[AUTHENTICITY CERTIFIED: Text version below transcribed directly from audio]

Thank you. Thank you very, very much, everybody.

Thank you, Ben, for an extraordinary introduction. I'll have to find some way to bottle that one, and I'm enormously appreciative of it and I'm humbled by it. And it's good to have a good friend like Ben Barnes. I will tell you, anyone in politics in Austin during the 1960s knew about Ben, who had barely started shaving before he was elected to the Texas House of Representatives. And then he went on, as Greg said, to become the speaker and later the lieutenant governor. But now he continues his service at the LBJ Foundation. And Ben, wherever you are now, Ben, thank you so much for being a terrific friend of so many people in public service and for your continued contributions. Much appreciated.

I want to thank -- I want to thank Greg for the welcome to the University of Texas, to UT. He mentioned in his introduction the time we were able to spend over the Pickles Research Center. What an extraordinary place, what extraordinary people. And what really struck me this morning was that while Texas is obviously so well known as the oil-producing part of America and has built its reputation on that for years, it really is now the energy-producing center of America. And what you are doing with respect to research on solar and wind, alternative, renewable, is exactly what President Obama and I and others hoped would happen in the context of our efforts on global climate change and the agreement we signed in Paris. The agreement, obviously, is not going to guarantee we meet a 2 degrees centigrade increase in temperature, but what it is going to do is send a message to the marketplace exciting the allocation of capital, exciting our next Thomas Edison or Bill Gates or Steve Jobs to find a way to have battery storage or some cheaper form of a solar cell, and that is the way we're going to solve this problem. And University of Texas is going to contribute to that significantly. So, Greg, thank you for what you're doing.

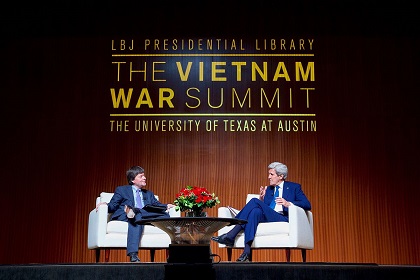

I want to add my voice to that of so many people here who I know beforehand have always -- have been praising what Ken Burns has done and his contributions to the study of history and the art of documentary film. I listened in the corner there to the conversation that was taking place. It was absolutely fascinating -- honest, which is important, on this topic. And I thought immediately that what I need to do is not give some long, quote, "keynote" address as it is billed, but just try to share a few quick observations with you, and then have the time to be able to have Ken grill me and we can have a good conversation. And I think that might be a little bit more productive and rewarding for everybody.

But his unbelievable accomplishments on Brooklyn Bridge, the conservation of our National Parks, the epic narrative of the Civil War, his new -- his latest film on Jackie Robinson, his film on baseball -- this guy really taps into the pulse of our nation and has a way of presenting it that is just absolutely sheer delight -- subtle, brilliant, honest. And I am absolutely more than confident that the extraordinary time and the passion that has consumed this particular project means the final product is not only going to be a work of art -- and you heard him; I mean, they're changing a word or two after it's locked -- it's going to be the definitive examination of Vietnam, with profound impact not only on the way that America thinks about that war, but I think on America's engagement with the issue of war itself. And I think it will do so for the better.

I know that this conference and tonight this topic, these couple of days, call for a serious analysis of what happened and why -- it's about history. But it's also about us, about our heart and soul and our gut; about how wrenching it was in the ways that Lynn and Ken just described to you. And this examination should help us to understand Santayana's famous warning to those who don't heed the lessons of the past. So I look forward when I finish to a good exchange, but to lay the groundwork for that conversation let me make a few key points that I think are key in the context of this conference that might not otherwise surface as we are principally looking backwards.

First, those who expressed concern about the way the war in Southeast Asia was conducted were, I think this film will show, clearly justified in those concerns. I am not going to dredge up all of the old arguments -- that is well-trodden ground by myself and by others, including I thought quite definitively by Neil Sheehan, whose book title sums it up. As I know we're going to be reminded by Ken's documentary, there were mistakes in leadership, mistakes in communication, mistakes in strategy. There were huge mistakes in the basic assumptions about the war. So it is not a surprise that public support virtually disappeared at a critical point of time. And we can talk about that a little bit.

My second point is that the confusion that some Americans showed in blaming the warriors for the war itself was tragically misplaced. Our veterans did not receive the welcome home. Our veterans did not receive either the welcome home nor the benefits nor the treatment that they not only deserved, but needed, and the fundamental contract between soldier and government simply was not honored. As a result, the vets themselves had to go out and fight a whole new round of battles. I know that well, as one of the four co-founders of the Vietnam Veterans of America. They had to fight to get an increase in the GI Bill; fight to deal with homelessness and trauma; fight to have the ultimate sacrifice of their buddies memorialized on America's National Mall. And I thank Jan Scruggs for his extraordinary leadership with respect to that.

