|

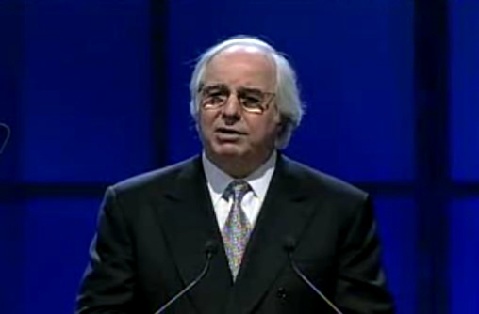

Frank Abagnale National Automobile Dealers Association Convention Address delivered 12 February 2006, Orlando, FL

[AUTHENTICITY CERTIFIED: Text version below transcribed directly from audio] [Good] morning, it's my pleasure to be here this morning. [I've] been asked to talk a little bit this morning about my life. About 35 years ago, a veteran police journalist¹ wrote a book about my life. He was a great storyteller and, of course, like all storytellers he told a story from his point of view. About 30 years later, what some consider to be the world's greatest film director decided to make a movie about my life, and like great movie directors, he decided to tell you a story from his point of view. This morning, I thought I'd tell you the story from my point of view. I was raised just north of New York City in West Chester County, New York, in a little town there called Bronxville. I was actually one of four children in the family -- the so-called middle child of the four. I was educated by the Christian Brothers of Ireland at a private Catholic school called Iona, in New Rochelle, New York, where I went to school from kindergarten to high school. By the time I had reached the age of 16, in the 10th grade, my parents, after 22 years of marriage, one day decided to get a divorce. Unlike most divorces, where the children were usually the first to know, my parents were very good about keeping that a secret. I remember being in the 10th grade when the Father walked into classroom one day and had the Brother excuse me from class. When I walked out in the hallway, he handed me my books and told me that one of the Brothers would drive me to the county seat in White Plains, New York, where I would meet my parents and they would explain what was going on. I remember that Brother dropped me up the steps of a stone building and told me to climb on up the steps and my parents would be waiting for me in the lobby. Walking up the steps I noticed a sign that said "Family Court" -- but really didn't understand what that meant. When I arrived in the lobby my parents were not there, but I was ushered into the back of an immense court room, where my parents were standing before a judge. The judge eventually saw me back at the room and he approached me to -- to come up to the bench. I walked up and stood in between my parents. I remember distinctly that the judge never looked at me, never acknowledged that I was standing there, never lifted up from his papers. He simply said that my parents were getting a divorce, and because I was 16 years of age I would need to tell the court which parent I would choose to live with. I started to cry, so I turned around and ran out of the courtroom. The judge called for a 10 minute recess. By the time my parents got outside I was gone. My mother never saw me again for about seven years, 'til I was a young adult. My father, contrary to the movie, never saw me nor ever spoke to me again. In the mid 1960s, running away was a very popular thing for young people. A lot of them got caught up in Haight-Ashbury -- the hippie scene, the drug scene. Instead, I too a few belongings from my home, packed them in a bag, boarded what was then the New Haven and Hartford Railroad for the short train ride down to Grand Central Terminal in New York. My father did own a stationary store, actually in Manhattan, on the corner of 40th and Madison -- still there today -- and like all of us we had to work in that store, so I made deliveries for my dad from the time I was about 14. I knew the city very well, so I started looking for the same type of work. There were a lot of signs in the windows: "stock boy," "delivery boy." I'd walk in and apply: "So tell me, young man, how old are you?" I was 16. "How far did you go in high school?" 