Introductory Remarks by Stanley Hopper: In the late 1940s and early 1950s, I was a very young English instructor toiling away on the awesome task of teaching Freshman English. I was also doing some research. And in this connection I occasionally visited Ezra Pound in that sad period when he was confined under charge of treason and insanity at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington. And one day sitting out on the lawn with Pound and his wife, I turned the conversation from his problems to mine. And I said to him, “What should I, as someone who is trying to say something about writing, what should I stress?” Pound’s reaction was almost violent. He rose from his lawn chair, he shook his fist at the sky, he turned and fairly screamed at me, “Precision, precision, precision, damn it!”

Now, of course, I should have expected this sort of reaction from the old images.

We are assembled here at Drew University to explore together both the necessities for precision and the probable impossibility of attaining it, or least the complexity involved in the communicative process.

I understand that you’ve had an exciting day. There are undoubtedly some in the audience who are inclined to cry out with James McNeill Whistler, “2 and 2 continue to make 4, in spite of the whine of the amateur for 3 or the cry of the critic for 5.” And there are undoubtedly others who protest and will continue to protest any elevation of imprecision or the aura of imprecision to a position of primacy.

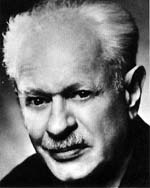

One thing I suspect no one will dispute, and this is the primary idea behind the work of our speaker this evening, that man can best be defined as specifically the symbol-using animal. Mr. Kenneth Burke is assuredly what his friend Stanley Edgar Hyman called him: an utterly scrupulous and super-subtle artist and critic. In a long career as writer, teacher, critic of both the written word and music, and student of man and his ways, Mr. Burke has won the affection and admiration of students of language and of literature everywhere. This is symbolized, I suggest, by his election in 1963 to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His development of what he calls the dramatistic method of studying literary works as symbolic actions has added an exciting element to contemporary criticism. His emphasis on the psychological basis of literary forms, his constant attempt to see old things in new ways, has produced a canon of critical work which makes him today one of the most important figures in American literature and criticism.

We’re proud at Drew University to claim him at least partly as our own, for he has taught and he has lectured here frequently. I happened to be that most unenviable of humans, a dean. And some of my faculty are here, and I hasten to add that as a teacher Mr. Burke is superb and that he has usually managed in his career to have in his teaching w- what most teachers strive for -- the perfect teaching schedule. Malcolm Cowley once described Mr. Burke’s teaching schedule at Bennington College as “every other year, for every other week.”

I can only say to those of my faculty who are here: men, I’m working on it.

A native of Pittsburgh, he was educated at Ohio State and Columbia University. He’s taught at the University of Chicago, the New School for Social Research, Bennington, Drew, and he has lectured widely.

Henry James obviously could not have had him in mind when he penned his celebrated comment on the critic, but he well might have had. You probably remember what James wrote: “The critic is the real helper of the artist, a torch-bearing outrider, the interpreter, the brother. Just in proportion as he is sentient and restless, just in proportion as he reacts and reciprocates and penetrates is the critic a valuable instrument.”

Ladies and gentlemen, Mr. Kenneth Burke.

Professor Kenneth Burke: I am going to try a little bit of an experiment tonight. Instead of just reading this straight through, I’m going to read bits of it and try to introduce some other parts of my theories along with it. I figure you have these papers, and that maybe you might not want to go through them all again.

But I do want to read my kennel: my five dogs. We can set this set-up.

First, there is the primal dog. Incidentally, I happen to come from Pittsburgh and which always pronounces a short-o as an “a-w.” and pronounces an “aw” as an “o.” So, we say “lahn” -- l-a-w-n -- “lahn” -- and we say d-o-g “dawg.” So, I can’t quite get out of that, but I’ll try as much as possible. But I think it’ll always turn out “dawg” in the end.

There is the primal dog. The dog that one usually encounters in a primal scene of childhood. He has a strong unmistakably Freudian strain in his makeup, and he’s crossed with what Malinowski would call “context of situation.” And please do keep watching that notion of situation as it hangs around these terms.

That is, he merges into the background (benign or malign), of which he was an integral part, when the child originally learned to distinguish him. Though both he and his context may have been forgotten in their particulars, the quality of the experiences associated with him may stay with us throughout our lives, figuring subtly (“subliminally” would be the word now) in our attitude towards dogs. And under the influence of drugs, hypnosis, or psychoanalytic couch-work, many particular details about him and his context of situation may be recovered. The main point for our purposes is that he is not properly defined, in terms of his own peculiar nature alone. He is “symbolic” in the sense that an essential part of his “meaning” (both forgotten and unerringly remembered from out the recesses of our past) resides in his role among a complex of conditions not specifically doglike.

I’m trying to suggest that this whole idea of the symbolic element in the Freudian term really involved this notion that it is a part of a context of other elements.

Next, there is the “jingle” dog. Whereas the “primal” dog would be associated with many nonverbal circumstances, the jingle dog would involve his relation to the particulars of speech (such as the fact that in English the word “dog” rhymes with words that the corresponding Hund or chien would not rhyme with; and by a tonal accident that engaged the poet Cummings, who noted that he is “God” spelled backwards). Here also would belong his proper name, plus the punlike relationship to identical or similar names, including those of people or places. One might even extend the range of the “jingle” dog to cover the logically dissociated linguistic situation that unites dog and tree (since each, in its way, has an association with the word “bark”).

That is, the jingle dog is the place at which the world starts to fall apart, but is a very important aspect of our thinking, I believe.

But though the “primal” dog and the “jingle” dog can tug dangerously at the leash of reason, all is quite different with the “lexical” dog, the kind defined in the dictionary per genus et differentiam. Viewed by the tests of either poetry or neurosis, he is an exceptionally uninteresting dog. But without him and his kind, the world of wholesome common sense as we know it would collapse into gibberish. In our civilization, to indicate what the word “means,” you wouldn’t even need a verbal definition, or the corresponding word in some other language. A mere picture of the “lexical” dog would suffice to indicate what was meant, even in a language that we did not know. Yet note, for later reference in this talk: it’s impossible to make a picture just of “dog,” in the specifically lexical sense. For there are all sorts of dogs, dogs of all sizes, breeds, shapes, colors, and so on. But your picture would require you to draw some particular kind of dog, while at the same time your illustration must be interpreted as indicating what is meant by the word “dog” in general. As a matter of fact, the picture in an alien dictionary might have been not of “dog” in general, but of a fox terrier. Also, within this narrower orbit, the same sort of problem would prevail. For even the picture of a fox terrier requires you to use specific traits for general purposes, since all fox terriers differ from one another. Here’s a problem to which we must certainly revert, as regards the questions that have to do with a Theory of Terms.

Many of you happened to have read that other article on “What are Signs of What.” I have a section in there where I very definitively lean on Berkeley for pointing out that aspect of meaning. And that is where I try to work in there this theory of entitlement -- that words are not just looked at as names of things. I get into that further, later. But the point is to keep in mind that it is actually impossible -- a language -- a sentence like, “the man walked down the street,” it is actually impossible to draw a picture of that; because you have to make a tall man or a short man or a thin man or a fat man. You have to make a certain kind of street and so on; and whereas people usually think of sentences like that. That is actually a descriptive.

In my other article, I try to argue that they are really titles for situations. So you want to keep that in mind, related usage.

Fourth, adapting from Aristotle, we’d distinguish an “entelechial” dog, the “complete” dog toward which all doggery variously aspires, to the extent that dogs fulfill their nature as dogs. We here confront the terministic principle involved in an expression such as “perfect” dog, to designate the natural fulfillment of dog qua dog. Obviously it’s much easier for a dog to be wholly a dog (to exemplify the very dogginess of dog) than it is for a human being to exemplify in all fullness the humanity of his nature as a human being. I hope later to make clear how this formalistic principle figures in our thoughts on the functions of terms.

