|

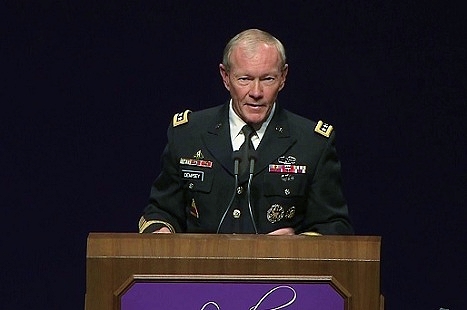

General Martin Dempsey Landon Lecture delivered 1 October 2012, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS

[AUTHENTICITY CERTIFIED: Text version below transcribed directly from audio] Thanks. Thanks very much. I am indeed delighted, honored to be here to be part of the Landon Lecture series. My wife joins me. Weíre in the midst of travel across the country. I have been trying to get here for some time actually and -- and this year we finally were able to accomplish the task. I come here just by coincidence on the day that I begin my second year as the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs. I became the Chairman one year ago today and Iím honored to fill that position at -- at this time in our nationís history, and to represent more than two million men and women in uniform, and probably twice that when you count their families. And some of those great Americans are here today and let's ask you all to stand up one more time. If youíre here in uniform stand up so the rest of us can give you a round of applause. Thanks. For those of you currently serving, duty first! Letís try that again. For those of you currently serving, duty first! There you go. I was with the Big Red One in Afghanistan last month. For those of you that are serving elsewhere, thanks for that as well. And for, I mean what youíve got framed here in this audience today is probably the senior, I was going to say oldest but I didnít like the way that was going to sound, of serving active duty officers. Iím not actually -- thereís a handful but only a handful that are more -- that are older than me but 38 years of service and Iím guessing weíve got a couple of freshmen cadets here. My promise to you is we will leave something for you to do. So, President Schultz, Jackie Hartman, Ed Seaton, staff and faculty thanks for inviting me here and thanks for what you do. I, the -- the other reason I'm glad to be here on the one year anniversary -- anniversary is that this is. I'm going to talk a little bit about the relationship of the country to its men and women in uniform. And I canít think of anything where that relationship is so powerful than right here in Manhattan, Kansas between and including the relationship between Kansas State University and the United States Army at Fort Riley, Kansas. Whether itís health of the force connections, whether itís unmanned aerial systems, whether itís education in general I really -- I really appreciate what this community and this university do for those who serve. Iím mindful of the legacy of Alf Landon by the way. As you know, among those 160 speakers who have been here with you and part of the series, thereís been seven presidents, several of my predecessors. In 1966, Alf Landon presented the first of those lectures or what would become those lectures and it was titled, "New Challenges of International Relations." Well, I would venture to say that we too serve in an era in our history where we have our fair share of new challenges in international relations. Iíll mention a few of them, not by way of being able to go into any detail about them. I could certainly address some of them in the Q and A session, but by way of showing you how these security challenges will bridge to the conversation I want to have with you about Americaís relationship with men and women in uniform. I describe one of these new international relationship challenges as a security paradox: We live in an era where we're at an evolutionary low in violence. I mean, there are people who are studying this at the -- at colleges and universities around the country. And they've concluded that we are literally at an evolutionary low in violence. State on state conflict is far less likely than it has been in the past. The problem is that other kinds of conflict, other kinds of violence are exponentially more likely as technology spreads, as the information age allows organizations and individuals, middle-weight nations if you will, to have capabilities that heretofore were the purview of major nation states. So itís a paradox in some way. The paradox being nation on nation, state on state, large conflict is less likely, not completely unlikely but less likely. But the chance of violence and those using violence for ideological and other purposes is exponentially greater: - The Arab Spring and what it will bring. The Arab Spring, as many of you have seen and probably are studying, will introduce a period of instability, is introducing a period of instability. I think that in the long run it has a very good chance of producing stability, but getting from here to there will be a challenge for not only for the United States but the region; and I would venture to say, the globe. - Iran's nuclear ambitions -- which will have to be considered in any strategy that both we and our partners in the Middle East take upon ourselves in the future. - Shifting trends, global trends really that are pulling our attention into the Pacific, economic, demographic, and military trends. And as you know our new defense strategy seeks to address those shifting global trends. - Cyber security. Cyber is the new domain, if you will: land domain, air domain, maritime domain, cyber domain. And we -- we have both incredible opportunities in cyber and we also have some significant vulnerabilities in cyber. - And a new fiscal environment. If anybody in the room thinks that my defense budget is going to go up in the next several years, please show me your hands, Iíd like to know what bar and grill you happen to frequent. I know that Aggieville is probably just about to open and Iíd send you back if I see your hand. Or maybe youíve been having too many of those maple bacon donuts that Iíve heard so much about. Look, we are living in a new fiscal environment and the -- and we those of us who serve and the department in which I serve will have to be part of solving, helping the nation solve it. And we're -- weíre hard at that and I'd be happy to talk to you about that if youíre interested. I -- I'm a fan of besides the poetry, I like to -- to dabble in a lot of different academic areas, mostly to keep my mind sharp and make sure that weíre not missing some way to articulate the challenges in front of us, and try to seek some of those solutions.