10th grade. "I'll hire you." And I went to work for a small amount of money, but I soon realized that I could not support myself on that amount of money. I also realized that as long as people believed I was 16 years old, they weren't going to pay me any more money. At 16, I was six foot tall. I've always had a little gray hair since I was about 15. My friends in school said that -- once a week we wore a suit -- I looked more like a teacher than a student. So I decided to lie about my age. In New York, we had a driver's license at 16. Back then they didn't have a picture on them. It was just an IBM card, so I altered one digit of my date of birth. I was actually born in April 1948, but I dropped the "4" -- converted it to a "3," and that made me 10 years older -- or 26 years old. I walked around applying for the same type of work. People gave me a little more money, a few more hours, but even then it was difficult to make ends meet. On of the few things I had taken when I left home was a checkbook. My father had opened a checking account for me at a small community bank in Mount Vernon, New York. I had a little money in the account, so every so often I would write a check to supplement my income -- 10 dollars, 15 dollars. The funds were there. The checks were good. It was my friends, my peers who would say to me, "You know, you're the only guy I know [who] walks into a bank in the middle of Manhattan. You have no account there. You don't know a soul. You go talk to somebody behind a desk, and they 'okay' your check." "Oh, well, my checks are good." "If walked in that bank they wouldn't touch my check. You walk in; they don't bat an eye." Years later, reporters would say that that was my upbringing -- mannerisms, dress, appearance, speech. Whatever it was, it was very easy to do, so consequently, when the money ran out, I kept writing those checks. [Of] course the checks started to bounce. [The] police were looking for me as a runaway, so I thought maybe it was a good time to start thinking about leaving New York City. But I was quite apprehensive about going to Chicago, Miami. [I] wondered if they'd cash a New York check on a New York driver's license as quickly as they did in Manhattan. I was walking up 42nd street one afternoon about five o'clock in the evening, 16 years old, pondering all of these things, when I started to approach the front door of an old hotel that used to be there called the "Commodore Hotel" -- now the Grand Hyatt. Just as I was about to get to the front door of the hotel, out stepped an Eastern Airline[s] flight crew onto the sidewalk. [I] couldn't help but notice the captain, the co-pilot, the flight engineer, about three or four flight attendants -- all boarding a van to take them to the airport. As they loaded the van, I thought to myself, "That's it. If I could pose as a pilot, I could travel all over the world for free. I could probably get just about anybody, anywhere to cash a check for me." So, I walked up the street a little further to 42nd and Park. I went to cross over, but I heard a huge helicopter and looked up and there was New York Airways landing on the roof of the Pan Am building -- Pan Am, the nation's flag carrier, the airline that flew around the world. I thought, "What a perfect airline to use." So the next day I placed a phone call to the executive corporate offices of Pan Am. When the switchboard was ringing, I had absolutely no idea what I was going to say. When they answered, "Pan American Airlines -- good morning, can I help you?" "Uh, yes, ma'am. I'd like to speak to somebody in the um...somebody in the purchasing department." "Purchasing? One moment." And the clerk came on and I said:

And he came back and said, "My supervisor says you need to go down to the "Well Built Uniform Company" on 5th Avenue. They're our supplier. I'll call them and let them know you're on the way. They'll take care of you." Well, that's exactly what I wanted to know, so I went down to the "Well Built Uniform Company." A little fellow named Mr. Rosen fitted me out in a uniform. Back then they were black gabardine; the three gold stripes on the arm, the gray hair -- I certainly looked old enough to be the pilot. When he was all done I said:

New York had two airports. LaGuardia and Kennedy. LaGuardia was about 20 minutes from Manhattan; Kennedy was about 50. So naturally, LaGuardia being the closer of the two, that’s where I went. I spent most of the morning walking around in the uniform trying to figure out now that I had this uniform, “How the hell do you get on these planes?” Well, I got a little hungry about lunchtime so I walked in the luncheonette, sat down at the counter on the stool, and ordered a sandwich. Moments later, a TWA crew walked in. [The] flight attendant sat in the booth, pilots up at the counter on either side of me, [the] captain right next to me. Now back before deregulation of the airlines, airline people thought of themselves as just one big family. They didn’t hesitate a moment to talk to each other, so the captain kind of leaned over:

Well, I picked up on that right away.

Now airline people have a lot of jargon for things and one of them is they never call a plane a "plane" or an "aircraft." They call it "equipment" -- and "What type of equipment" you're on meant "What type of plane do you fly?" Back then a DC-8, a 707. Course I didn’t know that and I thought, "What type of equipment am I on?" The only equipment I'm on is this stool. They must mean what type of equipment is on the planes that I fly. So I thought, well, they’ve got the wings and they’ve got the engine. And they always had a sticker on the engine (who manufactured the engine). So I said "Yes, General Electric." All three pilots kind of just stopped eating and leaned over. Captain said, "Oh really? What do you fly, a washing machine?" So I knew I said the wrong thing. Out the door I went. Everybody had an airline ID card, plastic laminated card much like a driver’s license today. Yet, without the ID card, the uniform was worthless. I went back to Manhattan pretty discouraged thinking, “Where would I come up with a Pan American Airline Corporate ID?” I was sitting in the hotel room. I noticed the big thick Manhattan Yellow Pages on the dresser, so I flipped them open and came to the word "Identification." There were three or four pages of companies who made convention badges, metal badges, police badges. [I] started to call around and finally one company said, “Listen, most of those airline IDs are manufactured by Polaroid 3M Company; [you] need to call one of them.” [I] finally got the 3M Company on the phone in Manhattan. “Yeah we manufacture Pan Am’s identification system along with a number of other carriers. How come?” I said, “I tell you, I’m a purchasing officer for a major U.S. carrier. I’m in New York just for the day. We're getting ready to expand our routes, hire a lot of new employees, go to a formal ID. We're very impressed with this Pan Am format -- wondered if I came by your office this afternoon briefly, we could discuss quantity and price.” “By all means, come on by.” So I went by dressed in a suit. The sales rep opened the book, “Here you go. We do United, Delta, Eastern, Pan Am, right here.” “Yeah, we like this Pan Am format -- wondered if you have a sample I could bring back.” “Sure, I’ll be right back.” And he brought me back a five by seven glossy piece of paper with a picture of an ID card blown up in the middle of it, someone else's picture in the picture, John Doe for a name and in bold, red ink across the front: “This is a sample only.” I said, “No, I’m afraid this won’t do. You know, I need to bring back an actual, physical card. By the way, what is all this equipment on the floor?” “Oh, now we don’t just sell these cards. We sell the system -- camera, laminator....” I said, “We’d have to buy all this.” “Absolutely.” “Well, tell you what, since we have to buy it all, why don’t you just demonstrate how it works and use me?” “Fine, have a seat right here.” [He] took my picture, made up the card, and out the door I went. I was going down the elevator studying the card. It had a blue border across the top, about a quarter of an inch in Pan Am’s color blue, but not a single thing on the card said Pan Am. No logo, no insignia, no name. This was a plastic card like a credit card. You couldn’t type on it, couldn’t write on it, couldn’t print on it. Discouraged, I put it in my pocket, headed back to the hotel. As I was walking back, I noticed I had passed a hobby shop. So I turned around and walked back.

Pan Am says they estimate that between the ages of 16 and 18 years old, that I flew well over a million miles for free, boarded more than 250 aircraft, visited more than 26 countries. Pan Am says keep in mind that though Frank Abagnale did in fact pose as one of our pilots, he never once stepped on board one of our aircraft. That’s true. I never flew on Pan Am because I was afraid someone might say to me, “You know, I’m based in San Francisco. I’ve been out there 28 years. I don’t recall ever meeting you before.” Or someone might say, “You know, your ID card is not exactly like my ID card.” So instead, I flew on everyone else. If I wanted to go somewhere, I literally just walked out to the airport and looked up on the board: United Flight 800 to Chicago. Then I went downstairs to the door marked "United Operations" and walked in. The operations clerk:

And I’d give them my ID; he’d write me out a pass; I’d walk out -- hand it to the flight attendant; she’d open the door to the cockpit and I’d step in. There you had a captain, co-pilot, flight engineer, and the seat behind the captain called the "jump seat" where pilots "dead-head" on company time. Now because pilots loved to talk shop, once you picked up that jargon, [it] was the same conversation over and over and over:

On the taxi out, always the same question:

I had that one down perfect. Matter of fact, whatever they flew, I didn’t fly. So I had no problems with that. And when we’d arrive in Chicago, I’d get off the plane, go by the Pan Am ticket counter, but just enough to get the attention of the passenger service rep.