I might just point out, there, the way that works. And I think that you can do it better with a -- well, let’s take another word to get the same principles. Suppose you have the thing “bread.” And then...to correspond to that, after your language has been developed, you can have the word “bread.” Then you can take from that -- along this entelechial point of view -- you can use the expression “perfect bread.” Now whatever "perfect bread" may or may not mean, you can work that from the nature of language. You can have a term that expresses this principle of perfection in it.

Now you notice that you have two different approaches, once you get to the word like “perfect bread.” You can either say that this bread that I have is so poor compared with perfect bread -- and therefore it’s a terrific letdown compared with perfect bread. Or you can say, although this bread is very poor, it represents in principle the possibilities of its perfection. When you get to all those notions that I have later about the way to building terminologies, I’d like to propose that this, I think, is one of the fundamental ones that operates continually, that underlies our modes of thinking.

Finally, there is the “tautological” dog. You get him by crossing the “primal” dog with the “lexical” dog, though this experiment works only if you continue to select among the offspring, not all of which breed true. He should reveal the “primal” strain only in the sense that, like the primal dog, he merges with his context. But he does so in a way typically “lexical.” For instance, it would be a “tautological” step if we went from “dog” to “kennel,” or to “dog food,” or to “dog license,” or to “master, or to “cats,” “hunt,” “game,” "subservience," "loyalty," "running in packs," "doggedness," and so on. When approached thus, from “dog” as point of departure, all such related details become “tautological” in the sense that they are all fused with the “spirit” of the term -- in terms of which they are mutually related (somewhat as though “dog” were at the center of a circle, and all the other terms were distributed along the circumference, as radii generated from this center).

I want you to pass up the next paragraph here on the bottom of page two where I try to bring out another ambiguity about this matter of the contextual aspect of a term, where you can have that, this is the place I deal with in Permanence and Change where the point is you can either consider the dog as the center of a situation or some other aspect of the situation can become the center. And I try to bring out that particular twist there.

But note that, as regards either the “tautological” dog, or the “primal” dog, their definition involves their contextual or situational nature, their meaning as part of a scene. This is the important consideration for our -- our next step.

A little bit more on our dogs and we can move on our way. I think the primal, jingle, and lexical dogs on page three are, I think, clear enough now. I might point out again if the world -- as regards a lexical dog -- had only that, we’d all die of boredom or perhaps bear forth imperialistically to interest ourselves by making other people suffer for our fear of boredom.

Now the entelechial dog becomes of major importance in works of art. For instance, ideally, a character who is to be sacrificed must be the perfect victim for the given situation. The person who is to exact the sacrifice must be, in his way, a perfect fit for his role as victimizer, and so on -- at least insofar as classical norms of artistic excellence are concerned. And perhaps those who spoke in tongues were intermingling jingle utterance with entelechial meaning. If a situation in adult life were capable of being summed up by some analogy (as with the relationship between an anecdote and its moral in a fable by Aesop), the representation would be “entelechial” by reason of its summarizing nature.

The point I want to get there is that when you get types of psychological theory which stress the principle of regression, I think often you can get the entelechial principle stated in terms of some remembered prior scene. In other words, the situation that has a kind of entelechial summing-up can turn into a false memory of a primal scene. And the primal scene -- that would really be the equivalent for this entelechial aspect. And you don’t get that by -- ask me about it more when we get around to the discussion period.

I think that Freud’s concept of a “repetition compulsion” would also fit in here. For such a motive contains “entelechial” ingredients insofar as the sufferer, or subject, almost as though by deliberate design, “perfects” different situations by imposing upon them the same essential relationships. He discussed that in “Beyond the Pleasure Principle.”

Tautological dog. Such associations as one might build up by inert answers to a questionnaire. You’d ask people what they thought of when you said “dog,” and you’d weed out the meanings that seemed idiosyncratic. For your main interest would involve the most representative associations of ideas. Even brilliant stylistic innovators build their figures of speech by not venturing far from such standards of -- standard channels of affinity, though often (as I tried to indicate in Permanence and Change when discussing “perspective by incongruity”) I tried to show how such underlying proprieties of correlation may be contrived by perspectival leaps, as in Friedrich Nietzsche’s style, with its modes of abrupt reclassification, basically a method he could have learned from Spengler or Ezra Pound, had he had the opportunity.

The -- I want to say some more about that as relates to -- in relation to Professor Allemann’s very interesting talk on -- on metaphor. We’ll get that a little later.

Now, what I want to hope to do now is to try to tie in my general position with some of the things that have been said already, and...some of the other speakers. In other words, there’s been many references to dialogue, and I thought instead of just going ahead on my paper, maybe I could make it a little bit of a dialogue by -- by tying in some of my statements of -- of that sort.

Now the -- Professor Brown at one point said, “Everything is symbolic.” Now I want to -- I want to make clear from this -- this notion that I have of symbolic action. You have to get the -- the term as I use symbolic, it would not quite have the meaning that Professor Brown was using there. This – This -- I’m not saying there’s something wrong with it. There’s nothing wrong with his meaning. I just want you to know the one I’m -- I’m dealing with. It’s...a different -- a different -- a kind of situation.

I take it that -- that -- that what you have fundamentally. There’s one place -- put it this way -- there is one place where the relationship between the symbolic and the nonsymbolic is absolutely clear. And that is...if I have a...if there’s a tree. There’s a thing. And then I have a word “tree.” At -- At that point the difference between the word and the thing is...totally clear. The one is a symbol and the other is not.

On that, on simply that level. That is, the one is a mere -- a, a mere use of language. Just think of -- of symbolic action in that sense. Just simply using symbol systems. A tree in that sense is not using a symbol system. So -- So if you will -- if you will try -- start beginning -- start your notion of symbolic action the -- the way I’m dealing with it here, just from that most rudimentary point of view. Other words, that when I am talking here, that’s -- that’s a symbolic act in the sense I’m speaking of.

Now if at the same time it happens to be symbolic, I might be in some way, using gestures or something that -- that happened to reveal something about my character, some, every symbolic in another sense, see? Or it would show maybe some, some particular symptomatic trait that -- in the -- in the psychoanalytic sense. That would also be where you would move this term into a more specific sense.

Now again, I’m trying to think that all these meanings we can -- we can take care of, but let’s see what, we have to get them in their place. The -- So I would say that in...one level that -- that statement “everything is symbolic” would be, you see, would -- would be, not fit this particular case. If, for instance, we imagine this symbol-using animal destroyed all the world, all the objects in the world, all the processes of the world would go on. They could have no symbolic meaning for anybody. There’d be nobody there to have -- to feel that way about them. A tree might be a parent-symbol to you, but it can’t be a parent-symbol if there’s nobody around for it to be a parent-symbol to. And -- and the notion is that – that you – that, that there is just the world of sheer motion which would -- which would exist if all the symbol-using animals were destroyed. And in that sense, the world is non-symbolic. The -- It’s -- It’s outside the realm of symbolism.

Now if, on the other hand, I am a symbol-using animal, then everything that I -- that I do will be approached -- I will approach the world, even the non-symbolic world, through the -- the -- the screens, through terministic screens of one sort or another. And in my use of -- of symbolic action there, by the way, it is not simply reducible just to words. Words are -- are one of the most convenient forms for us to deal with. But it would also apply to the -- to a dance, to music, and paintings and so on. Any -- any symbol system would be -- the use of any symbol system would be an example of a symbolic act.

But the -- now you get in this -- the -- this all comes to a focus in your -- your stress on --on the terministic. Whatever -- whatever scheme you’re working with, you’re working with a set of terms. Music will be in terms of tone and rhythm and so on. And -- And painting in terms of colors. So -- So -- and then of course we have terms in...the sense of words. Then you also have terms of gestures and things of that sort. We don’t necessarily have to narrow the word to say merely the verbal sense.