I read recently about Danish physicist

Per Bak and his

sand pile theory. Sand pile theory,

now this guy mustnít had much to do. I hope nobody is around here

doing it exactly this way, but he -- he built sand piles a grain at

a time until they collapsed. And he did this over a period of time

to try to determine if there was a way to predict when the sand pile

would collapse. And what he concluded is that what happens internal

to the sand pile is more important than what happens to it

externally, and he described that as unmappable dynamism. I think we

live in a period where weíre going to prove to ourselves that Per

Bak had it about right. Very uncertain times. You know, relationships are always a little challenging. I was, inÖ the introduction you heard that I served during operation Desert Storm in 1991. And I remember, that was the days before texting and Skypeing and Facebooking and FaceTiming and, you know, words that exist today that didnít exist, to tell you the truth, in 1991. We sent -- We sent letters back and forth to each other. And they would pass, and you know, youíd be answering questions from two letters ago and it just, it really was pretty challenging, actually. We -- We did it, but it was challenging, and I remember this one particular letter where I got, that I got from Deanie, and in it, it said, you know, Iím so miserable without you. Itís almost as though youíre actually right here with me. And I thought -- I thought to myself, boy I hope she got that sentence structure wrong, because otherwise Iím in big trouble when I come back -- come back home. But relationships are challenging. You know, youíve seen it inside your own families. Externally we have relationships around the world. But Iím suggesting to you that the relationship of -- of America and its men and women in uniform is good, could be better, could be a little deeper. And we canít take it for granted and so I want to talk about it. You know, we are, I -- I grew up in Bayonne, New Jersey, 1952, just after that group of -- of men, mostly in those days, had come back from World War II. And so I saw how their image, the image of the veteran of World War II was shaped not just by them, but by the society into which they were absorbed. I saw the same thing after Korea somewhat. I saw the same thing after Vietnam. I saw the same thing after Desert Storm. And what Iím suggesting to you is we ought to be thinking about now, what is the image, what is the veteran that you, the American people, many of you are veterans or will be veterans. And itís got to be a two-way street in answering that question. The veterans themselves canít answer it, nor can you answer it by yourselves. And we need to get after that. Now, some of you might know that some of the older folks in the audience, who will not admit that, but some of you might know that in this month 35 years ago, October of 1977, my favorite rock band, back to the music connection, my favorite rock band, The Who, recorded what I think is potentially one of the best rock songs of all times, called ďWho Are You.Ē If you remember the story, and some of you may, Peter Townshend, the lead guitarist and vocalist, was going through this inner struggle about who he was because he says, in one of the lyrics, ďI must have lost my direction because I ended up a superstar.Ē And he ended up having some significant problems in his life that he was trying to capture in that song, ďWho Are You.Ē More of you will know the song, because itís also the theme song of crime scene investigators, the ďCSIĒ series, thatís probably where you really know it. But listen to the lyrics sometime. And I would suggest to you that you might ask who are you? You really ought to know because, as I said, you will define, those of you in uniform and those of you not in uniform, you will define todayís veterans as previous generations have defined veterans in their time. Now, at one level, weíre who weíve always been, Americaís sons and daughters from all across the country from all walks of life from myriad backgrounds. As I mentioned, over 2 million active Guard and Reserve, proud to wear the cloth of the nation, proud to represent it and to go wherever and do whatever we need to do to serve in peace and in war. Thatís enduring. At another level, there are some things that are different about our service now, things that you really ought to know about. Weíre an all-volunteer force. It rolls off the tongue, but what does it really mean? Weíre an all-volunteer force. Some of you may know that only one in four of Americaís young men and women can pass the entrance requirements to even serve in the military. Thatís got to mean something to the nation. Weíre mostly married now. That wasnít the case when I came into service in 1974. As of just a few months ago, we now are serving in the longest conflict in our nationís history. Weíve asked a significant contribution, probably the most significant contribution over time of our reserve component than we have in our history. Add all those things together and add to it that most of us now have served repetitive tours in combat, that is