|

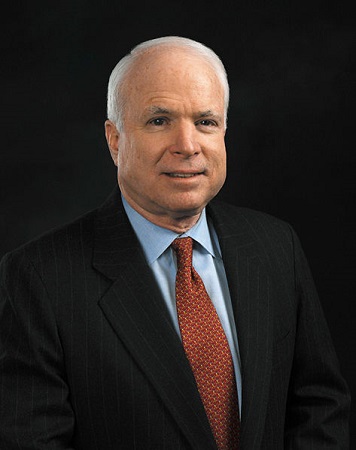

John McCain Liberty University Commencement Address delivered 13 May 2006

[AUTHENTICITY CERTIFIED: Text version below transcribed directly from audio] Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you, Dr. Falwell. Thank you, faculty, families and friends, and thank you Liberty University Class of 2006 for your welcome and your kind invitation to give this yearís commencement address. I want to join in the chorus of congratulations to the Class of 2006. This is a day to bask in praise. Youíve earned it. You have succeeded in a demanding course of instruction. Life seems full of promise as is always the case when a passage in life is marked by significant accomplishment. Today, it might seem as if the world attends you. But spare a moment for those who have truly attended you so well for so long, and whose pride in your accomplishments is even greater than your own -- your parents. When the world was looking elsewhere your parents' attention was one of lifeís certainties. So, as I commend you, I offer equal praise to your parents for the sacrifices they made for you, for their confidence in you and their love. More than any other influence in your lives they have helped you -- make you the success you are today and might become tomorrow. Thousands of commencement addresses are given every year, many by people with greater eloquence and more original minds than I possess. And itís difficult on such occasions to avoid resorting to clichťs. So let me just say that I wish you all well. This is a wonderful time to be young. Life will offer you ways to use your education, industry, and intelligence to achieve personal success in your chosen professions. And it will also offer you chances to know a far more sublime happiness by serving something greater than your self-interest. I hope you make the most of all your opportunities. When I was in your situation, many, many years ago, an undistinguished graduate -- barely -- of the Naval Academy, I listened to President Eisenhower deliver the commencement address. I admired President Eisenhower greatly. But I must admit I remember little of his remarks that day, impatient as I was to enjoy the less formal celebration of graduation, and mindful that given my class standing I would not have the privilege of shaking the Presidentís hand. I do recall, vaguely, that he encouraged his audience of new navy ensigns and Marine lieutenants to become "crusaders for peace." I became an aviator and, eventually, an instrument of war in Vietnam. I believed, as did many of my friends, we were defending the cause of a just peace. Some Americans believed we were agents of American imperialism who were not overly troubled by the many tragedies of war and the difficult moral dilemmas that constantly confront our soldiers. Ours is a noisy, contentious society, and always has been, for we love our liberties much. And among those liberties we love most, particularly so when we are young, is our right to self-expression. That passion for self-expression sometimes overwhelms our civility, and our presumption that those with whom we may have strong disagreements, wrong as they might be, believe that they, too, are answering the demands of their conscience. When I was a young man, I was quite infatuated with self-expression, and rightly so because, if memory conveniently serves, I was so much more eloquent, well-informed, and wiser than anyone else I knew. It seemed I understood the world and the purpose of life so much more profoundly than most people. I believed that to be especially true with many of my elders, people whose only accomplishment, as far as I could tell, was that they'd been born before me, and, consequently, had suffered some number of years deprived of my insights. I had opinions on everything, and I was always right. I loved to argue, and I could become understandably belligerent with people who lacked the grace and intelligence to agree with me. With my superior qualities so obvious, it was an intolerable hardship to have to suffer fools gladly. So I rarely did. All their resistance to my brilliantly conceived and cogently argued views proved was that they possessed an inferior intellect and a weaker character than God had blessed me with, and I felt it was my clear duty to so inform them. Itís a pity that there wasnít a blogosphere then. I would have felt very much at home in that medium. Itís funny, now, how less self-assured I feel late in life than I did when I lived in perpetual springtime. Some of my critics allege that age hasnít entirely cost me the conceits of my youth. All I can say to them is, they should have known me then, when I was brave and true and better looking than I am at present. But as the great poet, Yeats, wrote, "All thatís beautiful drifts away, like the waters." I've lost some of the attributes that were the object of a young manís vanity. But there