|

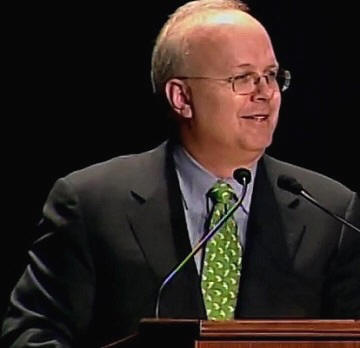

Karl Rove Address to the Federalist Society delivered 10 November 2005, Washington, D.C.

[AUTHENTICITY CERTIFIED: Text version below transcribed directly from audio.] Thank you. Enough! Sit down. You'll get your dinner quicker. Thank you, David. Thank you very much for the generous introduction. You know, for some it's the Bavarian Illuminati. For others, it's the Knights Templar. In recent years it's been the Trilateralists, the Bilderbergers, or the neocons. But for Senators Kennedy, Durbin, Schumer and Lahey, the most successful conspiracy in the history of the mankind is one of the most visible and open, as shown by your willingness to put yourselves on display here tonight. Who would've thought that powerful members of the world's most exclusive club would be so threatened by a movement of confident, principle-driven, egghead lawyers? So, I say good evening, fellow Federalists.

I gotta say, I'm mighty impressed that you found out that I was one. I mean after all, you know, it's a not well-known secret that -- that I am. How did you find the records from the 1968 Utah Boys State and find out I was a member of the Federalist Party? I mean I -- it's beyond me. We're talking the same federalism, aren't we? You know every conspiracy needs a leader of vision who thinks long into the future, who plays the game and has had many moves ahead, and you of course have that in your president, Gene Meyer -- international chess master, I found in his biography. Now I understand how the guy thinks ahead so far. So every conspiracy needs that kind of person and you got one. Every conspiracy needs an Agent Provocateur. You've got one in your Executive Vice President, Leonard Leo. Every conspiracy needs a grey eminence, and tonight I understand you're honoring your grey eminence, Ed Meese. It was great to be with other members of your executive committee. They came by the White House today -- There are only about four or five pieces of silverware missing from the Roosevelt Room -- Steve Calabrese, Gary Lawson, and Ken Cribb whom I've known longer then either one of us wants to admit. As I was looking around the crowd here tonight I see that we -- virtually everybody in this audience is -- falls into one of three classifications of people. First of all, honored to have members of the federal judiciary here, and the state judiciary. So we have a bunch of judges. I saw a couple of our nominees to the bench. Fred Cavanaugh and I crossed paths here recently. (Fred, where are you?) Any of you nominees just remember you wanted the job. And, of course, the final group of people who are here tonight are aspiring judges, so my advice to you is save your money, buy a little Kelvar [Kevlar] jacket and hope you get in the chance to get in the process 'cause it's not going to get any better soon. You've also got here a friend of mine that I'd like to just say a word about because I've known her for 15 years. Back in Texas when the Supreme Court of Texas was a disaster -- I'll have a little bit more to say about that later -- she was one of the few people in the legal community who stood up and said we need to do something to change it, and I worked with her awfully, you know, for an awfully long time to see us get the changes we wanted in the judiciary, and she was a warrior. And I've worked with her the last five years and have really gotten to know her well. In the last three years, we've served together on the judicial selection committee at the White House, and for me, the non-lawyer, it's been a fantastic experience -- been like attending a graduate seminar in legal theory. If you like every one of the 200 judges that we've sent to forward to the U.S. Congress to be approved, in the last three years there hasn't been one of them who hasn't been researched, vetted, studied, analyzed, and recommended by my friend, Harriet Meyers -- legal council to the President. It is an honor to be here tonight. The Federalist Society is one of America's most important intellectual movements. Since your founding more than 20 years ago, you have made extraordinary efforts to return our country to constitutionalism. You've developed new generations of lawyers, judges, and legal scholars who are committed to that vision. And you've shaped America's legal, cultural, and political landscape in a very constructive way. Consider where America stands today versus where it stood when the great William Rehnquist was named to the High Court in 1972. That was right about the time that judicial activism was most dominant. And yet, today, the wind and tide are running in our favor -- due in large measure to the efforts your organization. I admire the Federalist Society for the commitment and energy of its members, and for their intellectual rigor and effectiveness. One of George W. Bush's greatest contributions as President will be the changes he's brought about in our courts and our legal culture, and those changes would have been impossible were it not for the Federalist Society. You've also thoroughly infiltrated the ranks of the White House. In fact, there are so many Federalists in the Administration that Andy Card, Chief of Staff, has asked me to say that there will be a special staff meeting in the back of the room, near the back doors, at the end of the dinner. We'll