to say a year in and a year out for the active component, a year in and three years or so out for the Reserve component. Thereís also some things you ought to know about conflict today that are different. For one thing, itís asymmetric. It, there is this constant and thereís always been some asymmetry in warfare, but itís far more prevalent today that our adversaries will seek and find ways to offset our advantages and leverage some of theirs, asymmetric. So you have to constantly be adapting to whatís going on around you. Second thing is itís persistent. Thereís no letís go to the rear and take a break. When youíre in it, youíre in it and itís part of your life. Itís part of your daily life. Itís a moment-to-moment. Think about a young man or woman on patrol in parts of Afghanistan today where the IED, the pressure plate underground buried mine is a prevalent form of warfare. And the incredible courage on the one hand, but the incredible anxiety on the other, of not knowing whether your next step could potentially be your last. Itís persistent. Itís nonlinear. Itís everywhere. There is no place to go to find sanctuary. Itís decentralized. And what I mean by that is a young captain might have more responsibility, more authority, more capability at his disposal than a colonel did in previous conflicts. Or a lieutenant colonel battalion commander will have more capability, authority and responsibility than I had as a division commander in Baghdad in 2003. And hereís an important one, we take our families to war with us. Now, of course I donít mean that literally, but I mean it absolutely, figuratively, and I mean it emotionally. Itís absolutely not uncommon, or to -- to avoid the double negative, it is absolutely common that a young man or woman will be Skypeing or texting or emailing or FaceTiming and say, ďHey look, I got to go now. I got to go out on patrol. Iíll call you when I get back.Ē Happens every day all the time everywhere and that puts a different kind of -- of emotional pressure on both sides, by the way. Now look, thatís just the reality of the conflict in which we find ourselves. But when you add it all together, I think itís important for you to know who we are. The question is who are you in all of that? So what does that require of those who serve, many of whom are sitting in this audience today? Well, courage, but thatís not a new requirement really is it? I do want to tell you about one particular airman I met actually, Air National Guard Master Sergeant Roger Sparks, Alaska Air Guard. And heís a parajumper. Parajumpers are these fellows and gals who lower themselves out of usually Black Hawk helicopters on a cable, on a wire rope to rescue someone. Coast Guard does it at sea, this guy was happening to do it in Afghanistan on the side of the Hindu Kush with the 10th Mountain Division. And on a particular day, on a particularly -- on a particularly difficult piece of terrain, he pulled 12 soldiers off the side of a cliff fundamentally, under fire. Four of them died in his arms. He -- He recovered all 12. Four of them died in his arms. And -- And each time he lowered himself he was attacked by machine gun fire from the enemy. And in fact, the wire rope on which he was suspended was struck twice and held up under the fire. Thatís -- Thatís courage. Thereís something else there too. Itís some kind of sense of belonging or some -- some sense of loyalty to comrades. Resilience. Again, not necessarily a new characteristic of those who serve, but I would suggest to you that itís resilience thatís being tested in ways that it hasnít been in a very long time. I met, not so long ago, when I was asked to be the head of delegation for the Paralympics. I was honored to represent the United States as the head of delegation to the Paralympics. And I met Navy Lieutenant Brad Snyder. He was blinded one year ago in Afghanistan. This year he won two gold medals and a silver. Now thatís resilience. If youíre looking in the dictionary for resilience, look there. And that -- that by the way applies not only to our men and women who serve, but to the families that support them. Thatís who we are. Who are you? Resolve. Now, this is a peacetime example but itís worth noting. I have a young sergeant first class working in my outer office by the name of Samantha Johnson. Samantha Johnsonís about five foot two, as mean as a snake, strong as an ox. Hereís what Samanthaís done. She deployed to Iraq as a driver for an EOD team, explosive ordinance demolitions, that is to say a route clearance team, and she was a driver. She came back and almost immediately in her particular specialty, they needed somebody in Afghanistan because the guy who was doing the job had gotten, had come down with cancer. So she deployed almost immediately, back to back. She is a drill sergeant, was a drill sergeant. She is working on her second masterís. And she has a part-time job as a security guard so she can pay off her mortgage. Iíd -- Iíd call that resolve. That young lady knows what she wants. And then adaptable. This one might be the one where I would suggest to you that todayís form of conflict requires a special emphasis on a particular attribute and that attribute is adaptability. Weíve got to be faster on our feet. Weíve got to be inquisitive. You know, Einstein once said, probably being a little falsely humble, but he said, ďYou know, Iím not really the smartest guy, but Iím passionately inquisitive.