have been compensations, which I have come to hold dear. We have our disagreements, we Americans. We contend regularly and enthusiastically over many questions: over the size and purposes of our government; over the social responsibilities we accept in accord with the dictates of our consciousness [conscience] and our faithfulness to the God we pray to; over our role in the world and how to defend our security interests and values in places where they are threatened. These are important questions; worth arguing about. We should contend over them with one another. It is more than appropriate: It is necessary that even in times of crisis, especially in times of crisis, we fight among ourselves for the things we believe in. It is not just our right, but our civic and moral obligation. Our country doesnít depend on the heroism of every citizen. But all of us should be worthy of the sacrifices made on our behalf. We have to love our freedom, not just for the private opportunities its [sic] provides, but for the goodness it makes possible. We have to love it as much, even if not as heroically, as the brave Americans who defend us at the risk and often the cost of their lives. We must love it enough to argue about it, and to serve it, in whatever way our abilities permit and our conscience requires, whether it calls us to arms or to altruism or to politics. I supported the decision to go to war in Iraq. Many Americans did not. My patriotism and my conscience required me to support it and to engage in the debate over whether and how to fight it. I stand that ground not to chase vainglorious dreams of empire; not for a noxious sense of racial superiority over a subject people; not for cheap oil (we could have purchased oil from the former dictator at a price far less expensive than the blood and treasure weíve paid to secure those resources for the people of that nation); not for the allure of chauvinism, to wreck [wreak] destruction in the world in order to feel superior to it; not for a foolishly romantic conception of war. I stand that ground because I believed, rightly or wrongly, that my countryís interests and values required it. War is an awful business. The lives of the nationís finest patriots are sacrificed. Innocent people suffer. Commerce is disrupted, economies damaged. Strategic interests shielded by years of statecraft are endangered as the demands of war and diplomacy conflict. Whether the cause was necessary or not, whether it was just or not, we should all shed a tear for all that is lost when war claims its wages from us. However just or false the cause, how ever proud and noble the service, it is loss -- the loss of friendships, the loss of innocent life, the innocence -- the loss of innocence; and the veteran feels most keenly forever more. Only a fool or a fraud sentimentalizes war. Americans should argue about this war. They should argue about it. It has cost the lives of nearly 2500 of the best of us. It has taken innocent life. It has imposed an enormous financial burden on our economy. At a minimum, it has complicated our ability to respond to other looming threats. Should we lose this war, our defeat will be further destabilize an already volatile and dangerous region, strengthen the threat of terrorism, and unleash furies that will assail us for a very long time. I believe the benefits of success will justify the costs and the risks we have incurred. But if an American feels the decision was unwise, then they should state their opposition, and argue for another course. It is your right and your obligation. I respect you for it. I would not respect you if you chose to ignore such an important responsibility. But I ask that you consider the possibility that I, too, am trying to meet my responsibilities, to follow my conscience, to do my duty as best as I can, as God has given me light to see that duty. Americans deserve more than tolerance from one another; we deserve each otherís respect, whether we think each other right or wrong in our views, as long as our character and our sincerity merit respect, and as long as we share, for all our differences, for all the noisy debates that enliven our politics, a mutual devotion to the sublime idea that this nation was conceived in -- that freedom is the inalienable right of mankind, and in accord with the laws of nature and natureís Creator. We have so much more that unites us than divides us. We need only to look to the enemy who now confronts us, and the benighted ideals to which Islamic extremists pledge allegiance -- their disdain for the rights of Man, their contempt for human life -- to appreciate how much unites us. Take, for example, the awful human catastrophe under way in the Darfur region of the Sudan. If the United States and the West can be criticized for our role in this catastrophe it's because we have waited too long to intervene to protect the multitudes who are suffering, dying because of it. Twelve years ago, we turned a blind eye to another genocide, in Rwanda. And when that reign of terror finally, mercifully exhausted itself, with over 800,000 Rwandans slaughtered, Americans, our government, and decent people everywhere in the world were shocked and ashamed of our silence and inaction, for ignoring our values, and the demands of our conscience. In shame and renewed allegiance to our ideals, we swore, not for the first time, ďnever again.