Now, we -- we can see then how -- how beginning with symbolic in this particular sense that I’m using it, in this most general sense, where --where you would be wrong to say that everything is symbolic. In...the sense that Professor Brown is using it, the word would...also fit, but now we’ve changed our use of it. It’s symbolic there in the sense that once we have a kind of animal that approaches the world through -- through symbol systems, sees it there in terms of those, then -- then everything is going to be approached by that secondary root.

Now...referring to -- to Professor Brown’s brilliant paper, which I would now want to look at terministically, I thought I might illustrate some of my points of view there by -- by just daring to -- to make a few statements maybe of value on it. Along with, I say, in addition to its brilliance, is a – is a -- is what I would call a -- a rhetoric. I would say that – that the speaker from the floor who brought up that point, there is no literal truth , and question that, seemed to me to have a -- a completely basic unanswerable question he caught there. And -- I mean that the -- that is the -- cause you view it, “Is that a literal truth?” You see, there is no literal truth. You get -- when you get a system that’s caught in its own traces, I think that a -- the -- the enemy is the one that is allowed to bring that -- that point out.

Now the -- I remember somebody from the floor also mentioned a fear of the schizophrenic imagery. I think that -- that which I think that was an extremely suggestive point, but it got me to thinking of something else there and that was that -- was there really any obscuring of the line between sanity and madness in the way Professor Brown went -- went about that article? I...submit that...he did not. I submit that the -- that this was a selection of notable, traditional texts, all directed towards a controlled, stylistic, or rhetorical purpose. It involved the use of ideas as imagery, and it -- it was an example of a highly rational procedure, even rationalistically efficient in the choice of texts. And -- and therefore you’ve got a -- an extremely effective, stylistic piece. But I think that you -- you could treat that completely as -- I mean, in other words, once you look at it on a – on a purely terministic basis, I think, there -- there is no -- there’s no problem from my point of view in it at all. As -- As you have a way of using a certain type of -- of imagery or ideas either one using the ideas as images, as using ideas like the notion of abducting the learned ignorance, or the notion of the coincidence of opposites. Or you -- and you -- you can build a whole, marvelously selected work, pieces of exhibits of that sort, and you have a completely rational principle, upon which you base that -- base those choices. And when you get through, you have a very effective rhetorical statement along those lines.

Now, this brings me into this question that I said I wanted to take up in relation to Professor Allemann’s paper, and that is that this whole notion of the -- that Professor Brown was dealing with there -- involves what Professor Allemann called the -- the juxt-opposition of -- of clashing categories. It’s the, two disparate words standing in opposition. Or the essential question is one that aims at the tension which is always inherent the juxt-opposition of two words in the poem. The -- I thought his -- his statement of the various steps in the -- of the -- of the development of the concepts of metaphor was extremely useful. But the...amusing thing from -- from my point of view was that, as I sum my own worry, was that I had, in my Permanence and Change, I had worked out this principle that I call “perspective by incongruity.” And I got this as I explain in the book by analyzing Nietzsche’s style. I got it from , I thought it was – there’s, there’s a kind of a – of a -- a clash of categories that he brought together that -- that -- that produced his style. And I'd never run across that -- that essay of his on metaphor. I don't know [if] to this day how -- [I'd have to] go back and...look it up now. But...his style, I think, had a tremendous amount to do with this type of surrealist perspective that I called "perspective by incongruity."

He called it perspective himself. He used that word a great many times. And what really was -- was the -- as I see it, it involves a -- a taking categories in the mind which you naturally separate as...without thinking. This is in one category and this is in another, and you don’t usually put them together. And then, all of a sudden a lightning flash cuts across there and you bring those two categories together.

A -- A couple of examples that I can give in the -- that I cite there I might mention, don’t happen to have the book with me, but I remember that a -- a range of them in there. And that is that the -- take Veblen’s concept of -- of "trained incapacity."

Now -- now your natural tendency is training is in one category and incapacity is in another. You think of them as -- as mutually exclusive. The -- the whole -- the whole trick here was to -- was to jump those across. Especially where you could speak of incapacity, as -- as training itself as a form of incapacity. And the -- and another one I recall that Elliot used in one place where he spoke of decadent athleticism. Where usually you think of athletics in the healthy category and decadence in another category. But by putting those together, you see, across there, it gives you what I would call a “perspective by incongruity.” And then you can get -- and I think this is the -- the whole essence of the -- the whole surrealist line of -- of breaking down your categories in that way.

I had it among my list of a -- of a -- modes of lining up vocabulary, the remarkable thing is I completely forgot to put that in my list, but I tend to go back and do it on the basis of -- of each statement. And you’ll see that I -- it is -- it worked out at quite some length in the -- in this whole section on perspective by incongruity.

I might just on the side there -- I wanted to -- I thought that there – there is -- I found in working with -- with Shakespeare that there is one other kind of metaphor, and -- and this is merely an -- an aside in this, that works along this line. It’s -- it’s the -- it’s the use of a, variations on a theme. That is, for instance, if you -- in Coriolanus, the work I’ve been dealing with quite a bit lately, in -- in Coriolanus, you have -- the whole play takes place at a time of -- of starvation. These -- these people are revolving under a -- under -- under starvation. And one of the things -- one of the ways to keep reminding the audience of that is to just simply keeping -- keep up references to devouring, to eating, and so on, you see. And -- and the – and -- and there -- there you get a -- a marvelously rational way of -- of just using all kinds of – for -- for accounting for imagery, that will -- that will -- will re-individuate that theme.

The -- the -- now, the -- another one in there -- another simile that works in -- one other metaphor that works very beautifully in there is the whole organic metaphor of the -- of the state. The – the -- Menenius at the beginning of the play uses that whole figure which runs through the classic figure. It’s in -- actually in the -- Plutarch, in -- in his chapter on Coriolanus. And the -- the way it works there, is that the State, the Body Politic, is in disarray. Then the way -- the way to use imagery that keeps that going is to use the analogy from Body Politic to human body, and if the State is in disarray, then -- then you use imagery of...diseased body. And -- you -- the point is there, you’ll notice I think from a low, I think in many modern works, perhaps the, when you move works of imagistic cast, the tendency is proper rightly, I suppose, to -- to start with the study of imagery, but when you work with the -- with -- I think, with any -- any classical texts, I -- I would say that the -- that the -- the imagery should come in last, as you get your situation, your characters, and so on. After you get -- then you -- then you – then you -- then your imagery would be becoming completely rational as a...way of reinforcing all those -- those principles.

Now, going back still now to the -- to this terministic approach to -- to Professor Brown’s statement, I’m going to -- I’m going to take a little chance, even a hunch here illustrates the sort of thing I’m doing, even if it’s proved wrong. And he can tell me whether it’s wrong or not. I noticed that -- that he said -- he spoke of, to put his expression -- “to put an end to politics.” And -- and then I noticed his title, “Apocalypse.” And of course you’re always looking for – for, well, as you would in a dialogue, you’re looking for a post term. And -- and I wondered whether -- whether this was [unclear] an experimental hunch. I wondered whether -- whether it would be good, at least when I read his book, I’m going to keep watching as this were possibility that -- that underlying it -- that it can be -- be reducible to a dialectic, a dialogue, opposing the political to the apocalyptical. And I think it’s a, very possible that -- that would be the -- the design there. I don’t know. He can tell me whether that’s -- whether -- whether I -- I guessed wrong on that. But it doesn’t matter because it gives in principle the -- the way I think you should operate on things like that, because you’re always looking for -- for the possibility of a lineup of terms.