Ē And I think thatís a quality that we need to encourage, not just in the men and women in uniform, by the way, but really in our nation, to be passionately inquisitive; to keep up, in our case, with -- with what changes on the battlefield, but in the case of the population in general, what takes place in everyday -- in everyday technology changes, in everyday relationship issues, passionate curiosity. So what weíve done over the past 10 years, I would describe to you, is weíve overcome physical fear. Physical fear is always part of the battlefield. Weíve overcome physical fear by developing new instincts. You know that when that big tsunami hit in Thailand about six or seven years ago now, you probably read the story that the animals ran. When the animals sensed that the sea was receding, the animals headed inland and up, and up to higher elevations. The people there on vacation said wow isnít this cool? Letís go out and see whatís at the bottom of this, and what happened? Back in came the tsunami and killed far too many. Weíve got to have new instincts for the world in which we find ourselves. And weíve got to maintain, importantly, that sense of belonging and that sense of purpose that has defined us throughout our history as military but also has defined us throughout our history as Americans. So thatís kind of maybe the obvious. Let me state a little bit of the less obvious. Many times even the toughest of veterans that are coming home will tell you that in some ways coming home is tougher than being in the combat zone. Why would that be? Well, remember I mentioned repetitive tours. Itís the emotional fear of constantly having to reintegrate with your family as they grow while youíre not there. Thatís a reality. Secondly, there is in combat a very singular focus. You know exactly what you have to do. Your purpose is defined, your mission is clear. The enemy will always confuse you at times. Thereíll be fog and friction, but you have a sense of clarity thatís uncanny in combat. And then you return and hereís the words of one particular veteran, to the million tiny anxieties of life outside the combat zone. He described it, this particular writer, as going from war at, where war is at max volume and in the foreground, and coming back to where war is at much lower volume and in the background. Max value, max volume and in the foreground; low volume and in the background. And itís difficult for our veterans to reconcile that. And finally and importantly, theyíre coming back into the uncertainty of a difficult economic situation, a difficult economic environment and the uncertainty of employment. Now, look, Iím only telling you that to support my thesis here, which is weíre -- weíre at that point now, after ten years of prolonged conflict and what appears to be continued challenges of that nature going into the future because of my security paradox. The question is, then, what is that image? What -- What image is in your mind of the veteran? And is there some -- something you should be doing to help shape it? The veterans of the past decade are you, or at least thatís what they want to be. Each in their own way has served heroically. Each in their own way has served heroically, but theyíre not all heroes. Many have experienced real horrors of war, but theyíre not all victims. All have served America and want to continue to serve her as they transition into your civilian communities. On that basis alone, on the expectation that itís in our shared interest, you and I, in and out of uniform, that we allow this generation of veterans to contribute, to bring the strengths that they bring, to bring the passionate curiosity that Iíve described, notwithstanding the pressures that theyíve felt. To the extent that we should agree that we all want a stronger America, then we ought to find a way to make sure that these veterans are part of it. And we ought to work together with them, not for them, with them. Ultimately, who are you is a question that must be answered both by these veterans and the nation that sent them to war. Iíll end with a favorite quotation of mine, ďBad times, hard times, this is what people keep saying. But let us live well, and the times shall be good. We are the times. Such as we are, such are the times.Ē St. Augustine, fourth century. Thank you very much. Moderator: Wonderful comments and your thought-provoking theme. I know that I confused many of you when I came up here. I look so much like Kirk Schulz. My name is April Mason, and I serve as the Provost here at Kansas State. I thought I might clear that up. The general will take questions now. We have microphones on either side of the auditorium. Iíd ask you to make your way to those and wait for me to recognize you to pose the question. And we greatly appreciate you being willing to take questions, General.

