[AUTHENTICITY CERTIFIED: Text version below transcribed directly from audio]

Members of the Academy, members of the Philosophical Society:

What you have good reason to wish to hear from me today, what circumstances have perhaps qualified me to discuss with you on the basis of experience, is how to make atomic weapons. It is true, as we have so often and so earnestly said, that in the scientific studies which we had to carry out at Los Alamos in the practical arts there developed, there was little fundamental discovery. There was no great new insight into the nature of the physical world.

We had many surprises. We learned a good many things about atomic nuclei and many more about the behavior of matter under extreme and unfamiliar conditions, and not too few of the undertakings were in their quality and their style, worthy of the best traditions of physical science.

It would not be a dull story. It is being recorded in a great handbook of 15 volumes, much of which we think will be of interest to scientists, even if they are not by profession, makers of atomic bombs. It would be a pleasure to tell you a little about it. It would be a pleasure to help you to share our pride in the adequacy and the soundness of the physical science of our common heritage that went into this weapon that proved itself last summer in the New Mexico desert.

That would not be a dull story, but it is not one that I can tell today. It would be too dangerous to tell that story. That is what the President, on behalf of the people of the United States, has told us. That is what many of us, where we forced ourselves to make the decision, might well conclude.

What has come upon us, that the insight, the knowledge, the power of physical science, that the cultivation of which, to the learning and teaching of which we are dedicated, has become too dangerous to be talked of, even in these halls. It is that question that faces us now, that goes to the root of what science is, of what its value is. It is to that question to which tentatively, partially and with a profound sense of its difficulty and my own inadequacy I must try to speak today.

It is not a familiar question to us in these late days. It is not a familiar situation. If it seems to bear analogy to that raised by other weapons, to the need for certain secrecy, let us say, in the discussion of howitzers or torpedoes, that analogy will mislead us. There are some accidents in this situation, some things that may in the large light of history seem contingent.

Atomic weapons are based on things that are in the very frontier of physics. Their development is inextricably entangled with the growth of physics, as in all probability with that of the biological sciences and many practical arts. Atomic weapons were actually made by scientists; even some of you may think by scientists normally committed to the exploration of rather recondite things.

The speed of the development, the active and essential participation of men of science in the development, have no doubt contributed greatly to our awareness of the crisis that faces us, even to our sense of responsibility for its resolution. But these are contingent things.

What is not contingent is that we have made a thing, a most terrible weapon, that has altered abruptly and profoundly the nature of the world. We have made a thing that, by all standards of the world we grew up in, is an evil thing. By so doing, by our participation in making it possible to make these things, we have raised again the question of whether science is good for man, of whether it is good to learn about the world, to try to understand it, to try to control it, to help gift to the world of men increased insight, increased power.

Because we are scientists, we must say an unalterable "yes" to these questions. It is our faith and our commitment, seldom made explicit, even more seldom challenged that knowledge is a good in itself. Knowledge and such power as must come with it.

One will perhaps think back to the early days of physical science in Western culture, when it was felt as so deep a threat to the whole Christian world. One will remember the more recent times of the last century, where such a threat was seen by some in the new understanding of the relations between man and the rest of the living world. One may even remember the concern among the learned, that some of the fundamental developments of physics; the theory of relativity, and even more, the ideas of complementarity and their far-reaching implications on the relations of common sense and of scientific discovery, their enforced reminder, familiar to Hindu culture but rather foreign to that of Europe, of the latent inadequacies of human conceptions to the real world they must describe.

One may think of these things, and especially of the great conflicts of the Renaissance, because they reflect the truth that science is a part of the world of men; that often before it has injected into that world, elements of instability and change, that if there is peril in the situation today -- as I believe there is -- we may look to the past for reassurance that our faith in the value of knowledge could prevail.

An atomic bomb is not a new conception, a new discovery of reality. It is a very ordinary thing in some ways, compact with much of the science that makes our laboratories and our industry. But it will change menís lives as over the centuries, the knowledge of the solar system has changed them. For in a world of atomic weapons, wars will cease.

And that is not a small thing. Not small in itself, as the world knows today, perhaps more bitterly than ever before, but perhaps in the end, even greater in the alterations, the radical, if slow, alterations in the relations between men and between nations and cultures that it implies.

It can only help us, I believe, to recognize these issues as rather great issues. We can serve neither ourselves, nor the cause of the freedom and growth of science, or our fellow men if we underestimate the difficulties, or if we through cowardice, becloud the radical character of the conflict and its issue.

During our lifetime, perhaps atomic weapons could be either a greater or small trouble. They cannot be a small hope; they can be a great one. Sometimes, when men speak of the great hope and the great promise of the field of atomic energy, they speak not of peace, but of atomic power and of nuclear radiations.

Certainly, these are proper enthusiasms, enthusiasms that we must all share. The technical feasibility of deriving virtually unlimited amounts of power from controlled nuclear reactors, seems very certain; very nearly certain. And the realization of plants to demonstrate the advantages and limitations of such power does not seem, from the point of view of technical effort, remote.