So when Professor Ott cites an author who said, “Opposed to every form of historical positivism is the dialogue,” I maybe noted on the side, here we have at least the makings of a dialogue in that very notion of -- of presenting the dialogue as -- as -- as opposite to the -- to the positivist method. As a matter of fact, I think it is quite possible once you do use the dialogue form, I think it actually is possible to take any system although -- although a -- a -- a -- an experimenter -- a collaborator will usually tell you that dialectic is out, which -- how long is that --- you can certainly analyze his experiment as a -- as a dialogue. In other words, a -- it’s a method of putting questions to nature and getting -- and getting answers from it, which is certainly your -- your -- your -- your proper process there. You get the -- the nearest you can get to a -- to a dialogue with a -- to a conversation with an inanimate thing.

So you get -- so you can -- your basic principle, I can imagine, therefore, a...dialogue made up by having as my two speakers a -- a positivist and a representative of this -- of the position which -- which Professor Ott was --wanted to uphold. Other words, your -- your opponents by a -- a cooperative competition would lead to the transcending of their original level. See, you would get the -- the usual Platonic structure. And I think, which -- which underlies the logic, I think, of the dialogue form.

Now, Professor Ott says that faith is essentially knowledge. Now I put down tentatively here, I -- I -- I’m just simply still trying to illustrate my method. I don’t -- this is not necessarily a disproof. I -- I always say, well, why -- why do we say an act of faith? The -- I -- I think faith is an act just in -- because it’s the -- and then -- and then of course at the end when -- when -- when this -- when faith finally ends up as...centered in -- in the use of language and then that, that in turn, was fulfilled in dialogue, and he said dialogue is life itself. Well, surely life itself is an act. I mean we’ve at least get to act at that point.

So that the -- so that -- that now, at the -- the beginning of your -- of your distinction between the scientistic, or that -- or the approach in terms of knowledge, and the dramatistic, or the approach in terms of action, I think that they’re -- that they’re -- they’re pretty -- it’s pretty tenuous as to which one you go. You can...present either of them at that point. The thing’s not fulfilled enough. I just would point out that, at least from the standpoint of my problem of analyzing -- I -- I started from trying to analyze artistic forms, poetic forms, and so on. I could not approach that in terms of knowledge. I had to approach it in terms of -- of actions, symbolic acts, because of the -- of – of -- well, naturally, this whole position follows along the lines of scholasticism, and act and form are equatable terms. So when I would begin to analyze the -- the -- the form of a work, I...merely just am analyzing the nature of it as an act, as -- as actual processes of development.

Now, you can get the -- the -- the approach in terms of action is not antithetical to the approach in terms of knowledge. The two -- you get to the two eventually anyhow. If I start, but -- but -- but -- but I think that Professor’s Ott’s position should require a stress on -- on action there because the -- the whole point would be that if it is a dialogue, that means that by the act of assertion you organize the enemy or, if you want, the partner, it’s a mixture, it’s a cooperative competition, and as -- as a result of this mutual action, back and forth, you -- you mature the position. And then you can get your knowledge. And all it would – would come as a -- as a derivation out of the dialogue, which is the way I think a -- a Platonic dialogue actually what -- what -- how it’s working. You start out with a group of opponents, partial opponents. And by putting them together, into a -- into a -- a -- a they’re all like -- like rhetoricians -- each one upholding up a partial position -- and putting them all in there, let them mature one another, knock the edges off one another. And the dialogue transcends the -- the limitations of the individual. That’s, I think, your ideal Platonic structure there.

Now, this...terministic stress that we keep always coming back to, analysis of term, the -- it involves in...my case what I mean by logology, sometime I just mean words about words. But...the other special meaning I -- I have for it is a use of -- of theological principles for analogical purposes. In other words, to treat -- to treat theological forms because of their -- of their thoroughness, their development over so many centuries by some of the...most profound minds in our tradition. My notion is that -- that they have carried the resources of language to its -- to its fullest. And what I try to do without any statement of the truth and falsity, judgment of the truth or falsity of a -- of a theological statement as such (something about which I am not competent to make any judgment; I’m not a theologian), I try to -- to use these statements about God as -- or analogically as statements about words. And the simplest notion there is that, I mean, theology and logology, words about God, words about words.

Now, the simplest way to make clear what the -- what the logic of that is -- is how you can go from -- in the theological scheme -- you can go from the word “God” to the secular scheme you can go to the word “god-term.” I mean, you just got the titular word -- the word of the Sum of the Sum -- the sum -- summing-up word, and that will be your god-term even in the most completely secular system. And I -- I submit that sometimes I think that -- that Paul Tillich was -- was -- was really, when -- when he made it almost impossible to be an atheist, if you understand me. What he was really, was working on there was that he just should have gone one more step, and -- and what he, what he was really after, but he still kept the -- the theological borders on it, was really a -- a logological statement, and that -- that -- that there is a sense in which you cannot avoid having a Term of Terms which would be your -- your whole basic structure.

Well, I -- I give the -- in my Rhetoric of Religion -- I give a whole set of analogies there as to how that worked out, and I won’t stop one of those now. But I would like to do, to give one illustration of how this thing works, because of this I think it fits in on this whole matter of belief that -- that we got into as to whether belief is -- faith is knowledge, and so on. I think the old scholastic formula, Credo ut intellegas, “believe that you may understand,” “in its theological application, this formula served to define the relation between faith and reason. That is, if one begins with faith, which must be taken on authority, one can work out a rationale based on this faith, but the faith must ‘precede’ the rationale.”i

Now, the “logological,” or terminologic, or “terministic” counterpart of “Believe” in the formula would be: “Pick some particular nomenclature, some one terministic screen,” (this particular article called “Terministic Screens” is -- is -- is based on that notion, that you have to have a terminology to say anything. Implicit in the terminology there are certain types of conclusions. The most obvious form of that is, if you use a biological terminology, you’re going to get biological types of observations. If you use a...psychological terminology, you’re going to get -- get psychological observations, and so on.

So -- so that the -- the terminology has in it certain ways of directing the attention. And the -- now, my notion, therefore, on this truly logological and terministic level, the equivalent for the word “Believe” is pick some particular nomenclature, some one whose -- you have to talk or something -- use some kinds of terms. Then “that you may understand,” has its counterpart: “That you may proceed to track down the kinds of observation implicit in the terminology you have chosen, whether your choice of terms was deliberate or spontaneous.”

Now you see where we get into where -- where, Professor Ott was talking about this fides implicitas. And there...is the...implicit in the terminology you get the -- the terminology is -- is the logological equivalent of -- of belief. You can’t get around it. And I use an example in...my Grammar of Motives showing how this, you -- you’ll get vocabularies inevitably. For instance, either vocabularies that -- that have a graded series, or -- or else vocabularies that -- that have breaks -- qualitative breaks. And the -- and whichever kind you take, you get a different kind of -- of conclusion just in that. I show how Jung’s terminology of a graded series produced quite a different effect from the kind of terminology you get in Kant because it had breaks between the -- the intuitions and the -- and -- and the concepts and -- and ideas of understanding.

The -- The, if you want, I can, I won't stop on that now unless you think -- you can ask about it if you want to later.

Now, so we have there then, this fits in completely with this logological scheme as the -- the equivalent of fides implicita is the -- is that -- that implicit in your terminology there’s a set of -- of conclusions. Now the -- now what -- what -- how does that follow with your whole idea of terms? The point is that once we get a terminology, we are -- we are set on carrying out the implications of that terminology. And -- and -- and that thing is even carried out to an extent that -- that people who were working on the -- on the atomic bomb, many of them hoped it wouldn’t work! But...the implications are there -- and the -- and it was a compulsion -- it was a terministic compulsion. And my -- my notion there, that every one of our special disciplines today has possibilities of this sort, implications of this sort in it. The choice of that particular terminology is your fides and the -- and the -- the worrying out -- working out of the -- of the observations is your -- is your intelegurer, your...perception as the result of that.