Please. Dempsey: What I, yeah, what I really said, what the general meant to say was -- was that I think the Defense Department, as well as the rest of theÖ entire governmental enterprise, will have to find ways to help us address our common economic challenges, and that I expect, therefore, that Iíll have a smaller budget rather than a big one. I, you know, theÖ cut question assumes that the reductions will be taken on the back of force structure or end strength. And thatís not necessarily, weíve already got some end strength reductions planned. I donít know that we know enough about whether sequestration will be detriggered or not to know whether we have to look at other force structure reductions. That -- That remains to be seen. That said, the real question is what needs to change based on the lessons of the last ten years of war? And I would venture to say that among the changes are that, I -- I mentioned decentralization. Conflict is somewhat decentralized and networked. So the military that I came into started thinking about conflict as large organizations that would disaggregate as necessary. Iím suggesting that potentially we -- we will need to begin to think about building small organizations that can aggregate as necessary. And thatíll bring us to some conclusions about changes to force structure. Q: Sir, I have a question. What is, whatís your advice for the next military leaders of tomorrow? Dempsey: Cheer me on, because if I leave you a mess, youíre not going to be very happy about it. No, Iím kidding. Iíll give you something. My advice -- My advice is to, you know, youíve already, what, are you in the service? Are you coming into the service? Where are you? Where, who are you?