I’d go down to the Palmer House Hilton and walk in and on the corner of the registration desk there was a little sign that said: "Airline Crews." That was a three-ring binder you signed in, reference your flight number, showed your ID card; they gave you a key. I’d stay two or three days. Pan Am would be direct-`billed for my room and my meals. I also could cash a check at the front desk, usually up to a hundred dollars because I was an employee of the airline. The airline had a contract with the hotel and as a courtesy they’d cash your check. But then I found out that every airline honors every other airline employee’s personal check, a reciprocal agreement still practiced today in 2006. So at the Orlando airport this afternoon, a Delta flight attendant can walk up to the American ticket counter, show her Delta ID, and cash a personal check up to a hundred dollars and visa versa. [Of] course when I found that out, I’d go out to JFK or LAX only I’d go to everybody -- Northeast, National, KLM, Air Fran[ce]. It would take me a good eight hours stopping at every counter and every building. By the time I got all the way around the other end of the airport at least eight hours had gone by. What do you have in eight hours? Shift change, new people. So I’d go all the way back around the other way again.

I made a great deal of money. The only reason I quit at 18 is the FBI issued a John Doe warrant for interstate transportation of fraudulent checks, a federal offense. The John Doe warrant meant the FBI didn’t know my identity. In the warrant, the FBI said, based on interviews with people I had contact with, I was approximately 30 years old. I was 18. [I] had a great deal of money so I hung the uniform up and moved to Atlanta, Georgia. In Atlanta I moved into a very swank singles complex that had just been built there called the Riverbend Apartments. On the application for the lease there were many questions. One of them was occupation. I began to write down airline pilot, but the next question said "Employed by," "Supervisor’s Name," "Telephone Contact." I thought to myself, "I’ll need to come up with something that would be impossible to check out, yet something that would justify why I drive an expensive car, wear expensive clothes, don’t work much." So I wrote down the word “doctor.” [It was the first thing came to my mind, nothing else. But I had a very inquisitive apartment manager,

And I figured being a singles complex, "pediatrician" would be pretty safe. So I moved in “Dr. Frank Williams, pediatrician.” Everybody called me “Doc”, always a typical question --

One of the girls came by, I always gave them a thorough examination and sent them on their way. I was young, but not stupid. I was living there for about two or three months. Everything was going great. One afternoon there was a knock on the door, very distinguished gentleman, mid 50s standing there.

Dr. Gordon was going through a divorce, just separated from his wife who was very upset, very lonely, loved to talk every day on the way to the car, out to the pool, he’d stop you. After a minute or two about the weather, he’d start to speak in medical terminology. Obviously I couldn’t converse with him so I in turn would cut him short. Eventually, I knew he’d get suspicious. So, determined not to move, every day I went to Emory University’s Medical Library. Every day I read the daily journals from Johns Hopkins, from the Mayo Clinic. Every day I would take a certain part of the journal, memorize it, and every night when Dr. Gordon pulled in his parking slot, I was sitting on his doorstep. Literally, every night. “Hey Doc, hear about this new theory they are using up at Mayo?” “What is it tonight?” And I’d follow him into his apartment. I knew he was aggravated. If he’d go in his bedroom, sit on the bed, I’d go in his bedroom, sit on the corner of the bed. If he’d go in the kitchen, I’d follow him back and forth. [If he’d] go to the bathroom I’d talk through the door. Pretty soon he’d come home, “Hey Doc --”. “I don’t have time to talk to you right now. I got to go.” The guy started to avoid me, which is exactly what I wanted. One afternoon I received a phone call from the hospital administrator who is not a physician, but the administrator of the hospital -- “Dr. Gordon suggested I give you a call. He said you’d be more than happy to help us out.”

