[AUTHENTICITY CERTIFIED: Text version below transcribed directly from audio]

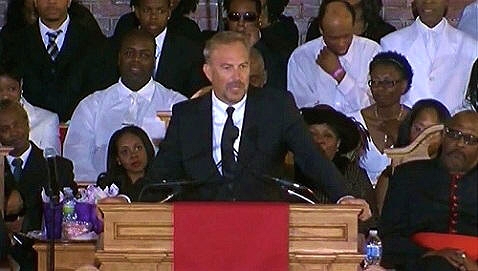

I’d like to thank Cissy and Dionne for the honor of being here, for everybody in the church treating my wife and I so gracefully. I'm going to say some stories, maybe some of them you know; maybe some of them you don’t. I wrote them down because I didn’t want to -- I didn’t want to miss anything.

The song "I Will Always Love You" almost wasn’t. It wasn’t supposed to be in the movie. The first choice was going to be "What Becomes of a Broken Heart,"1 but it -- it had been out the year before in another movie and we felt that it wouldn’t have the impact, and so we couldn’t use it.

So what becomes of our broken hearts?

Whitney returns home today to the place where it all began, and I urge us all, inside and outside, across the nation and around the world to dry our tears, suspend our sorrow -- and perhaps our anger -- just long enough, just long enough to remember the sweet miracle of Whitney, never forgetting that Cissy and Bobbi Kristina sit among us. Your mother and I had a lot in common. I know many at this moment are thinking, "Really? She’s a girl -- you’re a boy. You’re white -- she’s black. We heard you like to sing, but our sister could really sing."

So what am I talking about? Kevin Costner and Whitney Houston, they don’t have anything in common at all. Well, you’d be wrong about that. We both grew up in the Baptist church. Wasn’t as big as this. My grandmother played the piano, and she led the choir, and her two daughters, my mom, and my aunt both sang in it. The rest of my family, uncles, aunts and cousins, sat every Sunday out front and watched.

My earliest memories are tied to that old church in Paramount. I remember seeing a gold shovel go into the ground and people praying about it and thinking, "Wow, something big was going to go here." And I watched my father and the rest of the men build it from the ground up. I was probably four years old and seemed to be always in the way. I wanted to help. I wanted to be in on the action. One of the men snapped down a red line where the choir would be standing one day and said, "Have at it," as many nails as you want all in this line. I always took great comfort in watching my mom and aunt sing, knowing that they would never fall through that floor where I had worked.

The church was the center of our social life and Whitney and I would laugh, knowing it was also the place where you could really get into big trouble, especially when you were allowed to sit with your friends and not your parents in the big church. I remember more than once being pulled from the pew for whispering and passing notes. I don’t believe my feet ever hit the floor as my father hauled me outside in front of everyone. I believed even the preacher prayed for me.

Whitney’s favorite story of mine was me sneaking into the church kitchen after communion. I liked the little glasses of grape juice that were left over. I liked how they felt in my hand. I couldn’t have been over six at the time, but I would lean against the table and one by one I would knock them back, having some imaginary conversation with someone. My father was the one who found me, and again, asked me what I was doing. I told him I was a cowboy and that I was drinking whiskey. I don’t think my feet touched the floor that day, either.

It was easy for us to laugh. The church was what we knew. It was our private bond. I can see her in my own mind running around here as a skinny little girl knowing everyone, everyone’s business, knowing every inch of this place. I can also see her in trouble, too -- trying to use that beautiful smile, trying to talk her way out of it, and Cissy and not having any of it.

Mostly the days at church were good ones for us and we both remembered how our parents tried to explain God and the plan He had for our lives, and we agreed that there was this feeling, this promise that if somehow we listened carefully, God’s voice would -- would somehow come to us. I told Whitney that I always worried God was going to ask me to be a preacher. I wasn’t sure how much fun ours had. Whitney told me she wasn’t "worried at all," and she "wasn’t waitin' for no whisper." She told God that she was going to be like Aretha, like her famous cousin Dionne, like her beautiful mother Cissy.

There can be little doubt in this room that she has joined their ranks and as the debate heats up this century -- and it surely will -- about the greatest singer of the last century, as the lists are drawn, it will have little meaning to me if her name is not on it.

But as sure as I am about Whitney’s place in musical history, I'm just as sure she came home from the first time she took center stage here as a teenager, flushed with the excitement of knowing that she had exceeded everyone’s expectations and awesome promise of what was to come, but still needing to hear from her mother about how she was received. Was she good enough? Could I have done better? Did they really like me? Or were they just being polite because they were scared of you, Cissy? These are the private questions that Whitney would always have, that would always follow her.