Go ahead. Dempsey: Great. Well, look, I, you know, I think youíve made a decision. I meanÖ, I could answer a question with a question about why you chose to do what youíre about to do. But I think I know most of the answer, and, because youíre looking for that sense of purpose, that sense of belonging that -- that the military provides young men and women. I -- I would suggest to you that at -- at whatever rank you find yourself, you know, youíre going to start out as a second lieutenant. Be the best second lieutenant you can be. Bloom where, you know, bloom where youíre planted. Iíll take care of Washington, D.C., you take care of Fort Riley, Kansas, and I think weíll be fine. Q: Good afternoon, sir. I am Abdulraheem Alkhiary, dual major here at, in political science and finance. I would like first of all to thank you on behalf of the Saudi Club for serving in the Gulf War. Second of all, there is many things going on in the old world. You have Afghanistan and you have the Arab Spring, et cetera. Two questions comes out of that. The situations that are happening right now in Afghanistan, where you have many U.S. soldiers getting shot by their Afghani colleagues, the question comes, why, what encourages the Afghanis to shoot their colleagues? Whatís the cause of that? I want to get your opinion from that. And would the U.S. change their relationship, the second question, would the U.S. change its relationship somehow with Libya, Egypt and Tunisia because of the protests thatís been happening around the embassies and the murder of the U.S. ambassador in Libya? Thank you. Dempsey: Yeah, IídÖ have to stay here for two or three days to do justice to those questions, but -- but I will give you, Iíll -- Iíll react to both very briefly. First of all, Afwan, It was my great honor to serve in the Ė- in the 1991, as it is today. Secondly, on the, we call them insider attacks. The one thing weíve learned over the past ten years I think is that weíve reinforced, you know, for every really complex problem, thereís a simple solution and itís almost always wrong. So this is a really complex issue, one that demands that we understand it, and that as we understand it, we do that collaboratively with our Afghan partners. Itís, it is a -Ė it is, as Iíve said before, a very serious threat, and one that we are seized with addressing. WeíreÖ likely not to eliminate it entirely, but I think we can do a heck of a lot better at getting it under control, especially if we get the cooperation of our Afghan partners. And I met just last week with the new minister of defense ofÖ Afghanistan, the new minister of interior, a couple of the corps commanders. And Iím, I left there convinced that they are as concerned about this as we are. But weíve got a lot of work to do. And it is -- it is a tactic being employed by the Taliban and those who are ideologically opposed to the kind of Afghanistan we see in the best interests, both of them and us, in the future. The Arab Spring is kind of the same, itís, meaning itís that complex geopolitical issue with -- with ideological and religious undertones. It is, it has, you know, dozens of stakeholders who are seeking to influence the outcome. You asked will we abandon it just because of, I shouldnít say just because. Will we abandon it because of some of the recent demonstrations and riots and even the loss of our -Ė of our Ambassador? You know, Ambassador Chris Stevens would be the first one to say, the first one to say under no circumstances should we abandon that part of the world simply because of the acts of a few terrorists, fundamentally. And so I donít think we will. But weíve got, you know, this is a very complex time, and we want to make sure that we employ all of the instrumentst we partner with those who have common interests in the region to try to find a way to -- to settle those issues for the long term. Q: General, thank you, excuse me. General, thank you for coming. What, in your view, is the strategic value of the bases outside the United States? We have bases in Japan, Germany, South Korea. In light of the rapid-response abilities of the current U.S. military, carrier battle groups, Marines, airborne, et cetera? And are those bases outside the U.S., are they worth the cost and political struggle? Thank you. Dempsey: Yeah, Iím -- Iím actually one who -- who believes very strongly in maintaining a forward presence for a couple of reasons that, some which are obvious. The access issue is -- is clearly one of them, but also what it does for us. I think, meaning the development of our leaders, I think there is a significant advantage to allowing our leaders to grow up inside of different cultures, different languages, different customs and traditions, so we get to know each other before we potentially have to go fight with each other, because itís, Iím telling you, what Iíve learned over the -- over the, even just this first year as Chairman is that at the end of the day, you know, process, itís important to understand process. Itís vital to build relationships. And I think that our presence allows us to build a relationship of trust that just our deployments wouldnít allow. I mean, my wife and I have lived in Germany for 12 years, we lived together in Saudi Arabia for two years and Iíve been in Iraq for three. And if you add up my time in Afghanistan, itís probably one-plus. And so obviously youíre talking to someone who believes we really -- we really have to be engaged in the world to help influence it, not do it from 6,000 -- 6,000 miles away. Q: Sir, Iím a cadet in the Air Force ROTC here. Iím about to graduate this May, and I was wondering what the Air Force or the military in general, in the Pacific, what you see being the focus of our mission, say, five, ten years where Iíll be serving? Dempsey: Well, I, you know, as you know, the new defense strategy talked about rebalancing to the Pacific. Weíve been very careful not to describe that as a light switch, you know, one day youíre there, the next day youíre not. We never left, really. We just shifted our balance to the Mideast because thatís where the security, the greatest security issues of the last ten years have -- have happened to reside. I think itís a fair, as again, as you watch demographic trends, economic trends and military trends, you will see them trending toward the Pacific. And we want to be, you know, Wayne, let me give you a Wayne Gretzky. Iím all over the map today with my eclectic quotations here, from St. Augustine to Wayne Gretzky. I donít know whatís going on. Wayne Gretzky, about your size, probably the best hockey player in history, we could debate that, I suppose. But somebody said to him once, you know, youíre not really a physically imposing guy. How do you, how come you were such a great hockey player? And he said, ďI skate to where the puck is going to be, not to where itís been.