Now, Professor Ott says, “The personal relationship between men is from the outset located in the sphere of language.” Well, I...would rather, just now going along right with that, I would like to add what I -- what I’ve been trying to work on, this notion of man as a symbol-using animal. Can we get that down to an actual, quite feasible, empirical level of -- of statement? And I -- I would propose this. First, I would today -- instead of just saying -- just language, I would have to say the use of symbol systems, in general. A person is an animal capable of muster -- of mastering conventional or arbitrary symbol systems. And get the point. A being who just has a -- who has an instinctive sign language that -- that wouldn’t fit your pattern. But -- but once you -- once you, you get a...type of animal which has to be taught conventional systems, as -- as every one of my tribal idioms is, and every one of our special languages is, that would be your test of...a person.

And another way to approach that would be that -- that you have a -- that you -- you have a second level there. That -- that this is the kind of -- of animal which can -- which can talk about talk, which can make tools for making tools. That second level, a reflexive principle would be another way to approach the same subject.

Now, we get into there the -- the notion of -- of action as literal, not metaphorical. I think I can let that -- we can let that go for a little while and bring up another angle.

[EDITED TO HERE]

Now, the -- so we’ve got another place, I think what Professor McGill said I was very happy to see this quote, but, where he was citing a -- a speaker who said: “None shall speak what he finds right in his own eyes without a foundation of Scripture.” Now there -- now there -- there’s your -- is -- is -- is the -- is the, stated in -- in theological terms again this --this same point I’m making about your -- about your equivalent of that in your logological scheme. You -- you -- you -- you must first have your -- your terminology organized and fit and then -- then from that you will get the equivalent of your -- of your -- your statement.

The -- incidentally I -- I think that Professor McGill also spoke of the power of words which are as strong today as ever, and this is just an aside. But I...would like to argue a – a -- point out one thing. I think that, in my old days, I...was very much affected by Frazer’s idea of the relationship between magic, religion, and science. And one -- one thing I think was completely misleading about that as I -- as I look back on it now, and that is that he always presented magic as bad science. And I think that -- that -- that -- that is a terrifically misleading thing. I mean, there’s a whole -- the whole change from supernaturalism overstressed the naturalistic element and threw out the -- the social element. ...And if you take, instead of looking at magic as bad science, if you look at it as good rhetoric, I think you’ll get much closer to what it was!

I mean, for instance, just imagine what -- what -- what the magician did. The magician worked out ways for a -- a ritual for producing Spring in the springtime and -- and for –and for producing Summer in the summertime. What authority! What authority! Did you ever? Hey! And -- and -- and -- and then, if -- if it didn’t work, there’s where you scapegoat [going 53:17]. “Something’s wrong in the state of Denmark. Somebody’s rotten in this place.” He had the whole thing taken care of. I don’t think this was done by actual scheming. I think it was all just cases where it all fits together rather -- rather happily.

And the -- the -- well, so now -- our -- we -- this thing we get into this whole matter, then what everybody we're talking about keeps running into this [problem] -- in the context of situation. We find that -- that in these situations, are themselves nonverbal. A tremendous amount of that is [unclear 53:51]. You learn language in a -- in a nonlinguistic situation. The -- I try to work out those -- those patterns which I won’t stop on here, except to mention them. And that -- the great -- I think the great terminology -- the terminology of action, that’s your grammatistic, basic terminology, that -- that I -- I didn’t -- when I worked that out in my Grammar, I wasn’t completely methodologically conscious of what I was doing there. It’s all there, but it isn’t -- it isn’t brought out explicitly as I did when -- when my other great terminology of -- or great order, that is, the -- the order set we mean that I worked out in the logic, in my Rhetoric of Religion, the whole set of terms.

The whole point about these is that if you take your key term, and whereas you might think that you just got a whole set of terms connected by “and,” you don’t have anything of the sort. You find that implicit in that key term, peer into it, and you find a whole great family of terms.

For instance, ...in the Grammar, as I would state it now (it’s implicitly there, but not explicitly), say, peer into the word “act” and you see you have to have an agent to carry out the act. Peer into a -- to an agent acting, and you have to have a scene in which he can act. Peer into an agent acting in a scene, you have -- you have to have agencies, means, in order to -- by -- by which to act. And peer into an agency in a scene, acting with means, and it has to be a purpose, or it isn’t an act. It’s -- it’s an accident.

So you have a -- you find the -- then -- then you can see I work on -- go on and develop how the scene itself can have various scope, dimensions. I mean, the scene can be -- can be conceived of in terms of a -- say, a background of -- of a whole pantheon of gods. That’ll be one, then the act will be one sort. This will be what I call a scene-act ratio. Or if -- if you think of it as just one God again, that changes the act accordingly. Think of it as with no god, just in nature, you get a different. Each time you change the nature of the scene, you change the -- the interpretation of the act, because you see the act in terms of the scene in which you placed it.

Now, your -- your -- now your next set is your order group, and that -- and you can spin that: if order, therefore disorder. If order, therefore obedience to the order or disobedience to the order. If obedience, therefore humility. If disobedience, pride. And you get reward and punishment. You can build a whole, great set of terms going from that. I tried to work the -- on the -- on that set in my -- in my Rhetoric of Religion, and taking the first three chapters of Genesis and working from that.

Incidentally, what I did there on the basis of those terms, I -- I always worked on prophesying after the event. And on the basis of my terminology, I prophesied how the -- the first three chapters of Genesis should be -- should develop. And I remember a student once in -- in class got irritated with this, and -- and got up and -- and gave a -- a different interpretation of prophecy as to how the first three chapters of -- of Genesis should develop. And so I said, “Well, let’s look at the text and see!” Whoa! I knew how to prophesy after the event. That’s the – that’s the only good sound way to prophesy on these matters!

So -- then you -- but then -- then you got your -- your power family, and I have a -- a section on that, and then I -- I think that -- that -- and I had some -- some slight indications of it. No, I don’t think I deal much with Freud’s notion of the basic equation of a -- what you get from spinning the idea of repression as an unconscious process. When you see there’s a whole -- see how -- how a group will spin from that. If repression, therefore something repressed. Something to do the repressing, something to get it, something to avoid repression, some kind of energy to. You get a whole set of -- of terms implicit in that. And in the same way, if unconscious, then conscious, and a possible word between the two. Same as if you have God and man, you get a term God-man in between.

And you have all kinds of ways in which you can spin your -- your -- your terminology along those lines.

Well, I would -- I would just say one thing more on that, and that is that your -- your -- there’s a great -- I’ve -- I’ve showed -- I’ve showed in -- in the text there a great number of different ways in which you can line those -- those notions up.

My -- the first -- the first thing that makes you feel bad is, well, could I put them all into one -- under one head? But, I wonder, the next thing I thought of is, no, that -- that -- this is the source of freedom right there, precisely because you -- you can’t imprint upon the human mind just one of these ways of lining up a set of terms. And that in itself is enough to keep things moving around. And the -- and when -- when Professor Ott quotes -- likens Bonhoeffer’s thinking to -- to Heidegger’s saying, thinking is being restricted to one single thought, which stays in the heavens like a star, I -- I -- it’s -- I would tie it in with -- with -- with my notion in there, that the way you get -- once you get a cluster of terms like that -- the -- you’ve got to set the -- just the way you have it in the heavens and the star, as from each one looking out at the others, you get a -- you get a totally different perspective on the whole scheme. And then he only goes on and says that the -- the dialogue partner A will probably lift the particular utterance of B out of its actual context, which is for him alien and hard to understand. And he will for the time being hold to this affirmative alone.