Ē But never lasted only until the tragedy of Darfur. Now, belatedly, we have recovered our moral sense of duty, and we are prepared, I hope, to put an end to this genocide. Osama bin Laden and his followers, ready, as always, to sacrifice anything and anyone to their hatred of the West and our ideals, have called on Muslims to rise up against any Westerner who dares intervene to stop the genocide, even though Muslims, hundreds of thousands of Muslims, are its victims. Now that, my friends, is a difference, a cause, worth taking up arms against. It is not a clash of civilizations. I believe, as I hope all Americans would believe, that no matter where people live, no matter their history or religious beliefs or the size of their GDP, all people share the desire to be free; to make by their own choices and industry better lives for themselves and their children. Human rights exist above the state and beyond history -- they are God-given. They cannot be rescinded by one government any more than they can be granted by another. They inhabit the human heart, and from there, though they can be abridged, they can never be wrenched. This is a clash of ideals, a profound and terrible clash of ideals. It is a fight between right and wrong. Relativism has no place in this confrontation. We're not defending -- We're not defending an idea that every human being should eat corn flakes, play baseball, or watch MTV. Weíre not insisting that all societies be governed by a bicameral legislature and a term-limited chief executive. We're insisting that all people have a right to be free, and that right is not subject to the whims and interests and authority of another person, government, or culture. Relativism, in this contest, is most certainly not a sign of our humility or ecumenism; it is a mask for arrogance and selfishness. It is, and I mean this sincerely and with all humility, not worthy of us. We are a better people than that. We're not a perfect nation. Our history has had its moments of shame and profound regret. But what we have achieved in our brief history is irrefutable proof that a nation conceived in liberty will prove stronger, more decent, and more enduring than any nation ordered to exalt the few at the expense of the many or made from a common race or culture or to preserve traditions that have no greater attribute than longevity. As blessed as we are, no nation complacent in its greatness can long sustain it. We, too, must prove, as those who came before us proved, that a people free to act in their own interests, will perceive those interests in an enlightened way, will live as one nation, in a kinship of ideals, and make of our power and wealth a civilization for the ages, a civilization in which all people share in the promise and responsibilities of freedom. Should we claim our rights and leave to others the duty to the ideals that protect them, whatever we gain for ourselves will be of little lasting value. It will build no monuments to virtue, claim no honored place in the memory of posterity, offer no worthy summons to the world. Success, wealth and celebrity gained and kept for private interest is a small thing. It makes us comfortable, eases the material hardships our children will bear, purchase[s] a fleeting regard for our lives, yet not the self-respect that, in the end, matters most. But sacrifice for a cause greater than yourself, and you invest your life with the eminence of that cause, your self-respect assured. All lives are a struggle against selfishness. All my life Iíve stood a little apart from institutions that I willingly joined. It just felt natural to me. But if my life had shared no common purpose, it would not have amounted to much more than eccentricity. There is no honor or happiness in just being strong enough to be left alone. I've spent nearly fifty years in the service of this country and its ideals. I have made many mistakes, and I have many regrets. But I've never lived a day, in good times or bad, that I wasnít grateful for the privilege. Thatís the benefit of service to a country that is an idea and a cause, a righteous idea and cause. America and her ideals helped spare me from the weaknesses in my own character. And I cannot forget it. When I was a young man, I thought glory was the highest attainment, and all glory was self-glory. My parents had tried to teach me otherwise, as did my church, as did the Naval Academy. But I didnít understand the lesson until