Ē Thatís what weíre trying to do. Q: General, obviously you talked a lot about reintegrating soldiers coming back from deployment. How do you think higher education at colleges, universities such as K State, play a role in that? What steps do you think colleges have allowed soldiers to maybe go back and earn a degree and -- and have a greater access to the job market and how -- how that helps them reintegrate? And what steps do you think need to be taken by higherÖ education? Dempsey: Yeah, one of the, I think that first of all, I think the partnership with higher education isÖ terrific. I mean, I -- I couldnít be more pleased with every place I go, higher education is -- is seeking to -- to increase the degree to which we partner with each other. I think weíve got to do a little, I think we both have some work to do. I think weíve got to do a little better job of preparing our veterans to -- to move into that environment. Remember what I said about, you know, a veteran coming out of Iraq and Afghanistan goes from, you know, life at Mach 4 to something far slower and -- and somewhat more muted, and I -- and I think that, when I look at how we prepare veterans to move into -- into this civilian society and into education in particular, thereís some work we can do. We -- We just did, with the Veterans Administration, revise our transition programs. And I think theyíll be -- theyíll be better, and weíll continue to adapt them as necessary, at preparing veterans to enter academia. On the part of -- of academia, I think you have to understand that theyíre not high school kids coming out of senior year and matriculating into a normal academic experience. They, first of all, they come with -- they come with some incredible strengths, they come with some vulnerabilities because of all the things I just mentioned. And there are some organizations, veteran support organizations, that are kind of growing up around the country that letís call it mentor these young men and women that come into higher education, because our Ė- because our drop-out rateís too high right now. And so I think we need to, we need a little help, and we need do to some things ourselves. Q: Hello, sir. My name is Kristy Robinson. Iím the widow of Sergeant Jessie Earl Robinson, and Iím also a student at K State. Iím getting a dual major in mathematics and secondary education. And my concern today is about that there are many of our service members and veterans who return home and suffer PTSD, and when this is left untreated, it often results in a suicide, as was the case with my husband. And I was wondering, what can the nation or our communities and the military do to better treat and help our soldiers and veterans and help take care of their families, you know, as the soldiers are dealing with the post-traumatic stress, anxiety and reintegration issues? Dempsey: Yeah. Well, first of all, Iím deeply sorry for your loss, and I thank you profoundly for stepping forward to tell us your story. How about we all give her a round of applause? The effort in PTSD is -- is one of those issues where we have to be on a campaign of learning. So if we were to have this conversation ten years ago, we were trying to increase the, we still are trying to increase the protection at the point of impact. You know, weíre putting mechanical devices on helmets that sense that, you know, pressure from blast effects. Thatís part of it. Weíre also partnering with, by the way, with the National Football League and other sports experts to try to understand how to reduce the impact. But then thereís some medicine and chemistry. A good friend of mine, Pete Chiarelli, who I was supposed to meet for dinner tomorrow, is on a campaign, you probably know Pete Chiarelli, at least you know him by name, he was the Vice Chairman, Vice Chief of Staff of the Army, and probably our most, our -Ė our most active, passionate advocate for the study of PTSD and how to map it, how to understand it, you know, because it isÖ how to reduce the stigma, all the things that Iím sure you could speak to me about far more eloquently than I can speak to you. In the time available, what I will tell you is we are absolutely seized with -- with PTSD, moderate traumatic brain injury and suicide, as well as some other things, and -- and the effects of prolonged, repeated conflict. Suicide in particular, though, is not uniquely a military challenge, as you well know. But I promise you, we are not, weíre not complacent about this. We are seized with it. And I really do appreciate you giving me the opportunity toÖ assure you of that. Thank you. Q: General, thank you for being here. Going along with what she said, to the men in service, to the servicemen and women that are returning from deployment to civilian population, what do you think we as a society could help them cope better into emerging into civilian population again? Dempsey: No, thatís a great question. Itís the conversation Iím hoping to start. I mean, the conversation has started. Maybe what Iím trying to do is turn the volume up a little bit, because, you know, weíre, Iraq is -- is no longer our fight. The Iraqi people, the Iraqi security forces have taken that on for themselves. Afghanistan will soon do the same. And weíll have more veterans back in this country transitioning out. The budget reductions we talk about will likely, no, not likely, it will create more veterans. And so I want to have that conversation now before this all begins to happen in big numbers. And I donít know the answer. IÖ and in fact, Iíve studied it. Iíve read, I mean, Iím a pretty voracious reader. Iím trying to read everything that veterans are saying. I canít get it all. Thereís even some novelists that are, meaning literary authors who are taking this up. Thereís a book I just read called ďBilly Lynnís Long Halftime WalkĒ thatís kind of a, Iím not, by the way, this is not a promotion for the book, but itís actually, itís kind of the, ďCatchĒ if you remember the book ďCatch-22Ē and Vietnam, this is kind of ďCatch-22Ē for the past ten years. Itís pretty interesting. I donít agree with all of it, but I want to understand it, and I want you to be part of the conversation. And, you know, it, this is kind of one of those places where we all say thanks to them, but how much, you know, how -- how often do we take the time to ask them to share their experiences, or how -- how often are you willing to share your experiences? I think we have to have a conversation, because look, this isnít about forming an image of the veteran for us. This is about forming an image of the veteran for America, because every generation does that. And itís now time for us to do that. And I really want the image to be positive. And so, because it should be positive. So I need your help. I canít answer the question for you, but I need your help in answering it.