One must look at history to learn that such possibilities will, in time, be found of value; will, in time, come to play an important -- even if at this moment not thoroughly understood, part in our industry and our economy. You have heard this morning of some of the biological and medical problems and uses of radiation from such reactors. Even physicists can think of some instructive things to do with the grams of neutrons such reactors make available.

And all of us, who have seen something of the growth of science, know very well that what we can discern of the possibilities in these fields is a very small part of what will turn up when we really get into them.

Nevertheless, it would seem somewhat wrong to me to let our confidence -- and mind you, our wholly justified confidence -- in the future of the peaceful applications of nuclear physics distract us entirely from the immediacy and the peril of atomic weapons. It would not be honest to do so, for not even a better understanding of the physical world, not even the most welcome developments of therapy should make us content to see these weapons turn to the devastation of the earth.

It will not even be very practical to do so. Technically, the operation of reactors and the manufacture of weapons are rather closely related. Wherever reactors are in operation, there is a potential source, though not necessarily a convenient one, of materials for weapons. Wherever materials are made for weapons, they can be used for reactors that may be well suited to research for power development.

It would seem to me almost inevitable that in a world committed to atomic armament, the shadow of fear, secrecy, constraint and guilt, would hang heavy over much of nuclear physics, much of science. Scientists in this country have been quick to sense this, and to attempt to escape it. I do not think that this attempt can be very successful in a world of atomic armament.

There is another set of arguments whose intent it is to minimize the impact of atomic weapons, and thus to delay or to avert the inevitability in the end, radical changes in the world, which their advent would seem to require. There are people who say that they are not such very bad weapons.

Before the New Mexico test, we sometimes said that, too, writing down square miles and equivalent tonnages and looking at the pictures of a ravaged Europe. After the test, we do not say it anymore. Some of you will have seen photographs of the Nagasaki strike, seen the great steel girders of factories twisted and wrecked. Some of you may have noticed that these factories that were wrecked were many miles apart. Some of you will have seen pictures of the people who were burned, or had a look at the wastes of Hiroshima.

That bomb at Nagasaki would have taken out ten square miles, or a bit more, if there had been ten square miles to take out. Because it is known that the project cost two billion dollars and we dropped just two bombs, it is easy to think that they must be very expensive. But for any serious undertaking in atomic armament, and without any elements of technical novelty whatever, just doing things that have already been done, that estimate of cost would be high by something like a factor of a thousand.

Atomic weapons, even with what we know today, can be cheap. Even with what we know how to do today without any of the new things, the little things and the radical things, atomic armament will not break the back of any people that want atomic armament.

The pattern of the use of atomic weapons was set at Hiroshima. They are weapons of aggression, of surprise, and of terror. If they are ever used again, it may well be by the thousands, or perhaps by the tens of thousands. Their method of delivery may well be different and may reflect new possibilities of interception, and new efforts to outwit them. And the strategy of their use may well be different than it was against an essentially defeated enemy.

But it is a weapon for aggressors, and the elements of surprise and of terror are as intrinsic to it as are the fissionable nuclei. One of our colleagues, a man most deeply committed to the welfare and the growth of science, advised me not long ago not to give too much weight in any public words, to the terrors of atomic weapons as they are, and as they can be.

He knows as well as any of us, how much more terrible they can be made. It might, he said, cause a reaction hostile to science. It might turn people away from science. He is not such an old man, and I think it will make little difference to him, or to any of us, what is said now about atomic weapons if before we die, we live to see a war in which they are used.

I think that it will not help to avert such a war if we try to rub the edges off this new terror that we have helped bring to the world. I think that it is for us among all men, for us as scientists perhaps in greater measure, because it is our tradition to recognize and to accept the strange and the new. I think it is for us to accept as fact, this new terror, and to accept with it the necessity for those transformations in the world which will make it possible to integrate these developments into human life.

I think we cannot, in the long term, protect science against this threat to its spirits and this reproach to its issue, unless we recognize the threat and the reproach, and help our fellow men in every way suitable to remove their cause; their cause is war.

If I return so insistently to the magnitude of the peril, not only to science but to our civilization, it is because I see in that our one great hope as a further argument against war, like arguments that have always and increasingly existed, that have grown with the gradual growth of modern technology, it is not unique.

As a further matter requiring international consideration, like all other matters that so require it, it is not unique. But as a vast threat and a new one, to all the peoples of the earth, thatís novelty, itís terror, its strangely promethean quality, it has become in the eyes of many of us, a unique opportunity.

It has proven most difficult to make those changes in the relations between nations and peoples. Those concurrent and mutually dependent changes in law, in spirit, in customs and in conception; theyíre all essential. No one of them is absolutely prior to the others that should make an end to war. It has not only been difficult, it has proven impossible. It will be difficult in the days ahead, difficult and beset with discouragements and frustrations, and it will be very slow, but it will not be impossible.