So when we talk about Vietnam, to me, here is lesson number one: Whether a war is popular or unpopular, or it's not even what we call a war but a conflict, we must always -- always -- treat our returning vets with the dignity and the respect that they have earned by virtue of their service to our nation.

My third and final point is that we were right to work hard, and in some cases we still are working, to move forward from the pain and the division of the war to begin a process of healing both within our country and between the United States and Vietnam.

We were right to think about what had gone wrong and to enact laws that shed greater light on how our government goes about its business. We were right to take steps to help Amerasian children and to welcome the many thousands of Vietnamese refugees following the fall of Saigon. Our Supreme Court was right to uphold the publication of the Pentagon Papers, so that more of the truth about the war would be revealed. And we were right -- and we were right to pursue a full accounting of our fellow citizens who were missing or unaccounted for, even after our POWs returned to our shores.

Now, let me say a word, if I can, about this accounting. It's not a well-known story in America, but it should be. For those of us -- John McCain and myself particularly as we approach the issue of normalization with Vietnam -- the accounting for POW/MIA was absolutely a prerequisite and non-negotiable. But this process of accounting, frankly, tells you something not only about us as Americans and our keeping faith with those who fall in battle; it also tells you something quite remarkable about the extraordinary openness of the Vietnamese people, who helped us search for the remains of our fallen troops even as the vast majority of theirs -- a million strong probably -- would never be found. They allowed helicopters to land once again unannounced in hamlets that brought back bitter memories of the war itself, and I remember negotiating with them to permit us to do that because we had to have the element of surprise in order to prove to people they weren't moving people from where they were being kept.

But the Vietnamese did so because they wanted also to move beyond the war. They dug up their fields and let us into their homes, their "history houses," their jails. On more than one occasion, they guided us across what were actually minefields. And even today as I stand here, thanks to a process that was fully embraced by President George H.W. Bush, with whom I had the pleasure of visiting yesterday in Houston -- one of the greatest people in America -- and General Brent Scowcroft -- together we were able to engage in what has become, my friends, the single most significant, most comprehensive, most exhaustive accounting of the missing and dead in any war in the history of humankind. And I think the United States should be very proud of that.

Literally, we have people over there still today as we sit here working to complete that task of accountability. And I have to tell you, having flown in a Russian helicopter, which was an experience of holding your breath for hours, across Vietnam and landing in these places, I remember walking down 20 feet deep into a pit that had been dug by archeologists, because it was the crash site of a C-130, and literally looking at the wall of mud in which there was the detritus of the C-130 looking for the remains in order to bring them home and repatriate them. That is the depths and extent to which we currently go.

Now, to be clear -- and I want to emphasize this here today -- certainly for me, and I think for most veterans, whatever their feelings were about the war, about what happened in America around the war, the process of reconciliation and restoring diplomatic ties was not about forgetting. If we forget, we cease to learn. And the tragedy of what happened in Vietnam has to be a constant reminder of the capacity to make mistakes, the capacity to see things in the wrong lens, the capacity to miss the signals, and ultimately to miss the constant reminder of the horror and the suffering that war inflicts.

But neither should we become the prisoners of history.

And I want you just to think for a moment -- this is what I thought was a little different from where we'd be otherwise, and I will go, I'm sure, in the conversation with Ken. I want you to consider how far we have come since normalization.

Twenty years ago, there were fewer than 60,000 American visitors annually to Vietnam. Today, there are nearly half a million.

Twenty years ago, bilateral trade in goods with Vietnam was only $451 million. Today, it is more than $45 billion a year.

Twenty years ago, there were fewer than 800 Vietnamese students studying in the United States. Today, there are nearly 19,000. And I was very proud as a senator to join in creating with my friend Tom Vallely -- who is here, who was mentioned by Ken -- and others the Fulbright School that exists today in Ho Chi Minh City, the second-largest Fulbright program in the world. It was the largest for a period of time. And later this year, we will be moving ahead with the founding of the Fulbright University Vietnam, which will offer a world-class education and deepen the ties between our peoples. And I can tell you that a huge percentage of the current governing -- the Government of Vietnam have attended the Fulbright program or come over here to go to Harvard or to go to some university and share an education.

That is a small measure, those statistics, of a remarkable transformation.

