|

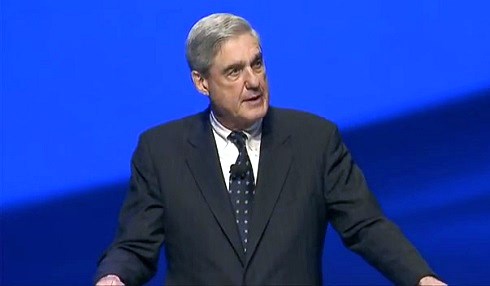

Robert Mueller RSA Cyber Security Conference Address delivered 01 March 2012, San Francisco, CA

Well, good afternoon, everyone. Good afternoon. It's -- I must say I'm honored to be here and gratified to be back in glorious San Francisco. About four hours ago, when it was raining hard, I eliminated the "glorious," but the day has changed so, it again is glorious San Francisco. Now, a few weeks ago, there was a story in The New York Times about a woman who was taking a break from work. She was watching YouTube videos on her iPhone when a man walked up, pointed a gun at her, and grabbed the phone and ran. A New York City police officer responded to the call and told her not to worry, that he would find her phone. And he grabbed his own phone, opened the “Find My iPhone” app, and typed in the victim’s Apple ID. And in seconds, a phone icon popped up, showing that the subject was near 8th Avenue and 51st Street. And the officer and his partner headed that way. And as they pulled up, the officer pushed a button on his phone and they began to hear a pinging noise some 20 feet away. The officer hit "Play" one more time and they followed the pinging to its source, which turned out to be in the man’s sock. Now, the Times reporter pointed out that had the subject -- had he been tech savvy, he might have known how to disable the iCloud setting and stop the trace. And from our perspective in law enforcement, if only -- we would wish -- every case could be solved so easily -- and in less than 30 minutes. Technology has become pervasive as a target. It has also been used as a means of attack. But this story illustrates our use of technology as an investigative tool. And it also illustrates the power of innovative thinking and fast action -- the very tools we need to stop those who have hijacked cyberspace for their own ends.