be discussing an important legal question, namely, the application of the principle of equidistance in the determination of seaward lateral boundaries. I, incidentally, while not a lawyer am the leading White House expert on this issue. I be -- will be leading the meeting. You know, I've thought long and hard about how to begin the formal part of my remarks. I scoured the Toastmaster books. I talked with a few fine speakers that I know. I sat in Mike Gershen's office for about an hour and a half. He wasn't there. I even called up Peggy Noonan. And the consistent advice I got was to start my remarks in a way that the audience would find comfortable and familiar and reassuring. They said it's not the words, but it's the structure of what you say. They ought to be able to sort of connect with it. So, that sounds about right to me. So here goes: My name is Karl and I'm not a lawyer. I say that with no sense of superiority. Instead, I offer it as a reminder of what must be a painful point for all of you with a J.D. Believe it or not, 99.7% of all Americans are not lawyers. We may not have the power, but we are the majority. And it is clear today that many ordinary men and women, non-lawyers, believe our courts are in crisis. And their concerns are well-grounded. I've seen this phenomenon myself for several decades. In the 1980s, in my home state of Texas, our Supreme Court was dominated by justices determined to legislate from the bench, bending the law to fit a personal agenda. Millions of dollars from a handful of wealthy personal injury trial lawyers were poured into Supreme Court races to shift the philosophical direction of the Court. It earned the reputation, as the Dallas Morning News said, as quote, "the best court that money could buy." Even 60 Minutes was troubled, and it takes a lot to trouble CBS. In 1987 it did a story on the Texas Supreme Court titled "Justice for Sale." Ordinary Texans had had enough, and they took it upon themselves to change the Court. In a bipartisan reform effort, they recruited and then elected to the Texas Supreme Court distinguished individuals like Tom Phillips, Alberto Gonzales, John Cornyn, Priscilla Owen, Nathan Hecht, and Greg Abbott. And for those of you -- And for those of you [who] know something about Texas politics, this is pretty significant because all of them were Republicans. After all, Texas had gone for a mere 120 years without electing a single Republican to our Supreme Court, and then all of a sudden we were blessed with these extraordinarily able people. I saw this public reaction to judicial activism again in Alabama. The state legislature passed tort-reform legislation in 1987. However, activist judges on the -- on the Supreme Court, the trial lawyer-friendly Supreme Court, struck it down, prompting a period of "jackpot justice" at Alabama through the mid-1990s, where the median punitive-damage award in Alabama reached 250,000 dollars -- three times the national average. Time Magazine labeled Alabama "tort hell." Like in Texas, this led to a popular revolt against judicial activism. It began in 1994, when Republican Perry Hooper challenged sitting Chief Justice and trial lawyer favorite Sonny Hornsby. Hooper pulled off a stunning upset -- outspent, outworked -- he won by 262 votes out of over 1.2 million votes cast. And then, the day after the election, several thousand absentee ballots mysteriously surfaced, none of them witnessed nor notarized as required by Alabama law, and Sonny Hornsby tried to have them counted. It took a year of court battles before Hooper was finally seated. His groundbreaking victory would not have been possible without the work of many Alabamians -- including a young dynamic lawyer I got to know by the name of Bill Pryor -- and isn't he doing a terrific job. Today -- Today, the Alabama Supreme Court is once again committed to the strict interpretation of the law, led by Justices like Harold See, who's here with us tonight. We've seen -- We've seen similar court reform efforts in Mississippi, Ohio, West Virginia, Michigan, and other states. And, of course, all America saw the popular response to the activism of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in its Goodridge decision -- in its conviction that marriage is "an evolving paradigm." (My wife asked me if I shared that conviction.) Four judges in Massachusetts, by forcing same-sex marriage on an unwilling public and rebuking the legislative power, provoked a national grassroots effort to defend marriage by amending state constitutions and passing statewide initiatives. But the judicial activism about which Americans feel most deeply is to be found in our federal courts. For decades, the American people have seen decision after decision after decision that strikes them as fundamentally out of touch with our Constitution. Let me offer just a few recent examples of a trend I'm confident each of you could explain more powerfully and more eloquently than I can. The Ninth Circuit has declared the phrase "under God" in the Pledge of Allegiance to be unconstitutional, arguing that it is the establishment of religion to require children to recite it in a public school. Earlier this year a federal district court judge dismissed a 10-count indictment against hard-core pornographers, alleging that federal obscenity laws violated