And I can -- I'll tell you a story. I can remember during the war securing a short pass to get to then-Saigon and coming up from the Delta where we were stationed, and sitting on the top of the Rex Hotel in a momentary pause from all of the craziness, and I was looking out at the city at night watching these flares popping all around the city everywhere, and in the distance hearing bursts of gunfire and the occasional roar of a C-130 flying by, and occasionally, the burp of what we call Puff the Magic Dragon. It was surreal. An oasis of sorts, but still the very essence of a war zone. You go back there today, which I have done, same hotel, same rooftop, but completely different view -- a completely different nation. The traffic circle outside the Rex is filled with motorbikes, teeming with passengers and every form of commerce -- from chicken coops to air conditioners to computer monitors to smartphones.

Nobody's thinking about the war. In fact, most people -- the majority in Vietnam are too young to even remember it. It's a different era. And that calls for a wholly different relationship.

No one back in 1968, I can tell you, could have possibly imagined General Secretary Trong's visit to Washington last year or President Obama's planned visit to Vietnam next month, which I look forward to joining him in.

No one could have imagined the broad bilateral agenda that we have developed, including education, climate change, science, health, high-tech, the internet, and military-to-military cooperation.

And no one could have imagined the United States and Vietnam joining with 10 other nations to achieve a priceless opportunity on trade. The Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement represents nearly 40 percent of the entire world's GDP, and it will create jobs, enhance the environment, improve working conditions, and strengthen commercial ties from Hanoi to Tokyo to Santiago to Washington.

And to be sure, let me make it clear: The true measure of our partnership is not just whether our economies grow, but it is how they grow. And we are working very carefully on all of those issues with respect to freedom and human rights, and by the way, within the Trans-Pacific Partnership, Vietnam has accepted labor unions, the right to strike. So some of you may think we made a catastrophic mistake, but in fact their rights have been enhanced.

I have to tell you all, when I -- I never thought when I was patrolling the Mekong that nearly 50 years later, I would be involved in a plan to help save that river. But together with our partners in the Lower Mekong Initiative, we are working to improve Vietnam's resilience to the effects of climate change, which they are already feeling hugely in the entire Mekong Delta. And we are focusing our aid on clean energy and the development of sustainable infrastructure and ecosystem resource management.

We're also working together in the academic arena. The Institute of International Education, Arizona State University, Harvard Medical School, and the University of Hawaii all have partnerships with institutions in Vietnam, several involving participation by the private sector.

And two decades ago, when the United States and Vietnam did normalize relations, we might have been able to foresee that our countries would eventually cooperate on economic matters, but something far less predictable is now the new normal -- we are cooperating on security issues as well.

Now, there is -- and particularly, I might add, with respect to the South China Sea, but that's not all -- on many other issues of security, we are engaged in discussions and in actual programs. Now, as I say all of this, is everything where we want it to be? No. There's no question that our government and the government in Hanoi obviously continue to have differences. But the good news is that we talk about them frankly and regularly and often productively.

And for anybody who tunes in to what the original goal was with respect to our efforts in Vietnam, which were to protect the country from becoming communist, let me make it clear to you today that while it is authoritarian and a one-party system, it's anything but communist, because communism is an economic theory. And they are as market-oriented as any country I've ever seen, a raging capitalism -- what -- notwithstanding within the constraints of a one-party system that still, like the authoritarian model of China and others, tries to contain its population and move forward. History will determine whether or not that ever works out in the long run.

So it's clear today that the Vietnam that we are engaged with none of us could have imagined in the context of the discussion that is taking place here in the context of the war. And it's clear that Vietnam is reaching forward towards the globalized world of modernity, and millions of people in Vietnam are already freely expressing themselves on Facebook, and many thousands of Vietnamese workers are already freely associating to defend their interests -- even though sometimes risky. They are the ones asking their government to guarantee in law the freedoms that they are starting to exercise in practice. And we know that the more progress that occurs in those areas, the more likely it is that our bilateral relationship, which has already come an extraordinary distance, is going to be able to ultimately reach its full potential.

In 1971, when I testified against the war in Vietnam before the Senate, I spoke of the determination of veterans to undertake one last mission so that in 30 years, when our brothers went down the street without a leg or an arm and people asked why, we'd be able to say "Vietnam" and not mean a bitter memory, but mean instead the place where America turned, and where we helped it in the turning.

So it has been 45 years since that testimony, but it is clear that we have turned some very important corners. There are hard choices still to make for our relationship to reach its full potential, but now we can say definitively -- because so many Vietnamese and Americans themselves refuse to let our past define our future -- Vietnam, a former adversary, is now a partner with whom we have developed increasingly warm personal and national ties. That is our shared legacy, and it's one that I hope we will continue to strengthen in the years to come. Thank you.

