|

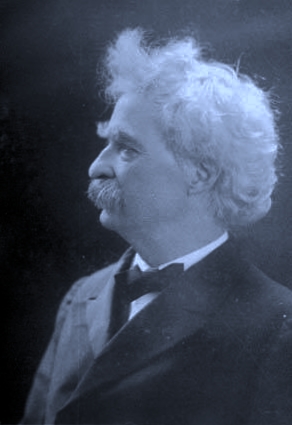

Mark

Twain

Taxes and Morals

delivered 22 January 1906, New York

click

for pdf click

for pdf

I came here

in the responsible capacity of policeman to watch Mr. Choate. This is an

occasion of grave and serious importance, and it seems necessary for me to be

present, so that if he tried to work off any statement that required correction,

reduction, refutation, or exposure, there would be a tried friend of the public

to protect the house. He has not made one statement whose veracity fails to

tally exactly with my own standard. I have never seen a person improve so. This

makes me thankful and proud of a country that can produce such men--two such

men. And all in the same country. We can't be with you always; we are passing

away, and then--well, everything will have to stop, I reckon. It is a sad

thought. But in spirit I shall still be with you. Choate, too -- if he can.

Every born American among the eighty millions, let his creed or destitution of

creed be what it may, is indisputably a Christian -- to this degree that his

moral constitution is Christian.

There are two kinds of Christian morals, one private and the other public. These

two are so distinct, so unrelated, that they are no more akin to each other than

are archangels and politicians. During three hundred and sixty-three days in

the year the American citizen is true to his Christian private morals, and keeps

undefiled the nation's character at its best and highest; then in the other two

days of the year he leaves his Christian private morals at home and carries his

Christian public morals to the tax office and the polls, and does the best he

can to damage and undo his whole year's faithful and righteous work. Without a

blush he will vote for an unclean boss if that boss is his party's Moses,

without compunction he will vote against the best man in the whole land if he is

on the other ticket. Every year in a number of cities and States he helps put

corrupt men in office, whereas if he would but throw away his Christian public

morals, and carry his Christian private morals to the polls, he could promptly

purify the public service and make the possession of office a high and honorable

distinction.

Once a year he lays aside his Christian private morals and hires a ferry-boat

and piles up his bonds in a warehouse in New Jersey for three days, and gets out

his Christian public morals and goes to the tax office and holds up his hands

and swears he wishes he may never -- never if he's got a cent in the world, so

help him. The next day the list appears in the papers--a column and a quarter

of names, in fine print, and every man in the list a billionaire and member of a

couple of churches. I know all those people. I have friendly, social, and

criminal relations with the whole lot of them. They never miss a sermon when

they are so's to be around, and they never miss swearing-off day, whether they

are so's to be around or not.

I used to be an honest man. I am crumbling. No -- I have crumbled. When they

assessed me at $75,000 a fortnight ago I went out and tried to borrow the money,

and couldn't; then when I found they were letting a whole crop of millionaires

live in New York at a third of the price they were charging me I was hurt, I was

indignant, and said: "This is the last feather. I am not going to run this town

all by myself." In that moment -- in that memorable moment -- I began to

crumble. In fifteen minutes the disintegration was complete. In fifteen

minutes I had become just a mere moral sand-pile; and I lifted up my hand along

with those seasoned and experienced deacons and swore off every rag of personal

property I've got in the world, clear down to cork leg, glass eye, and what is

left of my wig.

Those tax officers were moved; they were profoundly moved. They had long been

accustomed to seeing hardened old grafters act like that, and they could endure

the spectacle; but they were expecting better things of me, a chartered,

professional moralist, and they were saddened.

I fell visibly in their respect and esteem, and I should have fallen in my own,

except that I had already struck bottom, and there wasn't any place to fall to.

At Tuskegee they will jump to misleading conclusions from insufficient evidence,

along with Doctor Parkhurst, and they will deceive the student with the

superstition that no gentleman ever swears.

Look at those good millionaires; aren't they gentlemen? Well, they swear. Only

once in a year, maybe, but there's enough bulk to it to make up for the lost

time. And do they lose anything by it? No, they don't; they save enough in

three minutes to support the family seven years. When they swear, do we

shudder? No -- unless they say "damn!" Then we do. It shrivels us all up. Yet

we ought not to feel so about it, because we all swear -- everybody. Including

the ladies. Including Doctor Parkhurst, that strong and brave and excellent

citizen, but superficially educated.

For it is

not the word that is the sin, it is the spirit back of the word. When an

irritated lady says "oh!" the spirit back of it is "damn!" and that is the way

it is going to be recorded against her. It always makes me so sorry when I

hear a lady swear like that. But if she says "damn," and says it in an amiable,

nice way, it isn't going to be recorded at all.

The idea that no gentleman ever swears is all wrong; he can swear and still be a

gentleman if he does it in a nice and, benevolent and affectionate way. The

historian, John Fiske, whom I knew well and loved, was a spotless and most noble

and upright Christian gentleman, and yet he swore once. Not exactly that,

maybe; still, he -- but I will tell you about it.

One day, when he was deeply immersed in his work, his wife came in, much

moved and profoundly distressed, and said: "I am sorry to disturb you, John, but I must, for this is a serious matter, and needs to be attended to at once."

Then, lamenting, she brought a grave accusation against their little son. She

said: "He has been saying his Aunt Mary is a fool and his Aunt Martha is a

damned fool." Mr. Fiske reflected upon the matter a minute, then said: "Oh,

well, it's about the distinction I should make between them myself."

Mr. Washington, I beg you to convey these teachings to your great and prosperous

and most beneficent educational institution, and add them to the prodigal mental

and moral riches wherewith you equip your fortunate protégés for the struggle of

life.

Book/CDs by Michael E. Eidenmuller, Published by

McGraw-Hill (2008)

Book/CDs by Michael E. Eidenmuller, Published by

McGraw-Hill (2008)

Page Updated: 1/3/21

U.S. Copyright Status:

Text and Image

= Public Domain. |

|