I -- I suddenly see the -- the kind of way in which the individual, even a -- even in a -- in a dialogue without a person had his own individuality that comes through there, even when they are working together. He can bring -- he can see it, then, from this one angle, and spin -- spin from that term. Just the same, as for instance, if you’re working with the order series. You might -- you might spin -- you might spin the whole thing from looking at all from the standpoint of obedience, you see. Or you might look -- look at it all from the standpoint of -- of punishment. Or -- or -- and so on.

But -- but each time there – there – there is, like Stations of the Cross or something. Each one -- you -- you meditate from each one, you’ll get a different picture of the others, even though they’re all -- even though they’re all involved.

So I would take this as my, as my basis, on a purely logological basis, of the -- the argument for -- for the -- the principle of freedom. You -- you can -- you can take a man who had a -- who had a terminology, and as -- as long as you got all that [terrific] vibrancy and pliability among terms, each one being a perspective on which you can built up a whole scheme, I -- I think it's -- it's almost impossible to -- to make people behave and get them really settled once and for all on one of those notions.

Now, the -- there’s one other that I would want to stress before we get to -- to our close here near the end. The -- the power family is a particularly muddlesome one. I give a -- a long set of tentatives when I first ran across, it is in -- in my preface to my Philosophy of Literary Form. But the -- the point is basically and -- and it gets down to this, from the standpoint of our current difficulties, and that is this distinction between action and motion. Your -- your -- your -- your -- your -- your power group, basically the strongest place in the power group is in the motion category. I mean, for instance, the -- the things like the -- the -- the energy, the bomb, the chemicals, the -- the, and -- and even if a person who has power in the -- in the -- in the action category. I mean in -- in – in the matters of -- of political authority or something like that. In the last analysis, they are again -- the power is not really implemented until he can back it up with the motion category. He -- he has to have powers there in the purely physical sense to -- to back his authority. So that the -- now the – the -- the big point here that I run across in this whole matter of trying to analyze this notion of symbolic action, with the Charybdis on one side, of its moving purely over into the notion of symbolic action in the psychological sense, which I would call symptomatic action. And I -- I’m not objecting to that at all. I’m just saying that we’ve got to have this main meaning first.

And then over on the other side, the sort of thing you get from a computer. I find it -- I -- I -- when I try to dodge the -- the -- the Freudian thing, I run over into the computer on the other side, and I -- I’m trying to make a line right between those. And I think that the -- that the -- the way that we do it, I think, you can avoid the computer, is on this matter of a principle of the distinction between action and motion. That is, the man who invents that computer is acting, he’s a person and he acts. And -- and -- and -- and the computer can but move.

And...there is your distinction between things and persons. And -- and now my point is that -- that for a long time, when I used to use this dramatistic perspective, I used to accept it as a -- as a -- as a -- a figure. I myself would talk -- talked about it as a metaphor. Well, I’ve got my price on it now. I think it’s literal. It’s actually literal. And here’s the way you can -- you can -- you can do that. You don’t start with the dramatistic element. You start with -- with the notion of action. It is just as literal to say that people act as it certainly is to say that they’re merely machines. That it’s -- it’s -- it’s at the very least -- it’s like -- it’s like James’s will to believe. I mean, you got to choose one or the other. And the -- and -- and you certainly relate to one another. Your -- your -- your intuition -- the intuition on which you’re related to one another is certainly the pragmatic notion that you treat people as -- as people. You don’t treat them as machines. And even the behavioristic psychologist, even though he might use a terminology of that sort to reduce his experiments, he does not treat his own -- his own family and...associates in -- in such terms.

So -- so that, I would say -- that the -- that -- that the -- that the mechanistic metaphor is really -- is the metaphor. And now I would say that people do act. And now, and I say that -- that – that the -- that -- the equipment for acting is, of course, this business of being able to -- to master symbol systems in the way I said. That gives me my -- my empirical backing for that -- what I mean by that. I mean, it isn’t just merely a -- a assertion. Remember they were the kind of people who could learn these arbitrary conventionalized symbol systems. And that would be the -- the test of the kind of person who could act against what the -- a mere thing can do.

Now the -- and now, if you want, oh, if have also -- you begin to worry that machines have -- also have this possibility to work with a lot of that stuff. You have -- you have another -- you have an out there, too, because remember, that the -- the person is an animal, and a machine is an artifact, and so you have to -- when you get -- you get the kind of -- of instrument which is using a terminology, which also has the power of...the susceptibility to pleasure and pain. And one of the -- the most -- most remarkable things about this whole use of the computer in the -- in the cult of the computer now to analyze people, as though it were an adequate model, is the fact that you have -- you’ve left out the most essential thing in all about a human being, and -- and -- and its -- its ability to -- to -- to suffer or be happy. A...computer can’t laugh. It can’t cry. And how could this be a model for a human being?

So your notion is that although -- although actions require motions -- you can’t act without moving -- you can have motions without action. And that’s your -- that’s your fundamental formula there.

Now, there are the temptations to be an automaton. That is, there are temptations whereby the -- the most noble -- one of the most noble traits we have -- the notion of obedience, can make us act rather as -- as conditioned cattle, and so on.

Now the -- the -- there’s a chapter I’m omitting there that was this chapter on the thing -- on the written word. I’d just like to bring out just a point I have on that, and then we’ll finish up. The point I’m getting at there is that people don’t seem to realize the difference between the -- a...piece of writing and a painting, let’s say. A...painting, the performance is right there in front of you. That’s the performance. The -- a -- a piece of writing is instructions for performance. And -- and in that sense, a piece of writing is like, also like -- like a piece of music. A piece of music is instructions for performance. And -- and people don’t really realize, they -- they know they can’t play the piano or something. They don’t seem to realize that -- that it takes just as much skill to read a page as it does to -- to -- to read a musical score. And -- and -- and that the same sort of thing is -- is operating. That neither of them has to meet the test of a purely sensuous element in itself as you get in a painting and so on. And -- and that, because of this fact, that it is not the performance, but the intermediate stage of the instructions for performance.

But let me just close in on these -- these two, three quick points and then we’ll be done. I would in -- in the -- the -- I said, the -- the highest, I think the ultimate terminologies come to a head in the -- as you find them developing in structures. You get this one, your dialogue comes to a focus in the -- in the notion of transcendence, the -- the -- the Platonic transcendence. I think the old battle between -- that Plato had with the tragic poets is that -- this goes on and we -- we -- what is it, is it transcendence or is it catharsis?

And I just read just enough of this section on the -- on the -- on the transcendence theme to get the point. This -- this leaves -- this gives you two -- two points of view -- one idealistic, one promissory, and the other one, rather troublesome. And I can sum them up rather close -- quickly. I use the “Dialectician’s Hymn,” something I wrote to give the point there. Then -- then the notion is that if man does approach everything through symbols (and, of course, the Logos is the ideal term summing-up that sort of an approach), then everything will be for him in some way or other inspirited with the Word. So that then -- that gives me my way of tying in the -- the dialogue, so I finally get a world all symbolic, as is, even though I started with this very distinction:

Hail to Thee, Logos,

Thou Vast Almighty Title,

I might say before I go into this -- that the -- at the end of this, there are two perfectly -- two heavy words. One’s synecdoche and the other tautology. I use synecdoche to refer to the part of the whole, and tautology just to refer to the fact that if -- if something is -- is infused with a -- with a generative principle, the same principle will -- will be present in all the parts.

Hail to Thee, Logos,

Thou Vast Almighty Title,

In Whose name we conjure--

Our acts the partial representatives

Of Thy whole act.

May we be Thy delegates

In parliament assembled.

Parts of Thy wholeness.

And in our conflicts

Correcting one another.

By study of our errors

Gaining Revelation.

May we give true voice

To the statements of Thy creatures.