![]()

Mr. Ken Burns: Mr. Secretary, this is an extraordinary honor for me to be at this conference and to have the opportunity to have a conversation with you. We have -- Lynn and I and our team have lived with you for many, many years. We came to you at the outset of the project and told you that we wouldn't interview you, but you would exist, as your colleague John McCain would, in the film, in the story, and you do. And it occurs to me, because your speech was so correctly addressed to the future, that we should dwell on the experience but briefly back in Vietnam. How does the war come back to your consciousness in those private moments?

Secretary Kerry: Well, mostly in the context of the current wars. I mean, we're struggling to end the war of absurdity in Syria, to end the war in Yemen -- we're making progress there -- to end the struggle of Libya and get a government to stand up, end a war in Afghanistan, prevent a war in North Korea, and prevent other major challenges of failing states or failed states. We are making great progress; we're working very closely with Nigeria to end the plague of Boko Haram there, and I believe we will. We are making progress in Somalia, pushing al-Shabaab back.

So we're really in a massive struggle against extremism in many parts of the world, and so I'm constantly confronting a plethora of AK-47s and rockets and artillery and whatever in too many places. So in many ways I'm still living with war as a reality, but I'm so pleased, obviously, to be in a place to try to be making a difference. To either end it or prevent it is a privilege, and I think the United States is doing great things, some of which are not well understood or articulated publicly. But we're making more progress than people think. We will defeat Daesh, no question in my mind, and if certain things are able to happen with Russia and other players in the region with respect to Assad, we could do it much sooner.

So that's the way it comes back, and obviously there are always reminders in terms -- I mean, I don't think any veteran will tell you there aren't moments where there's a flash of some memory or someone that you remember or something. I just lost one of my crew members a few weeks ago, and all my crew guys were in touch with me and back with them, and some of them that were just very, very moved by that. But it just really grabbed them, and I think that it stays with you.

Mr. Burns: We started asking questions even before the war ended. What should Americans have learned from the conflict in Southeast Asia, and to what extent have we in fact put those lessons into practice?

Secretary Kerry: Well, I was listening to your conversation earlier, and I have to agree with you that it depends on where you sit and who you are and where you start. People are going to take different lessons out of it, and some people, unfortunately, are frozen in a place where their minds are just not going to open up to -- and I think you mentioned something to that degree -- they're not going to be able to move beyond the place where they retreated to and found safety.

Mr. Burns: Right.

Secretary Kerry: So that's too bad, but there are people in that place. But I think that clearly the lesson I articulated, number one, is don't ever confuse the war with the warriors, particularly in a volunteer status where people are serving their country and trying to keep all of us safe and responding to the requests of leaders who are supposed to get it right.

Mr. Burns: Right.

Secretary Kerry: So that's number one. Number two, make sure that the flow of information is as open and free as it ought to be so everybody can make a judgment and invest in the decision. And obviously, with respect to the Iraq War, there are questions about that because of what we learned about the absence of weapons in a time where people were being told they are there. So I think that that still lives with us, and we need to, obviously, insist on that.

I think, thirdly, we need to -- as we define our exceptionalism, which I believe in very deeply --

Mr. Burns: Me too.

Secretary Kerry: -- but which I believe we have to manage more carefully in terms of how we talk about it and brandish it, because other people think they're exceptional too, and are. And I think that it's important for us to look at whatever country it is we're looking at -- and as I mentioned a moment ago, so many assumptions, fundamental assumptions were incorrect in Vietnam, because we could only see it through one certain lens. It was a particularly colored lens with respect to World War II, with respect to Korea -- whatever frustrations may have grown up out of that, by the way. And I think -- never talked about enough, but I've always thought about it -- because of the way we thought about the communist threat and the experience of Joe McCarthy and the scare tactics that took place with respect to communism and people's fear that they never wanted to be on the wrong side of making sure we were tough enough about that.

And therefore, when threats of the entire Asia domino theory were thrown at people, there was a bias towards accepting that notion rather than thinking about the history of Vietnam or the history of Ho Chi Minh or the history of their --

Mr. Burns: Seeing it as national liberation and not a proxy war.

Secretary Kerry: All of the above, and understanding the civil nature of it and so forth. So I think those three things are -- now, there are a lot more lessons, folks. You can take the Powell Doctrine, you can take -- I mean, you can run through a litany of lessons.