I did pass the bar in the state of Louisiana, not in two weeks as the movie implied, but in eight weeks. Louisiana at the time did not require a law degree to take the bar. Louisiana, of course, practices their law under the French Napoleonic criminal code of procedure, as they did then and do today. I took the bar; passed the bar. I went to work for then Attorney General P.F. Gremillion in the Civil Division of the state court where I practiced law there for almost a year before -- on my own -- I resigned and left. A lot of people say, "You know, it’s not so much the people you impersonated as a teenage boy as it is the crimes you perpetrated as a teenage boy." Well, I did a lot of things that had just never been done before, so they got a lot of attention. I was walking down a Chicago street one day counting five twenty dollar bills I had in my pocket. As I was counting them, I noticed I had passed the front door of a bank. There was a sign on the window [that] said “Open A Checking Account”. So I thought to myself, "I’ll go in this bank and I’ll open a checking account with this hundred dollars. I’ll give them this phony Pan Am ID for identification. In two weeks, they’ll mail me 200 printed checks in a box with this name and with this ID -- I’ll cash them anywhere." So I walked in and opened the account. New Accounts person came back said, “Here’s the receipt for your deposit. These are some temporary checks and we’ll be mailing you your printed checks in about ten days.” Now being young, I was always inquisitive,

So I walked over and took a big stack of them off of the shelf. Nobody cared. [I] went back to my hotel -- couldn’t sleep. [I] woke up the next morning and bought what was called a "Burroughs [ph] 1000 Magnetic Encoder." It looked like a big green calculating machine, and I magnetically encoded my account number the bank had assigned to me the day before on the bottom of every one of these blanks. I then went back to the bank, put them on the shelf in the lobby, and everyone who came in put their check in my account. I was at the Logan Airport in Boston. I was trying to catch a flight. It was about a quarter to twelve at night. I ran out to the airport. The whole airport was closing down: rent-a-cars, gift shops, ticket counters. I walked up to the ticket counter, “Excuse me, you’re closing the airport?” “Actually, the airport lies in the heart of the city. [It] comes under the government’s noise abatement control program. We shut down all jet operations at midnight. Next flight out is at six- thirty in the morning.” So, I sat down wondering what to do. I noticed they were all sticking their cash and receipts in these big bank bags. Then they’d zip them close, lock them, put them under their arm, walk around the counter and down the hall to the bank that was in the terminal. They’d stick their key in the night box, open it, drop the bag down the chute, make sure it went all the way down, closed it, locked it -- one right after the other: Hertz, Avis, Delta, Eastern, [unintelligible], dropping the bag. Well, I didn’t give this a lot of thought, but I came back to the airport the next night about a quarter to twelve. I had rented a bank guard uniform from a costume store in Boston. I hung a beautiful sign over the night box [that] said: "Night Box Out of Order -- Please Leave All Deposits with Guard on Duty." Everyone did. I was the nervous one sitting there going, "How in the hell can a box be 'out of order?'" I mean that’s like a mailbox with an out of order sign. Of course like any criminal sooner or later you get caught, and I was no exception to that rule. I was arrested just once in my life, when I was about to turn 21, by the French police in a small town in southern France called Montpellier. [The] French police taking me into custody actually on a Interpol warrant issued by the Swedish police. When the French authorities arrested me, they realized I had forged checks in their country, so they refused to honor the extradition and the warrant for my arrest. They later convicted me of forgery and sent me to French prison. I served my time in a place a called the Maison D'arrêt (the "House of Arrest”) in a small town in southern France called Perpignan. It was extremely important to Steven Spielberg to go back to that prison -- as he put it, to "the exact cell" I was in and to recreate it according the log books during my stay there. I went -- entered the prison according to Mr. Spielberg’s log books at 198 pounds, left the prison at 109 pounds. Bread and water for breakfast, bread and soup for lunch, bread and coffee for dinner. No electricity, no plumbing, no furniture -- just a blanket on a floor with a hole in the floor to go to the bathroom. When I left the prison I was extradited to Sweden where I was later convicted of forgery in a Swedish court of law and sent to a Swedish penitentiary in Malmö, Sweden, where I served a prison term. When my sentence was over, U.S. federal authorities returned me to the United States. [I was] arraigned in U.S. Federal Court. Eventually a United States federal judge sentenced me to 12 years in federal prison. I served four of the 12 years in a federal prison in Virginia. When I was 26 years old, the government came to prison and offered to take me out of prison on the condition that I go to work with an agency of the federal government for the remainder of my sentence -- until my parole had been completed. I agreed and was released. This year I am celebrating 31 years with the FBI. I have worked for the Bureau now for over 31 years. Today I teach at the FBI academy in Quantico, Virginia, and spend most of my time -- four days a week -- out in our field offices throughout the United States. During my career at the Bureau and working for the government I have developed technologies used by 78 percent of the banks in the world today, and by more than 91 percent of the governments around the world to protect their passports, car titles, birth certificates, identifications, negotiable instruments, stocks, bonds, etcetera. And those technologies that I have developed along with companies like Novell, Computer Associates, Unisys, Standard Register of Ohio, and my business partners over the years have earned me millions of dollars in royalties and patents for those technologies which are used today by thousands of companies, corporations, and financial institutions.