the pornographers' right to privacy -- despite the fact that popularly elected representatives in Congress had passed the obscenity laws and that the pornographers distributed materials with simulations where women were raped and killed. Just a few months ago, five Justices on the U.S. Supreme Court decided that a "national consensus" prohibited the use of the death penalty for murderers -- for murders committed under the age of 18. In its decision, the majority ignored the fact that, at the time, the people's representatives in 20 states had passed laws permitting the death penalty for killers under 18, while just 18 states -- or less than 50% of the states allowing capital punishment -- had laws prohibiting the execution of killers who committed their crimes as juveniles. These attempts, and many, many more over the past decades, have led to widespread concern about our courts. While ordinary people may not be able to give you the case number or explain in fine detail the legal principles they feel are being bent and broken, they are clearly concerned about too many judges too ready and eager to legislate from too many benches. Why do ordinary Americans have such an instinctive reaction to judicial activism? I suggest there's an easy explanation: It's called the fourth grade. In the first civics course any of us ever take, we learn about the "separation of powers"-- the doctrine that constitutional authority should be shared by three distinct branches of government: the legislative, the executive, and the judicial. Each has a role, and that of the judiciary, we're taught in the first class we ever have on the subject, is to strictly apply the law and to defend the Constitution as written. The Founders' theory was a simple one: that by dividing power, the three branches of government would be able to check the powers of the others. This separation of powers makes so much sense, even to young minds, because in devising our system of government, the Founders took into account the nature of man. They understood we needed a government that was strong but not overbearing, that provided order but did not trample on individual rights. "If men were angels," James Madison famously said, "no government would be necessary." But men are not angels; and so government is necessary. Mr. Madison and his colleagues did not take Utopia as their starting point; rather, they took human beings as we are and human nature as it is. They believed ambition had to be made to -- to contradict -- counteract ambition. Scholars of American government have pointed out the Founders were determined to build a system of government that would succeed because of our imperfections, not in spite of them. And this was the central insight, and the great governing genius of America's Founders. And in all this the Founders believed the role of the judiciary was vital, but also modest. They envision -- envisioned judges as impartial umpires, charged with guarding the sanctity of the Constitution, not as legislators dressed conveniently in robes. In Federalist 78, Alexander Hamilton described the judiciary as the branch of government that is (quote) "least dangerous" (end quote) to political rights. Because it was to have (quote) "no influence over either the sword or the purse," the judiciary was (quote) "beyond comparison the weakest of the three departments of power." As a result, Hamilton concluded, "liberty can have nothing to fear from the judiciary alone." But Hamilton's optimism has not been borne out. I don't have to tell anyone in this audience that we've traveled a long, long distance from where we began, and from what the Founders envisioned. In the 1770s we saw, within just a few hundred miles from here -- less than a hundred miles from here -- no, just slightly more than a hundred miles -- the greatest assemblage of the political philosophers since ancient Athens. Yet, today, the counsel of Madison and Hamilton and the other Founders too often goes unheeded, at least in influential law schools and among too many of our judges. And this failure has led to an increasingly political atmosphere around our judiciary and increased activism on the part of many of its members. At the end of the day, though, the views of the Founders will prevail because the core defects of judicial imperialism -- including the mistaken assumption that our charter of government is like hot wax: pliable, inconstant, and easily shaped and changed. America's 43rd President believes, as you do, that judges should base their opinions on strictly and faithfully interpreting the text of our Constitution, a document that is remarkable and reliable. William Gladstone called it (quote) "the greatest work ever struck off at a given time by the brain and purpose of man." Not bad for an Englishman. Critics of constitutionalism say it is resistant to social change -- our Constitution. But if the people want to enact or repeal certain laws, they can do so by persuading their fellow citizens on the merits through legislation or constitutional amendment. This makes eminent good sense, and it allows for enormous adaptability. The difficulty for those who do not anchor judicial decisions in the words and meaning of the Constitution is that those decisions are anchored in nothing at all. In the compelling words of Justice Scalia:

said Justice Scalia,

(End quote.) Another defect of judicial imperialism is it undermines self-government. The will of the people is replaced by the personal predilections and political biases of a handful of judges. The result is that judicial imperialism has split American society, politicized the courts in a way the Founders never intended. And it has created a sense of disenfranchisement among a great many -- a very large segment of American society -- people who believe issues not addressed by the Constitution should be decided through elections rather than by nine lawyers in robes. One of the strengths of constitutionalism is that it produces roles -- results that both sides -- all sides -- may not agree with, but which are seen as legitimate outcomes of a fair and free debate. And Constitutionalism offers the promise and possibility of compromise as well. In the words of a recent Wall Street Journal editorial, "the Court has hijacked...social disputes from democratic debate, preventing the kind of legislative compromises that would allow a social and political consensus to form." But this we know: The will of the American people cannot be subverted in case after case, on issue after issue, year after year, without provoking a strong counter-reaction. The public will eventually insist on reclaiming their rights as a sovereign people, and they will further insist that government return to its founding principles. We have seen the Court overreach in the past, in Dred Scott, Lockner and in many other cases, and corrective measures usually follow. We will see one of two things come to pass. The courts will, on their own, reform themselves and return to their proper role in American public life, or we will see more public support for constitutional amendments and legislation to rein them in. It will be one, or it will be the other. Will we see the kind of self-restraint those of you in this room and those of us who work in this Administration want? I believe we will. I say this because we are now seeing the fruits of your good works and the good works of many others. More than 200 exceptionally well-qualified nominees, many of whom have found intellectual sustenance and encouragement from the Federalist Society, have been confirmed as federal judges since 2001 -- not easily, not quickly, but confirmed after a hard effort. On the Supreme Court, we've seen individuals such as Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., who conducted himself brilliantly before the Senate Judiciary Committee. And soon, Chief Justice Roberts will have as his colleague a proud member of the Federalist Society, Judge Sam Alito, Jr. The willingness of these brilliant legal minds to put aside lucrative careers in private practice to serve a greater public good should make us all optimistic and hopeful. Our arguments will carry the day because the force and logic and wisdom of the Founders -- all of them are on our side. We welcome a vigorous, open and fair-minded. and high-minded debate about the purpose and meaning of the courts in our lives, and we will win that debate. In America, conservatives are winning the battle of ideas on almost every front, and few are more important than the battle over our judiciary. The outcome of that debate will shape the course of human events, and the reason we will prevail rests in large measure on the good work of the Federalist Society and those of you in this room tonight. The President is grateful for your support, for your tireless efforts on behalf of constitutionalism and, above all, for your dedication to the founding principles of our great country. Thank you for inviting me, and may God bless America.

Audio source: C-SPAN.org Page Updated: 2/6/23

U.S. Copyright Status:

|

|

|

© Copyright 2001-Present. |