Mr. Burns: Let me ask you something. You're on the diplomatic side now, but obviously that diplomatic side is intricately tied with the military considerations. And we tend to, as we made the film in Vietnam, realize that we were hearing echoes ahead to Afghanistan, echoes ahead to Iraq, to Syria. Now, today they're not mentioned, but they bubble up, that what has been is now. But it occurs to me too that we have to look at this from the angle of perpetual war. Eisenhower at the end of the ‘50s warned us about the military-industrial complex, and to the extent that we can fashion lessons that are easily identifiable with a particular conflict like Iraq or Afghanistan or Syria, we also have to understand that we're also the victims of kind of momentum of warfare as a kind of perpetual state. I mean, even Dr. Kissinger was talking about this last night.

Secretary Kerry: I wish I had heard him. I wish I'd heard how he phrased that. I've had -- I've talked to him a number of times, obviously, in the last years about these challenges. What he's said to me is that we're dealing with, first of all, a very, very different world from the world that he dealt with, and he acknowledges that right up front. And if you read his book, "Diplomacy," which I've read several times -- it's brilliant -- he talks about balance of power, interests and state interests, and so forth. And that was the world that really defined -- I mean, that's Disraeli and Metternich and so forth. I mean, that's 18th, 19th centuries and so forth.

The 20th century was far more defined, I think, in the bipolar way because of the strength we had coming out of World War I, the unfinished business of World War I which was World War II, and then of course we were the only economic power left standing. But we understood what we were trying to go to with the United Nations, with global pacts and agreements on human rights and on universal values and so forth, which were translated into these international institutions. And then with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War, forces have been unleashed together with the profound impact of technology and globalization, which has come with technology, and so all of a sudden the world is smaller and now you've got millions of people running around with smartphones in poor countries, poor people, but who see and know what everybody else is doing and thinking and getting on a daily basis. And it changes everything.

And Kissinger, I think -- so I don't agree with your -- actually, with this notion that war per -- I think we're in a different cycle now. We're not seeing a moment -- despite what Russia is doing in Ukraine. There's a reason Russia didn't go to Kyiv. And there's a reason there are limits to what it is doing and will do and can do in Syria. And I think what we are seeing today is less the 20th century of nation states being willing to go to war with massive kinds of casualties as a consequence of the kinds of weapons we chose to use. Now we have non-state actors as the principal threat to every nation-state. That's a different equation. And when you're struggle is against one human being who if they decide they want to kill themselves can go out and take 100 people or 200 people with them, or more in the case of 9/11, et cetera, it's a very asymmetrical struggle because we, the government, have to get it right 24/7, 365, and they only have to get it right a few hours or minutes of a day. And what I think we're seeing today. And I think the greatest challenge -- just quickly, the greatest challenge we face, which is why I say we can't be the prisoners of Vietnam.

Mr. Burns: Right.

Secretary Kerry: It's different. And we have to see it differently. I think the challenge today is that we're not -- the world, particularly the Western world, the developed world particularly is not doing enough to protect ourselves by investing in the long-term initiatives that will keep people from becoming terrorists because they actually have a future and there is decent governance in their country and they can get a job ultimately and share in what we translate to people as the American dream and our values.

Mr. Burns: In your extraordinary effort at normalization, you had the opportunity to meet with a lot of the leaders of North Vietnam and some of the people who you were fighting against in that war. How did your interactions then in the late ‘80s and ‘90s with the Vietnamese modify or change, maybe even enhance your understanding of the conflict?

Secretary Kerry: I don't want to disappoint you. But I have to tell you truthfully, it didn't really change my understanding of the conflict, which I'd already spent a lot of energy when I was there and when I immediately came back trying to understand, and I talked pretty publicly about it. What it did was inform me about our former adversary in a way that you were talking about.

Mr. Burns: Yes.

Secretary Kerry: It instructed me about how just unbelievably disciplined and patient and open and ready to be sort of fair-minded and thoughtful, but nevertheless obviously hurt by the [inaudible] -- but it taught me to see how they saw the war. To us -- it was not the Vietnam War, it was the American war to them. And to them it was the American war that followed the French war that came before the Chinese war that followed the first Chinese war and that came after -- you know? We didn't see any of that. We never thought about sort of that longer view and long sense of things. And obviously we completely missed the internal dynamics and struggle of North and South, the civil component of that.

But it really refreshed, in a sense, my -- and it was very difficult, I might add, because it refreshed my sense of these folks in a way that gave me confidence to come back and try to proceed with the normalization. But it certainly wasn't something that penetrated easy the body politic of the United States. So the suspicions that still existed -- I mean, in the early 1990s, Newsweek Magazine carried a cover story of live prisoners still being held in Vietnam. That's the mood that John McCain and I entered into as we came together to agree that we were going to try to move this process forward beginning with the POW/MIA. And it was an extraordinary journey. I mean, we spent 10 years doing that, trying to get enough confidence that we could put out a report which ultimately all 12 members of the POW/MIA committee signed, split evenly Republican and Democrat. It was quite remarkable.