But in the end we were extremely blessed that it was Steven Spielberg who went out of his way to make that film and out of his way not to glorify what I did, but to simply tell a story. He would tell Barbara Walters that "I immortalized Frank Abagnale on film, not because of what he did 40 years ago as a teenage boy, but because what he’s done for his country these past 31 years. That is why I made 'Catch Me if you Can' into a film." And in the end my family and I were very blessed and very pleased that he went out of his way, not to glorify the things I did, but to just tell a story. Carl Hanratty (Tom Hanks’s character) and I have remained friends for over 30 years. [I'm] godfather to one of his daughters. I worked directly under his supervision for 10 years. [He's been] like a father to me. He and I remained friends for over 30 years, until his death just six months ago at the age of 87. He was on the set during the filming of the movie, along with the two younger agents during the filming of the movie. As Steven Spielberg said, he was "telling a story about their story of chasing me." And in the end he had the opportunity to do that, and of course he’s a man who I loved, admired, and respected a great deal. I have been married for over 30 years. I make my home in Tulsa. I’ve raised three sons there, as I have mentioned. My youngest boy is a senior at the University of Kansas, where he'll graduate in May -- where his older brother did his undergraduate studies. I have a son in a graduate program at the University of Nevada in Las Vegas, where he’ll graduate this year; and my oldest boy, 26, who graduated from Loyola School of Law in Chicago -- and I am very proud to say an FBI agent in Washington, D.C. I obviously get a lot of emails from the film still today from people as young as eight to people as old as 80. People write and just make comments. Some people write and say, "Well, you know, you were brilliant." "You were a genius." I was neither. I was just 16 years old. Had I been brilliant, had I been a genius, I don’t think I would have found it necessary to break the law in order just to survive. I know that people are fascinated by what I did as a teenager but what I did was immoral, illegal, unethical, and something that I am not proud of -- nor will I ever be proud of. Many people write and say, "Well, you were certainly gifted." That I was. I was one of those few children -- very few -- who got to grow up in the world with a daddy. The world is full of fathers but there are very few daddies -- and any child who's had a daddy is an extremely gifted child. I had a daddy who loved his children more than he loved life itself. Steven Spielberg would later write “the more I researched Frank’s youth, the more I couldn’t help but put is father in the film through the likes of Christopher Walken. My father was a man, who, every day of your life, told you he loved you, literally, not only by the spoken word but by sheer physical affection. 6 foot 3, every night at bed time, three boys and a girl, he was in your room. He would drop down on his knees to come down to your bedside, kiss you on the cheek, pull the cover up, and he’d put his lip up on your ear lobe and whisper in your ear "I love you. I love you very much." He never missed a night. As I grew older I sometimes fell asleep before he got home, but I always woke up the next morning -- knew he had been by my bed. Years later my older brother went in the Marines. He was 6 foot 4, played semi-pro for Buffalo, but when he’d come on leave my father would walk around to his bed, hug him, kiss him -- told him he loved him. When I was 16 years old I was just a child. All 16-year-olds are just children. And like all children I needed my mother and I needed my father. All children need their mother and their father. All children are entitled to their mother and their father. And though it is not popular to say so, divorce is a very devastating thing for a child to deal with, and then have to deal with the rest of their natural life. For me, a complete stranger told me I had to choose one parent over the other parent. I’ve never made that choice. It was a lot easier to turn and run. How can I tell you my life was glamorous? I cried myself to sleep 'til I was 19 years old. I spent every birthday, Christmas, Mother’s Day, Father’s Day in a hotel room somewhere in the world where people didn’t speak my language, associating with people who believed me to be 15 years older than I actually was. I never got to go to a senior prom, high school football game, or even share a relationship with someone my own age. I always knew I’d get caught. Only a fool would believe that you can continually break the law and not get caught. The law sometimes sleeps, but the law never dies. It