Moderator: Weíll be able to

take one last question. Dempsey: Well, it, since itís the 21st century, one of the premises I have is that our ability to connect should be a heck of a lot more, it should be a lot more possible for us to make the kind of connections youíre talking about in this century than it was in the last century. Thatís -- thatís a given. And so leveraging, I think, technology to share some common appreciation and understanding of -- of where these young men and women are, what they, I mean, Iím trying to transition the -- the personnel system of our military, this is kind of my challenge, which is kind of industrial age, you know, and the -- the ability of the young men or women to kind of have a hand in crafting their career differently than we have had in the past is possible today given technology. So Iím trying to, that by the way, this is hard -Ė this is hard government work. But on the other side, I think thereís some, there are some opportunities. I think public-private partnerships tend to work better than to expect me or the government to do everything top-down. The -- The most successful programs for helping veterans, for -- for even for things like our acquisition strategies are generally public-private partnerships and -- and almost always grow from the bottom up. I think, I just have this sense that if I -- if I challenge you and challenge America to help me figure this out, I think the tools are there to figure it out, but I canít do it by myself.

Moderator:

When was it that you went to a talk and the theme was from The Who

and you had quotes from St. Augustine and Wayne Gretzky? I think we

have heard a very insightful view into the actions of our military,

and you have answered so many wonderful questions. I thank the

audience for those.

Audio, Image (Screenshot) Source:

DVIDShub.net

Research Note:

Transcription by

Diane Wiegand

Audio Note: AR-XE = American Rhetoric Extreme Enhancement Page Updated: 1/5/24 U.S Copyright Status: Text, Audio, Image = Public domain. |

|

|

© Copyright 2001-Present. |