Mr. Burns: How did you -- I mean, this is an early diplomatic experience of you, but I mean, hindsight is so easy. How did you two, and I guess Bob Kerry to some extent, even think that that was possible and how did that -- those diplomatic efforts inform your current work as Secretary of State?

Secretary Kerry: Well, the current work is informed by probably the lessons of patience and tenacity. I will tell you there were some unbelievably hairy moments where I thought the whole thing could blow up. There was one time where we were going to go into a prison outside of Saigon, then Saigon -- not then Saigon, but for a lot of people Saigon -- and we were taking a New York Times reporter with us and ABC and a couple of other media people because the whole purpose of the trip was to prove that it was spontaneous and we could get in and people could see that there was nothing there, or that we -- the evidence was not there -- and we got there and some local official had not gotten the word and the place was closed. And I -- for a moment I said, okay, five years' work is about to blow up in smoke and this will feed all the conspiracies and so forth. But to the credit of the Vietnamese, we had the leadership fully invested in this and I was able to get on the phone and call the foreign minister, who was able to call somebody, and a half hour later we broke the walls down and we got in, and it actually turned out better because the fact that the local guy refused entrance and hadn't gotten the word and then on the moment we broke it open and got in there, people had total confidence of the spontaneity of it, and it actually turned out to be -- we couldn't have staged it better if we'd tried. So it worked.

And then another time -- a story I've not told in public, but I have -- I should probably reserve it for memoir but I won't. I'll tell you a little bit tonight. I had to go in to the chairperson -- the chairman of the Community Party and the president of the nation and persuade them to allow me and another senator to go down underneath the tomb of Ho Chi Minh because there was intelligence information that there were tunnels under there and there was a possibility that people were being held. And you can imagine what it was like to sit with the chairman of the party with a big bust of Ho above you and I'm telling him, "I got to go down and check out whether there's anybody underneath Ho." It was pretty amazing and we did it, and I won't tell you the rest of the story about what it was like or what happened.

Mr. Burns: We anxiously await those memoirs.

Secretary Kerry: It was amazing. That's what I want. You have to actually anxiously wait.

Mr. Burns: The -- this idea maybe not of perpetual war but of the lessons learned from Vietnam or perhaps missed in various conflicts that we've had since, the Iran deal stands, as Mr. Barnes said so eloquently, "in stark contrast to that," and it seems that you and the President have been able to arrest a momentum or a default practice of war. I'm impressed by that. Can you talk about that? That was an extraordinary achievement. I mean, many Americans disagree, but I think the notion that in an age when the response to everything is let's go in there and put the boots on the ground --

Secretary Kerry: Sure.

Mr. Burns: -- this was the opposite of that, and you placed faith in a tenuous at best outcome that seems to have been at least so far -- knock on wood -- good for everybody.

Secretary Kerry: Well, look, I believe -- President Obama and I have talked about this frequently a number of times. I learned through the war and have said many times that one of the principal obligations of anybody in the highest positions of responsibility and certainly the presidency is if you are going to make -- if you are going to ask young men and women to go and put their lives on the line and if not die suffer perhaps grievous injury and live with whatever kind of injury for the rest of their lives, you better make damn sure you have tried everything possible that is legitimate to first exercise diplomacy and make war the last resort. That is critical.

And those of us who were privileged to come back from Vietnam -- whole, particularly -- and my guys on my crew, we still kick it around, we get together, and we have a saying: every day is extra. And it's true, every day is extra. And it gives you the opportunity, particularly since I am now in a position of responsibility, to live those -- to live my beliefs and to live my lessons. And I think that the President, I know, shares that belief. He was deeply impacted by the funerals and the letters he had to write and what you have to go through in terms of Afghanistan, Iraq, and so forth, and other efforts.

So you'd think this was common sense, but it's not the automatic instinct of everybody, obviously.

Mr. Burns: And how did this -- I mean, this President was a little boy during Vietnam. How did he get --

Secretary Kerry: Well, he's a smart man, and he learned a lot.

Mr. Burns: I think he understood the lesson of Vietnam.

Secretary Kerry: He did. I think he understood the lesson of Vietnam, and more. And I think the President -- I mean, has struck me by how thoughtful he is in the questions that he asks and the way that he probes with respect to the options that are put in front of him. And my sense is that we also are living in a different -- in a different world, different set of choices.

Let me be more precise. There are places where we have no choice. I am not a pacifist.

