Society of Human Genetics. The idea is to focus on both genetic and environmental risk factors for disease, both common disease that's not non-communicable and also infectious diseases.

And this is an effort to take the same kinds of approaches that are now being applied widely in higher income countries and see if they can be exported and implemented in a different setting recognizing that there's a lot of challenges here. That will mean setting up information technology networks for the participating institutions; phenotyping centers, biorepositories, and so on. But the promise here being able to uncover the causes of illnesses in the cradle of all of human civilization should be a very interesting and opportune one indeed.

And who knows what we might discover. I'm very taken by this interesting connection about how what we learn in one part of the world may shed light on another part in very unexpected ways. I donít know if you saw this paper from about a year ago. There's been this puzzle about why it is that African-Americans are much more likely to suffer from a particular kind of kidney disease, focal glomerulosclerosis, which often goes on to kidney failure and the need for dialysis. So why is the frequency so high?

By carrying out a study across the genome, it turns out that variations in the APOL1 gene are responsible for that heightened risk. So why would African-Americans have that high risk version? Well, guess what. That same variation that places the risk of kidney disease in the developed world, it protects against sleeping sickness in Africa. And so that is probably why those variations have risen to a higher frequency in a population where sleeping sickness was a major challenge for that group to survive. So it's evolution in action here but again showing you that genetic variation shouldn't be thought of as, well, beneficial or not beneficial. It depends on the setting.

The other project I want to tell you about which is now underway but just, that we also expect will provide real opportunities for building capacity in Africa is about both medical education because we all understand how much we need more healthcare providers in Africa. But it's also intended as a means of supporting better capacity in research and hence NIH's interest in joining onto a project which is funded by ourselves in a modest way and by PEPFAR in a much more significant way. So this is a joint effort between our institutions described in this paper in Science back in December. I had the pleasure of going to the organizational meeting of this program in March, which was held in Johannesburg, and learning more about the way in which these educators are going to work together to try to deal with what is clearly a major problem in terms of capacity.

I suspect many of you have found the Worldmapper site that portrays in very dramatic ways in a visual fashion of what's going on across the world depending on what parameter you're looking at. And this is, for me, I think a particularly strong representation of the problem that we're trying to solve with MEPI, the Medical Education Partnership Initiative, in terms of building capacity and the ability to provide more health. This is the land mass, the familiar picture of what the world's countries look like. And imagine what would happen then if you took that picture and tried to portray some other feature.

So for instance, HIV-AIDS. And if you were to put that on the map and basically distort the countries by the number of cases present in those places, what would it look like? That is the dramatic result that you see there. And you see the incredible burden faced by Africa and increasingly also by India as you can see with many other parts of the world shrinking a bit just because their incidence is relatively lower but certainly not to be ignored either.

If you do that same approach and ask, okay, where are the physicians. Again, very troubling that you see areas where there are lots and lots of caregivers. And then here is Africa; this is South Africa the -- this pink tip here and most of the rest of Africa clearly very underserved by the availability of healthcare providers, one of the things that MEPI hopes to address.

And if you ask about scientific capabilities, you can simply look at publications. And again you see a very large representation from Europe and the U.S. and Japan and increasingly from China and India. But look at Africa, very much now not being able because of the lack of trained individuals and other resources to contribute. We want to change that. And MEPI aims in a rather bold way to try to provide the opportunity to do that kind of training.

At that meeting in Johannesburg, it was inspiring to walk around the room and talk to the leaders from these institutions. Twelve countries, 30 institutions, most of them dedicated to the idea of medical education, many of them saying they've never been in the same room together before because while they had partnerships of a north-south sort, they had not really been invited to have the south-south partnership that MEPI represents.

Here are the countries involved in the Medical Education Partnership Initiative at least initially. And all of them have significant institutions that are joining up in this effort with support from PEPFAR and NIH. And we're really excited to see how this whole enterprise will come together.

So in a few somewhat brief minutes but hopefully not too long so that we can still have some discussion, I've tried to tap into areas that NIH is supporting in these four particular topics. There's no doubt much more that could be said about global health research. Again, I just want to emphasize how from our perspective, this is a major area of opportunity and interest and one that we hope to be contributing to.

But we can only do so in a fashion that partners up with other international organizations and particularly with the private sector in order to bring things through all the way to a successful marketing and conclusion. And that is a very good reason to have this session here to today. And I want to thank the organizers, BIO Ventures for Global Health, in inviting me and bringing us all here together this afternoon.

Thank you very much.

1 http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/magazine/frenkqa/

Page Updated: 1/5/24

U.S Copyright Status: This text = Property of AmericanRhetoric.com. Image (Screenshot) = Fair Use.