If it is recognized as I think it should be recognized, that this for us in our time is the fundamental problem of human society, and it will not be impossible. These are very major commitments, nor would I minimize their depth, for they involve holding prior to all else we cherish all that we would live for and die for. Our common bond with all people everywhere, our common responsibility for a world without war, our common confidence that in a world thus united, the things that we cherish, learning and freedom and humanity, will not be lost.

These words may seem visionary, but they are not meant so. It is a practical thing to avert atomic war. It is a practical thing to recognize the fraternity of the peoples of the world. It is a practical thing to recognize as a common responsibility, wholly incapable of unilateral solution, the completely common peril that atomic weapons constitutes for the world. To recognize that only by community of responsibility is there any hope of meeting that peril.

It could be an eminently practical thing to attempt to develop those arrangements, and that spirit of confidence between peoples that are needed for the control of atomic weapons. It could be practical to regard this as a pilot plant for all those other necessary international arrangements, without which there will be no peace.

For this is a new field, less fettered than most with vested interest, or with the vast inertia of centuries of purely national sovereignty. This is a new field growing out of a science inspired by the highest ideals of international fraternity. It would seem somewhat visionary and more than a little dangerous to hope that work on atomic energy and atomic weapons might proceed, as have so many things in the past. Like the building of battleships on a purely and narrowly national authority, without basic confidence between peoples, without cooperation or the abrogation that somehow these separate, distrustful atomic arsenals would make for the peace of the world.

It would seem to me visionary in the extreme, and not practical, to hope that methods which have so sadly failed to avert war in the past, will succeed in the face of this far graver peril. It would, in my opinion, be most dangerous to regard, in these shattering times, a radical solution as less practical than a conventional one. It would also be most dangerous and most certain to lead to tragic discouragements to expect that a radical solution can evolve rapidly, or that its evolution will be free of the gravest conflicts and uncertainties.

The first steps in implementing the internationalization of responsibility, of responsibility perhaps in the first instance for averting the perils of an atomic war, will inevitably be very modest. It is surely not proper for me, who have neither experience nor knowledge, to speak of what such steps might be.

But there are two things that perhaps might be borne in mind that we might wish to say as scientists. One is that not only politically, but technically, this field of atomic energy is a very new field, and a very rapidly changing one. That it would be well to stress the interim, tentative character of any arrangements that might in the near future, seem appropriate.

The second is that in the encouragement and cultivation of the exchange between nations, we would see not only an opportunity for strengthening the fraternity between scientists of different lands, but a valuable aid in establishing confidence among the nations as to their interests and activities in science, generally, and in the fields bearing on atomic energy in particular.

It is not at all as a species; it is rather a concrete and constructive, if limited, form of those relations of cooperation among nations which must be the pattern of the future. Let me say again, these remarks are not intended in any way to define or exhaust the content of any international arrangements it may be possible or appropriate to make, nor to limit them. They are offered as suggestions that occur naturally to a scientist who would wish to be helpful. But they leave quite untouched, the basic problems of statesmanship on which all else depends.

There will have been little in these words that can have been new to anyone. For months now, there has been among scientists, as well as many others, a concern; often a most confusingly articulate concern, both for the critical situation in which nuclear physics finds itself, and for the more general dangers of atomic war.

It seems to me that these reactions among scientists that have caused them to meet and speak and testify and write and wrangle without remission, and that are general almost to the point of universality, reflect -- correctly reflect an awareness of unparalleled crisis. It is a crisis because not only the preferences and tastes of scientists are in jeopardy, but the substance of their faith; the general recognition of the value, the unqualified value of knowledge, of scientific power and progress.

Whatever the individual motivation and belief of the scientist, without that recognition from his fellow men of the value of his work, in the long term, science will perish. I do not believe that it will be possible to transcend the present crisis in a world in which the works of science are being used, that theyíre being knowingly used for ends men hold evil.

In such a world, it will be of little help to try to protect the scientist from restraints, from controls, from an imposed secrecy which he rightly finds incompatible with all he has learned to believe and to cherish. Therefore, it does seem to me, necessary to explore somewhat the impact of the advent of atomic weapons on our fellow men, and the courses that might lie open for averting the disaster they invite.

I think there is only one such course, and that in it lies the hope of all our futures.

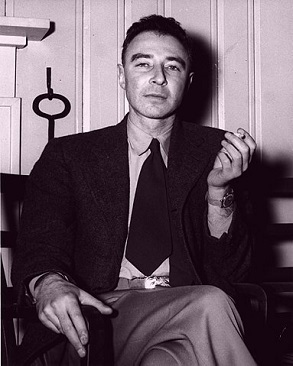

Image Source: Wikipedia.org

Page Updated: 8/4/18

U.S Copyright Status: Text = Uncertain. Image = Public domain.