Mr. Burns: No?

Secretary Kerry: Even after the experience of war. And I've read a lot about war -- I read a lot about World War I, a lot about World War II particularly. I know you have Joe Galloway here. One of the battles I most admire and one of the greatest examples of American guts and prowess was the Battle of Ia Drang Valley. And there were many examples of that, and I think every Vietnam vet sometimes probably bristles a little bit about the greatest generation references, because I think people feel like they fought just as passionately, just as valiantly, and gave as much of themselves. But the outcome, obviously, was different, the structure was different, and that's part of the tension that we live with. That's part of what you were talking about a little while ago. It wasn't -- it didn't invite a great victory parade. There wasn't some denouement where you dropped a bomb and -- I was just in Hiroshima, and you can end a war where the war in Europe had already ended and Hitler was dead. It wasn't that. And so that's not very satisfying for anybody, particularly the people who fight in it. And that's one of the reasons there's a lingering anger by some people who haven't necessarily worked through, as you talked about, and won't, perhaps -- particularly those who will not see film -- that has an impact.

But I think that we're living in a period now where we have to call on people, unfortunately, to go into harm's way, particularly against Daesh and some other people who threaten us and with whom there is nothing to negotiate. I mean, where do you begin? There is no negotiation. And particularly when they threaten and tell you that unless you are going to be them and be like them and convert and do a whole bunch of things --

Mr. Burns: They'll kill you.

Secretary Kerry: -- you're the infidel, and doomed to be displaced.

Mr. Burns: You spoke in your remarks about one of the big lessons having to do with not blaming the warrior. I think that is a lesson that we've learned, all of us, regardless of our political --

Secretary Kerry: Well, we have and we haven't, Ken.

Mr. Burns: But I want to ask you whether the fact that we now have an all-volunteer army that suffers, as Lynn and Mark [ph] and I were talking, its loss is apart and alone from everyone, separates us and permits us both the luxury of that respect, but also the distance that that permits as well. And I think to some extent we hide behind a kind of false patriotism about that -- many Americans do.

Secretary Kerry: Well, I'm not going to judge whether it's false patriotism or not; I don't know. But I think there is a separation. And it's a dangerous separation. And there is the kind of permissiveness which has been talked about. It's -- and that is dangerous, I agree.

Mr. Burns: Yes.

Secretary Kerry: I have always had -- I mean, I'm not -- now I'm ranging a little bit into the issues that I don't touch on much very much in my current role -- and try not to, I might add -- but in the spirit of this evening, I will -- I would just say that I have deep reservations about just an all-volunteer military. And I think that there should be shared responsibility among all Americans and all responsibility. And I think that's one of the best ways that you don't have wars, that if you're spreading that -- one of the great difficulties we had in Vietnam was the way the draft was applied. And that created enormous resentment and anger. It's one of the things that probably still lingers as a tension in relationships. But I think every American ought to find a way to serve somehow. It doesn't have to be in the military; there are plenty of other things to do. But I rather like still the idea that everybody ought to give back something.

Mr. Burns: I think I'd agree. The war in Vietnam had an immense impact on a whole generation of us, of Americans, and of course, also a whole generation of Vietnamese and Cambodians and Laotians. When you look back at what's happened in Afghanistan and Iraq and now Syria for the past 5, 10, 15 years, what are your thoughts about the potential long-term impacts there for those people, for those societies? And to what extent do those thoughts influence your views concerning the importance of diplomacy and choices you're making every day in the Middle East, which seems still -- still -- the center of all of our concern?

Secretary Kerry: It affects it profoundly. I mean, it's a big deal in those countries. And I'll come back to that in a minute, because I just thought of something that I wanted to share with people, because it's important to take away from here. You mentioned a moment ago you thought that we had learned a lesson, and I said for the most part.

Mr. Burns: Yeah.

Secretary Kerry: And I want to share with people why I say "for the most part." We do welcome people home. We do say thank you. And we have lots of ways in which we have built into our daily lives a recognition for service -- Hire the Veteran programs, outreach programs, service people who can get a first-class seat on a plane if it's open, different things that we say thank you, and that's superb, wonderful, and totally well deserved.

But there are more meaningful things to veterans coming home from war. And we still have too long a backlog. We've had 188 -- we've had a reduction of about 180-plus days in the wait time for people to be able to get into the VA and get an appointment. But that's still -- that's 188 days taken away from 282 days that it took to get there. That's still too long -- 90 days, whatever it is that it works out -- it's somewhere in that vicinity. It's just wrong. It's not right. I mean, let's get down to four days, a week, and in some cases, that's the difference between life and death.

Mr. Burns: Right.