May our spoken words speak for them,

With accuracy,

That we know precisely their rejoinders

To our utterances,

And so may correct our utterances

In the light of those rejoinders.

Thus may we help Thine objects

To say their say--

Not suppressing by dictatorial lie,

Not giving false reports

That misrepresent their saying.

If the soil is carried off by flood,

May we help the soil to say so.

If our ways of living

Violate the needs of nerve and muscle,

May we find speech for nerve and muscle

To frame objections

Whereat we, listening,

Can remake our habits.

May we not bear false witness to ourselves

About our neighbors,

Prophesying falsely

Why they did as they did.

May we compete with one another,

To speak for Thy Creation with more justice--

Cooperating in this competition

Until our naming

Gives voice correctly,

And how things are

And how we say things are

Are one.

Let the Word be dialectic with the Way—

Whichever the print

The other the imprint.

Above the single speeches

Of things,

Of animals,

Of people

Erecting a speech-of-speeches—

And above this

A Speech-of-speech-of-speeches,

And so on,

Comprehensively,

Until all is headed

In Thy Vast Almighty Title,

Containing implicitly

What in Thy work is drawn out explicitly—

In its plenitude.

And may we have neither the mania of the One

Nor the delirium of the Many—

But both the Union and the Diversity—

The Title and the manifold details that arise

As that Title is restated

In the narrative of History.

Not forgetting that the Title represents the story’s Sequence,

And that the Sequence represents the Power entitled.

For us

Thy name a Great Synecdoche

Thy works a Grand Tautology.[ii]

Now, I would like to -- now I would like to end with the -- the one, the mean one. You see, if action, unfortunately if action [unclear: I want to end but -- I will end in 1:13:08] beyond a couple sentences. If action, then drama. If drama---that’s -- that’s the perfection of action, that’s the perfect form of action. If -- if drama, then conflict. If conflict, then victimage. So this is the threat -- the -- the scapegoat that always overhangs us, as against a happy, what I think, we just dodge between these two solutions all the time. It’s this ideal climb, Platonic climb, and then this -- this one -- all the purification by goat.

And I use here, to bring out the quality of -- of this notion, I bring out, I analyze Coriolanus’s play from this point of view. I mean, the play of Coriolanus.

Take some pervasive unresolved tension typical of a given social order (or of life in general). While maintaining the ‘thought’ of it in its overall importance, reduce it to terms of personal conflict (conflict between friends, or neighbors of the same family). Feature some prominent figure who, in keeping with his character, though possessing admirable qualities, carries this conflict to excess. Put him in a situation that points up the conflict. Surround him with a cluster of characters whose relations to him and to one another help motivate and accentuate his excesses. So arrange the plot that, after a logically motivated turn, his excesses lead necessarily to his downfall. Finally, suggest that his misfortune will be followed by a promise of general peace.[iii]

Now, just one last thing and we will be through. The -- the end with my -- the last of a section of my -- oh! got the wrong one here, haven’t I? Well, they, oh here it is. Maybe they didn’t want me to do it. Here, the Fates, the Fates.

By way of parting,

Let’s dwell on a simpler thought, of this sort:

In the world as we know it, there are many kinds of conferences, consultations, symposia, and the like. Usually, somewhere in the course of them, participants fall to bewailing the inadequacies of speech. Yet, but for speech, any such enterprises would be almost impossible, even as regards meetings of experts in other forms of symbolic action.

For a parting sunshine thought, let’s look at the matter thus:

Think how happy each one of us is, whenever he chances to say something, even if it be but a single sentence, that someone else agrees with. And if we are outright praised for our offering, we swell with pride (though usually hastening to adopt a measure of what Marianne Moore has astutely called “judicious modesty”).

Just then -- just think, then: What if, far beyond the presenting of our tiny inventions, we had invented the realm of words itself. How we would love ourselves!

The thought might help remind us how greatly we do prize that miraculous medium, The Word. And if I may quote from a former dear friend of mine, whom I also necessarily broke with (for how could one but break with someone to whom one has been so close?):

There is peace in the sequence of changes fittingly ordered: vegetation is at peace in marching with the seasons; and there is peace in slowly adding to the structure of our understanding. With each life the rising of a new certitude, the physical blossoming free of hesitancy, the unanswerable dogmatism of growth. Who would not call all men to him -- though he felt compelled to dismiss them when they came, communion residing solely in the summons.[iv]

Thank you.

It wouldn’t much matter what my preference is. My notion is that the -- that the -- I think the two methods are -- are just the two we’re going to go on with as the -- I think that people are, for one thing, the -- the Upward Way, the – the -- the Platonic Climb, I think it’s intrinsic to the nature of language. So that’s -- that -- that fits in for, pretty well with a -- as a part of our nature. And we’ll go on with that. And -- and then we get this notion that I referred to earlier, that -- that -- that is the difference between your idea, your perfect solution, and the thing you had. Is it -- is it -- is it treated then as the -- as a -- as a mockery of the perfect solution, or as containing the perfect solution somewhat? It would be that. You’d have that.

And the other one, I think, is moved more on the -- on the -- perhaps on the merely physical level, and that is, the -- the fact that the human body was -- was so -- over so many centuries has been adapted to strain that I question whether -- whether we can ever -- we can ever quite resolve a -- a situation of comfort. And I think the -- I think we -- we just -- I noticed there’s a -- I just got a letter the other day from a man that’s down in Washington who is doing some -- some studies in stress-seeking. And, or they -- they’re taking stress as a -- as a basic purpose in -- in certain types of -- at least, certain types of personalities. Now, so that, certainly this is -- this is true in the -- in the case of stress-seeking in the -- in the realm of -- of the imagination. Whether -- whether we -- whether we watch too much in -- in actuality or not, certainly the -- the -- the basic way of entertaining people is to take a -- a problem in the -- in the -- in the practical realm, something which is an unresolvable problem, and transform it into a form of entertainment in -- in drama and poetry.

So it’s -- that’s the nearest we can get, it seems, to a -- to a resolution of this. But the -- I think in the -- I think there will always be the tendency for people to -- to carry out these stress elements.

As a matter of fact, I -- one of my -- this is merely a -- a -- an amateur suggestion, and I can’t prove at all, but -- but I -- my notion is that -- that a great deal of the -- of the so-called juvenile delinquency today, I -- I think is due to the fact that the -- that the conditions of living in ordinary circumstances do -- do not put enough strains on -- on people of a -- of a -- of a natural nature. I mean the -- the strains of the -- the sort of strains that were -- that were natural under -- under conditions of -- of -- of simple primitive living, the kind of strains, say, an Eskimo gets, and what he has -- what he has to put up with in the winter, things of that sort. Where -- where you get -- where you get a whole situation where -- where -- where so many -- where -- where in -- in a natural condition, man didn’t have any problem about -- about the morality in these larger dimensions. The -- the situation itself compelled him to develop a tribal life which -- which -- which was feasible, was viable -- viable. And I think as -- as you get into -- into this conditions of arbitrary living, that -- that particular type of -- of natural response is -- is confused. And it takes a tremendous amount of -- of new types of imagination and new types of -- of conscience, and so on, to -- to make up the difference with those things.

So, as far as I see, the -- the two things are -- are just with us, whether you like them or not, are just in this fact that the -- that the act -- the act does lead to the enemy. And as a matter of fact, the -- it’s the -- it’s about the only way that -- that people ever get together. As I -- as I said, the -- the most bitter way to say this is congregation by segregation. I think it is -- is one of the most terrifying things about this bloomin’ human animal, but I think you do -- you do find it working again and again, and a building -- building up some kind of -- of union by -- by an enemy in common. And it’s questionable whether -- whether, at least, if we do get, I think it is a continual temptation of a human being, in that, and even in the attempt to get around it, will themselves be a great kind of strain with a -- in a -- of a -- of a highly moral nature.