Technology is moving so rapidly that from a security perspective, it is difficult to keep up. Consider the evolution of cyber crime in just the past decade. When I was the U.S. Attorney here in 2000, we worked with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to track down a Canadian teenager known as “MafiaBoy.” He was responsible for the largest denial-of-service attack at that time. He targeted eBay, Yahoo, E*Trade, Global Crossing, and CNN, just to see if he could shut them down -- and he could and did. When he was finally caught, the 15-year-old was reportedly at a sleepover at a friend’s house, eating junk food and watching "Goodfellas." He said at the time that he did not understand the consequences of his actions. That now seems like the good old days. Traditional crime -- from mortgage and health care fraud to child exploitation -- has migrated online. Terrorists use the Internet as a recruiting tool, a moneymaker, a training ground, and a virtual town square, all in one. At the same time, we confront hacktivists, organized criminal syndicates, hostile foreign nations that seek our state secrets and our trade secrets, and mercenaries willing to hack for the right price. And we have seen firsthand what happens when countries launch cyber attacks against other nations as a means of exerting power and control. Today we will discuss what we in the FBI view as the most dangerous cyber threats, what we are doing to confront these threats, and why it is imperative that we work together to protect our intellectual property, our infrastructure, and our economy. Let me begin with cyber threats to our national security. Terrorists are increasingly cyber savvy. Much like every other multi-national organization, they are using the Internet to grow their business and to connect with like-minded individuals. And they are not hiding in the shadows of cyber space. Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula has produced a full-color, English-language online magazine. They are not only sharing ideas, they are soliciting information and inviting recruits to join al Qaeda. Al Shabaab -- the al Qaeda affiliate in Somalia -- has its own Twitter account. Al Shabaab uses it to taunt its enemies -- in English -- and to encourage terrorist activity. Extremists are not merely making use of the Internet for propaganda and recruitment. They are also using cyber space to conduct operations. The individuals who planned the attempted Times Square bombing in May 2010 used public web cameras for reconnaissance. They used file-sharing sites to share sensitive operational details. They deployed remote conferencing software to communicate. They used a proxy server to avoid being tracked by an IP address. And they claimed responsibility for the attempted attack -- on YouTube. To date, terrorists have not used the Internet to launch a full-scale cyber attack. But we cannot underestimate their intent. In one hacker recruiting video, a terrorist proclaims that cyber warfare will be the warfare of the future. Terrorist use of the Internet is not our only national security concern. As we know, state-sponsored computer hacking and economic espionage pose significant challenges. Just as traditional crime has migrated online, so, too, has espionage. Hostile foreign nations seek our intellectual property and our trade secrets for military and competitive advantage. State-sponsored hackers are patient and calculating. They have the time, the money, and the resources to burrow in, and to wait. They may come and go, conducting reconnaissance and exfiltrating bits of seemingly innocuous information -- information that in the aggregate may be of high value. You may discover one breach, only to find that the real damage has been done at a much higher level. Unlike state-sponsored intruders, hackers for profit do not seek information for political power -- they seek information for sale to the highest bidder. These once-isolated hackers have joined forces to create criminal syndicates. Organized crime in cyber space offers a higher profit with a lower probability of being identified and prosecuted. Unlike traditional crime families, these hackers may never meet, but they possess specialized skills in high demand. They exploit routine vulnerabilities. They move in quickly, make their money, and disappear. No company is immune, from the Fortune 500 corporation to the neighborhood "mom and pop" business. We are also worried about trusted insiders who may be lured into selling secrets for monetary gain. Perimeter defense may not matter if the enemy is inside the gates. The end result of these developments is that we are losing data. We are losing money. We are losing ideas and we are losing innovation. And as citizens, we are increasingly vulnerable to losing our information. Together we must find a way to stop the bleeding. We in the FBI have built up a substantial expertise to address these threats, both here at home and abroad. We have cyber squads in each of our 56 field offices, with more than 1,000 specially trained agents, analysts, and forensic specialists. Given the FBI’s dual role in law enforcement and national security, we are uniquely positioned to collect the intelligence we need to take down criminal networks, prosecute those responsible, and protect our national security. But we cannot confront cyber crime on our own. Borders and boundaries pose no obstacles for hackers. But they continue to pose obstacles for global law enforcement, with conflicting laws, different priorities, and diverse criminal justice systems. With each passing day, the need for a collective approach -- for true collaboration and timely information sharing -- becomes more pressing. The FBI has 63 legal attaché offices that cover the globe. Together with our international counterparts, we are sharing information and coordinating investigations. We have special agents embedded with police departments in Romania, Estonia, Ukraine, and the Netherlands, working to identify emerging trends and key players. Here at home, the National Cyber Investigative Joint Task Force brings together 18 law enforcement, military, and intelligence agencies to stop current and predict future attacks. With our partners at DHS, CIA, NSA, and the Secret Service, we are targeting cyber threats facing our nation. The task force operates through Threat Focus Cells -- specialized groups of agents, officers, and analysts that are focused on particular threats, such as botnets. Together we are making progress. Last April, with our private sector and law enforcement partners, the FBI dismantled the Coreflood botnet. This botnet infected an estimated two million computers with malware that enabled hackers to seize control of zombie computers to steal personal and financial information. With court approval, the FBI seized domain names and re-routed the botnet to FBI-controlled servers. The servers directed the zombie computers to stop the Coreflood software, preventing potential harm to hundreds of thousands of users. In another case, just a few months ago, we worked with NASA’s Inspector General and our partners in Estonia, Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands to shut down a criminal network operated by an Estonian company by the name of Rove Digital. The investigation, called Operation Ghost Click, targeted a ring of criminals who manipulated Internet "click" advertising. They re-directed users to their own advertisements and generated more than $14 million in illegal fees. This "click" scheme impacted more than 100 countries and infected four million computers, half-a-million of which were here in the United States. We seized and disabled computers, froze the defendants’ bank accounts, and replaced rogue servers with legitimate ones to minimize service disruptions. With our Estonian partners, we arrested and charged six Estonian nationals for their participation in the scheme. And again, we must continue to push forward