Secretary Kerry: And -- I think -- so for mental health particularly we need greater intervention and activity. There are other things that matter; families need more help. There are a lot of families for whom this is extraordinarily disruptive.

Mr. Burns: Yes, of course.

Secretary Kerry: And women. Women particularly have a different set of health problems, and sometimes abuse problems that they have to respond to, so that's also been complicated.

So there are things that we need to do even more effectively. And I might add one of the dangers of what we have today in the, quote -- in this volunteer structure, is I've met people who are on their fifth and sixth deployments to a Afghanistan or Iraq or somewhere. And that's -- boy is that tough. I mean, that is just really hard for people to hold a family together, raise kids, and do the things we expect. So we got to confront this as a country. That's part of what I say about sharing it more and being willing to do what we need to do.

I'll probably get in trouble for this, but years ago I proposed -- and I think there are others who've talked about it -- that vets who want to go to the Veterans Administration go to the Veterans Administration. They deserve the hospital they want and deserve the choice. But those who can't get in or it's too late, who need to go somewhere, ought to be able to go somewhere else, and we ought to be able to take care of them.

Mr. Burns: So I would withdraw my false patriotism comment and say more that, as I think you've done so articulately, Mr. Secretary, that we have paid a kind of common and easy respect to the veteran, but the harder work of having the resources necessary to reduce that wait time --

Secretary Kerry: Sure.

Mr. Burns: -- and all the other things --

Secretary Kerry: Are tough.

Mr. Burns: -- you just described is the work that still has to be done.

Secretary Kerry: Now, let me come to your other -- to your question, because it's an important question. In every country, you can go to -- you go to the Czech Republic and they're still worried about a war that happened in 1600-and-something, and you can go to -- obviously, you go anywhere in the Middle East and you can learn, which I know all the details of to a fare-thee-well about Karbala in 682 and what happened to Hussain and the fight for legitimacy between Twelvers and Seveners and so -- it's extraordinary, which is why I gave a speech last night in Houston about the importance of religion in the context to understanding it and reaching out and working with various religious entities and groups as you try to do good foreign policy, because you can't do it today in today's world. Four out of five people on the planet are affiliated with one religion or another, and many of them are able to take it to some very risky, dangerous places. And if you think back historically on the Thirty Years' War, and other things, we shouldn't claim any primacy in our ability to avoid that kind of memory -- Northern Ireland and other places.

So my point is we got to think very carefully about the impression that we are leaving and what we are doing in various places because this can become the long-term -- I mean, look at the Crusades and look at their impact on people's attitude about some of the things that we choose to do or not do today in the Middle East. It still comes up. So we have to be, I think, particularly sensitive to the aftermath and to what the long-term vision is for how we are going to manage to transition people where we want them to go in Afghanistan, in Iraq, and elsewhere.

And trust me, it is complicated beyond what I had even imagined in the beginning, many people -- we've got about six wars going on in Syria. Now, most of you would probably not have thought that. But you've got Kurds versus Turkey. You've got Saudi Arabia versus Iran. You've got Sunni versus Shia. You got a whole bunch of people versus Daesh/ISIL. And then you got a whole bunch of people against Assad. And that's before you get into some tribal and other things that go back to Karbala or before.

So this is -- it's -- they're -- and then you have an enormous Muslim Brotherhood challenge with respect to --

Mr. Burns: Egypt.

Secretary Kerry: -- Egypt and its attitude about Qatar and Turkey and Saudi versus other Arab countries in the region who have a slightly different -- so you put all those in a caldron and bubble it up, it's not easy to find the way to go forward. And that's why I think we have to think very -- that's the lens I'm talking about. That is a lesson from Vietnam, is we cannot look at other countries and see them only through an American lens. We have to try and put ourselves wherever we are into the other person's shoes, into the other person's life, and see their country as they see their country, and we'll do a lot better.

Mr. Burns: I just had the opportunity to spend some time discussing with a mentor -- somebody you know, Tom Brokaw -- a thorny problem that I had in an unrelated subject. And he said to me, "What we learn is more important than what we set out to do." And I think, Mr. Secretary, there's not a person here in this room who doesn't appreciate that you would spend one of your extra days with us. Thank you very much.

Secretary Kerry: Thank you. My pleasure, honestly.

Book/CDs by Michael E. Eidenmuller, Published by

McGraw-Hill (2008)

Book/CDs by Michael E. Eidenmuller, Published by

McGraw-Hill (2008)

Text and Image #1 Source: State.gov

Image #2 Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org

Audio Source: C-SPAN.org

U.S. Copyright Status: Text, Audio, Images = Public domain.