Tell me what’s wrong with --

Can he pick a fight, yeah, huh? All right. Well, I guess I can go home?

<Audience Question> Mr. Burke, can you

comment on your notion of drama as the perfection of action?

Oh. Yeah. Well -- well, this is my -- this

is my -- my notion of the -- this is -- this -- this whole entelechial

principle. I might -- my notion is that -- that the -- that the

principle of perfection is a -- is a fundamental motive in -- in -- in

the human being. It’s my definition for man might bring this out, and

man is the symbol-using animal, inventor of the negative, separated from

his natural condition by instruments of his own making, goaded by the

spirit of hierarchy, and rotten with perfection.

Now, the -- the point is there -- is the -- the way that shows up is the -- is in the attempts to -- to find a perfect enemy is the way it shows up most. I mean, for instance, the whole -- the whole -- the whole Hitlerite scheme is an example of that, trying to make the -- the Jew the perfect enemy, giving them every vice you could, you see. To make it be, the irony of perfection, and turning it into this -- this other form. And whenever you get -- and -- and you find that -- that tendency turning up continually in the -- in that. Now, this -- this is your – this -- this is your principle of -- of conflict.

And my notion is -- here’s -- here’s the -- here’s the way to get at this. If I take -- if I take my -- if I say that -- that action is a literal, people do literally act, I make that, now -- now how do I get my -- how do I get my -- my model? Well, see, action is your fundamental category in -- in Aristotle’s Poetics we were discussing, the drama. Now, my -- my -- my -- now I find -- by taking the drama as my model, I can now find what kind of -- of other terms are implicit in the idea of an act. And I’ve got [unclear 1:25:43], I’ve got choice, and -- and, of course, in -- in the -- in the -- in the drama is -- is -- is the -- is the course, in the Aristotelian drama, is the -- is again the principle of the -- of a victim.

And, of course, the same -- the same principle is in -- is in the -- is in the Aristophanic comedy -- comic goat instead of the tragic goat. What your -- your -- your drama is your -- is your -- is your perfect form of an act. And -- and therefore, and then look into it and see what you’ve got. And you can’t get it without -- without this principle of -- of conflict then, and the cleansing through the -- through the sympathetic or antipathetic relations to the -- to the chosen victim.

<Audience Question>: . . . Take Measure for, Measure for Measure. Here’s the, here’s the plot of the king who goes down into the cognito, and exposes the disorder in the city. And then he comes back, and he has this victim, but he – but he pardons – pardons the victim. And the play ends in the – the marvelous Shakespearean charity – charity. Does this have any reference to the – to the ways what you’re taking – talking about here?

There are -- I think the -- I think the -- the best example, of course, is in Midsummer Night’s Dream where they -- when you get the -- all the principle of victimage is -- becomes eliminated finally. I think in the -- in the Measure for Measure, as I -- as I interpret that play, I see it -- I see it this way, that the -- that the -- what Shakespeare does there is somewhat like -- like what he does basically -- the way he uses his situation. It’s somewhat like in the -- in Othello, that is -- the -- the -- he -- he -- he, in all sorts of ways, he -- he uses the -- his villain to point up the -- the vices of the -- of the public. Now, it’s the -- it’s the villain’s fault, but all he’s doing all the time is -- is titillating the -- his -- his audience. And I think it’s the same thing that -- that -- that -- that you get in the -- in the -- in this -- in Othello, where the -- where -- where things carried out completely.

But the -- but the -- you’re -- you’re -- you’re right that the process there is -- is not wholly resolved in -- in the sense of -- of an actual killing of a person. But -- but -- but I don’t think -- as -- as -- as -- as Racine points out, the victim does not necessarily have to be a -- a kill. A -- a -- as your principle of sacrifice is the -- can be taken in many forms. The fundamental notion is there, you can get that from another angle, too, but as from the -- from your principle of order. It -- it -- it being order, you -- you have to adapt yourself to order. You have -- there has to be a sacrificial principle to adapt yourself to an order. And then you get the -- the coming in from that angle either -- either through, it’ll either show up as -- as homicide or as suicide. And my notion is that -- that where you have an outside victim, then -- then -- then you -- then the other way, but -- but otherwise, people who do not victimize that -- that way -- then conscientiously they develop ulcers or something like that -- get psychogenic illnesses -- which is a much nobler form of victimage, but not so comfortable for them.

<Audience Question>: There would seem to be some direct correlation between your comment on man, need for [unclear] action, and Norman O. Brown’s concept of polymorphous perversity. Could you comment, please, on that.

Well, I -- I -- I do agree that I think that -- that when you get the -- well, one of the -- one of the modes of -- of -- rebirth in a person, who is -- who is -- who is an appointed victim, particularly in -- in -- in types of -- of work where you get a conscientious person who -- who deliberately imposes rituals of -- of rebirth upon himself by ritual regression, I think you -- you will -- you will get, as a part of it -- the -- all of our symbolism of -- of your polymorphous perverse element.

If you’re going to think of it, I would -- I would point out about the whole polymorphous perverse notion, you got to watch this two ways. I have in another section of -- of this work which is not here in that, I -- I point out that -- that -- that there’s one -- there’s one principle in Freud which, although it may -- I don’t ever claim to be competent to -- to deal with this -- these matters on the -- on the -- on -- on the medical level. I can only deal with them on the -- on the -- on the basis of my -- notions of my terminology.

I would point out this that -- that Freud has what I call a principle of dramatization in his -- in his scheme, and he works it like this: that any time you -- you -- you have a -- two things, and let’s say -- let’s say you -- you resent somebody. Well, the way -- the way you have that -- you have a double principle in there. First, you want to kill him. Then you attenuate that, sublimate that in the sense that you might even try to be nice him, you see. That -- that -- that is the -- or -- or you -- you’re -- you’re -- you’re affectionate to somebody, well then it’s either -- it’s either incest or -- or homosexuality, or something like that, which is then attenuated, you see.

As he -- as he -- both -- both schemes -- first puts in this element, and then takes it out. I point out in my -- in my Grammar of Motives how that worked in the case of the -- of the Oedipus Complex, where -- but that adapted at some point that -- that the way I’ve analyzed the whole notion of the temporizing of essence, but what it gets down to is something like this: Once you have a -- a narrative terminology, you’re understanding essence in terms of -- of a time sequence. The way you say that something is such-and-such in principle is that you say it -- that’s the way it was the first time.

So in my -- in my analysis of -- of my chapters in Genesis, and I -- I try to show how, the narrative way or mythic way to say that man is, in principle, a sinner. You’ve got that word “principle” which is -- has an ambiguity, either temporal first or narrative or -- or logical first. The way you say man is in principle a sinner, you -- you say the first man sinned. And the -- now in the same way, when -- when -- when Freud -- Freud fell into that in -- in -- in the case of his -- his notion of the primal crime. That is the -- if the – the -- the -- what you have on the purely, just here and there, right -- right in front of you, is -- there are certain conflicts intrinsic to a family structure. That’s what you would have without this -- this narrative trick getting in to it.

See, the nineteenth century was so -- was so full of historicism in an uncriticized sense. They nearly always turned things into a -- into a temporal fact, and it was particularly susceptible in German, because that wonderful word “ühr.” I don’t think you’d be an ühr-something. And -- and – oh yeah – and – and the -- so that the -- now -- now the -- the – the -- the whole point there is, the way you would say the words of -- you can just look at the family, there -- there’s certain conflicts intrinsic to a family. No, that isn’t the way you do it. You would say that there was a -- there was a ühr conflict, there was a primal conflict in -- in the -- in the -- in the farthest conceivable past, and then that is attenuated, see. It came down. But though he first gives you this -- this wonderful dramatic intensity, and then qualifies it by this -- by this principle of attenuation.