was just a matter of time. I was caught, I went to some very bad places. My boys have grown up asking their mother, "Why is it that dad wakes up in the middle of the night and goes down to [the] TV room, 'cause he doesn’t turn the TV -- he just sits there all night?" Because there are things you can’t forget, things you're not meant to forget. While I was sitting in that French cell, my father, 57, extremely physical, athletic man, climbing the subway steps in New York as he did every day, just happened to trip on a step, reached his arm out to break his fall, slipped again, hit his head on the rail, rolled to the bottom of the step, he was dead. I didn’t know he was dead. I was sitting in that pitch black cell. But I was thinking about him -- how much I loved him, how much I missed him, how much I couldn’t wait to see him, hold him, hug him, kiss him -- and tell him how sorry I was. But I never got the opportunity to do that. I was grateful that I was brought up in a great country which gives everybody a second chance. I owe my country 800 times more than I could ever repay it for the opportunities it's given me these past 30 years. That is why I’m at the FBI 26 years beyond my legal obligation to do so -- just simply returning a debt that I will never be able to actually fully return. I was very fortunate that 31 years ago on an undercover assignment in Houston, Texas, I met my wife. When the assignment was over, I broke protocol to tell her who I was. Not a dime to my name, I eventually asked her to marry me. Against the wishes of her parents, she did. Now I could tell you that I was a born-again Christian. I could tell you that prison rehabilitated me. I could tell you that I was a kid who made some mistakes and grew up. But the truth is, God gave me a wife; she gave me three beautiful children, and in doing so she gave me a family. She changed my life: she and she alone. Everything I have, everything I’ve achieved, who I am today, is because the love of a woman and the respect three boys have for their father, something I would never, ever jeopardize. There comes a time in all of our lifetimes we grow older and we have children. And as every parent in this room knows, whether your child is 6 months or 60 years old, when you lay your head down on a pillow at night and you begin to close your eyes, they’re the last thing you see, the last thing you think about. So if you still have your mother, you still have your father, you give them a hug, you give them a kiss. And remember no matter what kind of relationship you had with your parents, you will miss them when they're gone. And to those men in the audience, obviously very successful men, I would remind you what it is to truly be a man. It has absolutely nothing to do with money, achievements, skills, professions, degrees, accomplishments. A real man loves his wife. A real man is faithful to his wife. And a real man, next to God and his country, put[s] his wife and his children as the most important thing in his life. Steven Spielberg made a wonderful movie, but the truth is I’ve done nothing greater, nothing more rewarding, nothing more worthwhile, nothing has brought me more peace, more joy, more happiness, more content in my life than simply being a good husband, a good father, and what I strive to be everyday of my life, a great daddy. It’s been a pleasure. God Bless and thank you. 1Stan Redding Audio & Image #1 (Screenshot) Source: YouTube.com Page Updated: 10/12/21 U.S. Copyright Status: Text and Audio = Restricted, seek permission. Images = Fair Use. |

|

|

© Copyright 2001-Present. |

And I bought a model of a Pan Am 707

cargo jet for about two dollars and forty cents, took it back to my room, opened

the box, threw all the parts out, but there at the bottom of the box was a sheet

of decals that went on the plastic model, and the little Pan Am logo that would

have went on the tail of the plastic plane went up perfect at the top of the

plastic card. And the word “Pan Am” in the special styling of graphics that would

have went on the fusil lodge went perfect across the top of the card and the

clear decal on the laminated plastic made a beautiful identification card.

And I bought a model of a Pan Am 707

cargo jet for about two dollars and forty cents, took it back to my room, opened

the box, threw all the parts out, but there at the bottom of the box was a sheet

of decals that went on the plastic model, and the little Pan Am logo that would

have went on the tail of the plastic plane went up perfect at the top of the

plastic card. And the word “Pan Am” in the special styling of graphics that would

have went on the fusil lodge went perfect across the top of the card and the

clear decal on the laminated plastic made a beautiful identification card.