together. Terrorism remains the FBI’s top priority. But in the not too distant future, we anticipate that the cyber threat will pose the number one threat to our country. We need to take lessons learned from fighting terrorism and apply them to cyber crime. We will ensure that all of our special agents have the fundamental skills to operate in this cyber environment. Those agents specializing in cyber matters will have the greatest possible skill set. We are creating a structure whereby a cyber agent in San Francisco can work in a virtual environment with an agent in Texas, an analyst in Virginia, and a forensic specialist in New York to solve a computer intrusion that emanated from Eastern Europe. At the same time, we must rely on the traditional capabilities of the Bureau: sources and wires. We must cultivate the sources necessary to infiltrate criminal online networks, to collect the intelligence to prevent the next attack, and to topple the network from the inside. We must ensure that our ability to intercept communications -- pursuant to court order -- is not eroded by advances in technology. These include wireless technology and peer-to-peer networks, as well as social media. We will also continue to enhance our collective ability to fight cyber crime. Following the September 11th terrorist attacks, we increased the number of Joint Terrorism Task Forces. Today, we have more than 100 such task forces -- with agents, state and local law enforcement officers, and military personnel -- working together to prevent terrorism. We are developing a similar model to fight cyber crime -- to bolster our capabilities and to build those of state and local law enforcement as well. Along these same lines, 12 years ago we joined forces to address both the growing volume and complexity of digital evidence. Together with our state and local partners, we created the first Regional Computer Forensics Laboratory in San Diego. Today, we have 16 such labs across the country, where we collaborate on cases ranging from child exploitation to public corruption. Together we are using technology to identify and prosecute criminals and terrorists. Working with our partners at DHS and the National Cyber-Forensics Training Alliance, we are using intelligence to create an operational picture of the cyber threat -- to identify patterns and players, to link cases and criminals. Real-time information-sharing is essential. Much information can and should be shared with the private sector. And in turn, those of you in the private sector must have the means and the motivation to work with us. We in the Bureau are pushing for legislation to provide for national data breach reporting. This would require companies to report significant cyber breaches to law enforcement and to consumers. Forty-seven states already require the reporting of data breaches, but they do so in different ways and to different degrees. We must continue to break down walls and to share information, in the same way we did in the wake of the September 11th attacks. This includes the walls that sometimes exist between law enforcement and the private sector. You here today are often the first to see new threats coming down the road. You know what data is critically important, and what could be at risk. And while you are fierce competitors in the marketplace, you routinely collaborate behind the scenes. For example, Microsoft, Google, Facebook, and Bank of America, along with several other companies, have joined forces to design a system to authenticate legitimate e-mails and weed out fake messages. Such collaboration is commonplace now. But 12 years ago in the "Mafiaboy" case, several of the affected companies shared their experiences and worked together -- for the first time -- to present a united front against that denial of service attack. Public-private partnerships are equally important. Through the FBI’s InfraGard program, individuals in law enforcement, government, the private sector, and academia meet to talk about how to protect our critical infrastructure. Over the past 15 years, InfraGard has grown from a single chapter in the Cleveland FBI Field Office to more than 85 chapters across the country, with more than 47,000 members. Recently, after attending a local InfraGard meeting, one member recognized a phishing scam and notified the FBI. We identified 100 U.S. banks that had been victimized by unauthorized ATM withdrawals in Romania. Eighteen Romanian citizens were charged and eight individuals were extradited to the United States. Three have pled guilty, with one sentenced to more than four years in prison. We in the FBI understand that you may be reluctant to report security breaches. You may believe that notifying the authorities will harm your competitive position. You may fear that news of a breach will erode shareholder confidence. Or you may think that the information flows just one way -- and that is to us. We do not want you to feel victimized a second time by an investigation. We will minimize the disruption to your business, and we will safeguard your privacy. Where necessary, we will seek protective orders to preserve trade secrets and business confidentiality. And we will share with you what we can, as quickly as we can, about the means and the methods of attack. But maintaining a code of silence will not serve us in the long run. For it is no longer a question of "if," but "when" and "how often." I am convinced that there are only two types of companies: those that have been hacked and those that will be. And even they are converging into one category: companies that have been hacked and will be hacked again. Given that scenario, we must limit the data that can be gleaned from any compromise. We must segregate mission-centric data from routine information. And we must incorporate layers of protection and layers of access to critical information. We may need to look at alternative architectures that are more secure...that allow critical infrastructure owners and operators to better spot threat actors and to provide information to law enforcement to track and to catch them. Attribution is critical to deter future attacks. We cannot just minimize vulnerabilities and deal with the consequences. Collectively, we can improve cyber security and lower costs -- with systems designed to catch threat actors rather than to withstand them. Several months ago, I read William Powers’ book, "Hamlet’s BlackBerry," about the impact of technology on civilization. In one chapter, he wrote about the Roman philosopher Seneca. In the days of the Roman Empire, connectivity was on the rise -- new roads, new ways of communicating, and a new postal system to handle the influx of written documents. Postal deliveries were the high point of the day. People coming from every direction would converge at the port to meet the delivery boats arriving from Egypt. As they say, the more things change, the more they stay the same. Today we have the so-called "BlackBerry Jam," where several individuals -- heads down, shoulders slumped, all furiously typing, talking, reading, or browsing at once -- come to a head on a crowded corner. We are all guilty of this conduct. All those years ago, Seneca argued that the more connected society becomes, the greater the chance that the individual will become a slave to that connectivity. Today, one could argue that the more connected we become, the greater the risk to all of us. We cannot turn back the clock. We cannot undo the impact of technology. Nor would we want to. But we must continue to build our collective capabilities to fight the cyber threat. We must share information. We must work together to safeguard our property, our privacy, our ideas, and our innovation. We must use our connectivity to stop those who seek to do us harm. Thank you and God bless.

Original Text

Source:

FBI.gov

Page Updated: 2/19/21 U.S Copyright Status: Text = Public domain. Image (Screenshot) = Fair Use. |

|

|

© Copyright 2001-Present. |