At the height of her fame as a singer I asked her to be my co-star in a movie called "The Bodyguard." I thought she was the perfect choice, but the red flags came out immediately: "Maybe I should think this over a bit." I was reminded that this would be her first acting role. "We could also think about another singer," was a suggestion. Maybe somebody white. Nobody ever said it out loud, but it was a fair question -- it was. There would be a lot riding on this. Maybe a more experienced actress was the way to go. It was clear: I really had to think about this.

I told everyone that I had taken notice that Whitney was black. The only problem was, I thought she was perfect for what we were trying to do. There was a bit of a relief in the room when we found out that Whitney was going to be on tour and she wouldn’t be available for our movie. The anxiety came right back when I said "We should postpone and wait a year."

That was a lot for the studio to accept, and to their credit, they did, but not without a screen test. Whitney would have to earn it. That was the first time I saw the doubt, the doubt creep into her that she would not be handed the part. She would have to be great. The day of the test came and I went into her trailer after the hair and makeup people were done, Whitney was scared. Arguably the biggest pop star in the world wasn’t sure if she was good enough.

She didn’t think she looked right. There were a thousand things to her that seemed wrong. I held her hand and told her that she looked beautiful. I told her that I would be with her every step of the way, that everyone there wanted her to succeed, but I could still feel the doubt. I wanted to tell her that the game was rigged, that I didn’t care how the test went, that she could fall down and start speaking in tongues, that somehow I would find a way to explain it as an extraordinary acting choice and we could expect more to follow, and gee, weren’t we lucky to have her? But -- But that wouldn’t have been fair. It wouldn’t have been fair to Lawrence Kasden who had written the screenplay 15 years earlier. It wouldn’t have been fair to my partners at Warner Brothers. And it wasn’t the right signal to send to Whitney.

She took it all in and asked me if she could have a few minutes by herself and would meet me on the set. I was sure she was praying. After about 20 minutes later she came out. We hadn’t said four lines when we had to stop. The lights were turned off, and I walked Whitney off the set and back to her room. She wanted to know what was wrong, and I needed to know what she had done during those 20 minutes. She said, "Nothin'" in only a way she could. "Nothin'". So I turned her around so that she could see herself in the mirror and she gasped. All the makeup on Whitney’s face was running. It was streaking down her face and she was devastated. She didn’t feel like the makeup we put on her was enough, so she’d wiped it off and put on the makeup that she was used to wearing in her music videos. It was much thicker and the hot lights had melted it. She asked if anyone had seen -- anyone had saw. I said I didn’t think so. It happened so quick.

She seemed so small and sad at that moment, and I asked her why she did it? She said, "I just wanted to look my best." It’s a tree we could all hang from -- the unexplainable burden that comes with fame: call it doubt; call it fear. I’ve had mine, and I know the famous in the room have had theirs. I asked her to trust me and she said she would. A half-hour later, she went back in to do her screen test and the studio fell in love with her. The Whitney I knew, despite her success and worldwide fame, still wondered, "Am I good enough?" "Am I pretty enough?" "Will they like me?" It was the burden that made her great, and the part that caused her to stumble in the end.

Whitney, if you could hear me now, I would tell you you weren’t just good enough, you were great. You sang the whole damn song without a band. You made the picture what it was. A lot of leading men could have played my part. A lot of guys -- lot of guys could have filled that role. But you, Whitney, I truly believe were the only one that could have played Rachel Marron at that time.

You weren’t just pretty. You were as beautiful as a woman could be. And people didn’t just like you, Whitney. They loved you.

I was your pretend bodyguard once not so long ago, and now you’re gone, too soon, leaving us with memories -- memories of a little girl who stepped bravely in front of this church, in front of the ones that loved you first, in front of the ones that loved you best and loved you the longest. Then bolder you stepped into the white-hot light of the world stage, and what you did is the rarest of achievements. You set the bar so high that professional singers, your own colleagues, they don’t want to sing that little country song. What would be the point?

Now, the only ones who sings your songs are young girls like you, who are dreaming of being you some day. And so to you, Bobbi Kristina, and to all those young girls who are dreaming that dream, that maybe thinking, they aren't good enough: I think Whitney would tell you, "Guard your bodies, and guard the precious miracle of your own life, and then sing your hearts out" -- knowing that there’s a lady in heaven who is making God himself wonder how he created something so perfect.

So off you go, Whitney, off you go. Escorted by an army of angels to your heavenly Father, and when you sing before Him, don’t you worry.

You’ll be good enough.

Book/CDs by Michael E. Eidenmuller, Published by

McGraw-Hill (2008)

Book/CDs by Michael E. Eidenmuller, Published by

McGraw-Hill (2008)

1

The actual title of the

referenced song is "What

Becomes of the Brokenhearted."

Page Updated: 3/21/22

U.S. Copyright Status: Text and Image (Screenshot) = Uncertain.