later in life, when I confronted challenges I never expected to face. In that confrontation, I discovered that I was dependent on others to a greater extent than I had ever realized, but neither they nor the cause we served made any claims on my identity. On the contrary, they gave me a larger sense of myself than I had had before. And I am a better man for it. I discovered that nothing in life is more liberating than to fight for a cause that encompasses you but is not defined by your existence alone. And that has made all the difference, my friends, all the differences in the world. Let -- Let us argue with each other then. By all means, let us argue. Our differences are not petty. They often involve cherished beliefs, and represent our best judgment about what is right for our country and humanity. Let us defend those beliefs. Letís do so sincerely and strenuously. It is our right and duty to do so. And letís not be too dismayed with the tenor and passion of our arguments, even when they wound us. We have fought among ourselves before in our history, over big things and small, with worse vitriol and bitterness than we experience today. Let us exercise our responsibilities as free people. But let us remember, we are not enemies. We are compatriots defending ourselves from a real enemy. We have nothing to fear from each other. We are arguing over the means to better secure our freedom, promote the general welfare, and defend our ideals. It should remain an argument among friends; each of us struggling to hear our conscience, and heed its demands; each of us, despite our differences, united in our great cause, and respectful of the goodness in each other. I have not always heeded that injunction myself, and I regret it very much. I had a friend once, who, a long time ago, in the passions and resentments of a tumultuous era in our history, I might have considered my enemy. He had come once to the capitol of the country that held me prisoner, that deprived me and my dearest friends of our most basic rights, and that murdered some of us. He came to that place to denounce our countryís involvement in the war that had led us there. His speech was broadcast into our cells. I thought it a grievous wrong then, and I still do. A few years later, he had moved temporarily to a kibbutz in Israel. He was there during the Yom Kippur War, when he witnessed the support America provided our beleaguered ally. He saw the huge cargo planes bearing the insignia of the United States Air Force rushing emergency supplies into that country. And he had an epiphany. He had believed America had made a tragic mistake by going to Vietnam, and he still did. He had seen what he believed were his countryís faults, and he still saw them. But he realized he has -- he had let his criticism temporarily blind him to his countryís generosity and the goodness that most Americans possess, and he regretted his failing deeply. When he returned to his country he became prominent in Democratic Party politics, and helped [elect] Bill Clinton President of the United States. He criticized his government when he thought it wrong, but he never again lost sight of all that unites us. We met some years later. He approached me and asked to apologize for the mistake he believed he had made as a young man. Many years had passed since then, and I bore little animosity for anyone because of what they had done or not done during the Vietnam War. It was an easy thing to accept such a decent act, and we moved beyond our old grievance. We worked together in an organization dedicated to promoting human rights in the country where he and I had once come for different reasons. I came to admire him for his generosity, his passion for his ideals, and for the largeness of his heart, and I realized he had not been my enemy, but my countryman, my countryman, and later my friend. His friendship honored me. We disagreed over much. Our politics were often opposed, and we argued those disagreements. But we worked together for our shared ideals. We were not always in the right, but we werenít always in the wrong either, and we defended our beliefs as we had each been given the wisdom to defend them. David [Ifshin] remained my countryman and my friend, until the day of his death, at the age of forty-seven, when he left a loving wife and three beautiful children, and legions of friends behind him. His country was a better place for his service to Her, and I had become a better man for my friendship with him. God bless him.

And may God bless you, Class of 2006. The world does indeed await

you, and humanity is impatient for your service. Take good care of

that responsibility. Everything depends upon it.

Research Note:

Audio provided by Joseph Slife, Emmanuel College Communication Dept.

(Franklin Springs, Ga.)

Page Updated: 6/4/19 U.S. Copyright Status: Text = Public domain. Audio = Uncertain. |

|

|

© Copyright 2001-Present. |