Mr. Bossert: Good morning, all. Sorry for being a little tardy this morning. Iíd like to talk to you today about a cyber issue of significance.

In May of this year, a dangerous cyberattack known as WannaCry spread rapidly and indiscriminately across the world.

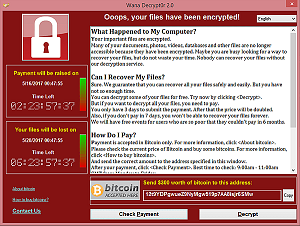

The malware encrypted and rendered useless hundreds of thousands of computers in hospitals, schools, businesses, and homes in over 150 countries. While victims received ransom demands, paying those demands did not unlock their computers.

This was a careless and reckless attack. It affected individuals, industry, governments. And the consequences were beyond economic. The computers affected badly in the UK and their healthcare system put lives at risk, not just money.

After careful investigation, the United States is publicly attributing the massive WannaCry cyberattack to North Korea. We do not make this allegation lightly. We do so with evidence, and we do so with partners.

Other governments and private companies agree. The United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Japan have seen our analysis, and they join us in denouncing North Korea for WannaCry.

Commercial partners have also acted. Microsoft traced the attack to cyber affiliates of the North Korean government, and others in the security community have contributed their analysis.

The stability of the Internet and the security of our computers is vital to free and fair trade and the fundamental principles of our liberty. And accountability and cooperation are the cornerstone principles of our cybersecurity strategy.

North Korea has acted especially badly, largely unchecked, for more than a decade. Many of you have reported on that. Its malicious behavior is growing more egregious, and stopping that malicious behavior stops with this step of accountability.

The attribution is a step towards holding them accountable, but itís not the last step. Addressing cybersecurity threats also requires governments and businesses to cooperate to mitigate cyber risk and to increase the cost to hackers by defending America. The U.S. will lead this effort.

President Trump has rallied allies and responsible tech companies around the free world to increase the security and resilience of the Internet. Cooperation between industry and good governments will bring improved security, and we can no longer afford to wait.

We applaud our corporate partners, Microsoft and Facebook especially, for acting on their own initiative last week without any direction by the U.S. government or coordination to disrupt the activities of North Korean hackers. Microsoft acted before the attack in ways that spared many U.S. targets.

Last week, Microsoft and Facebook and other major tech companies acted to disable a number of North Korean cyber exploits and disrupt their operations as the North Koreans were still infecting computers across the globe. They shut down accounts the North Korean regime hackers used to launch attacks and patched systems.

Iím extremely proud of the hard and dedicated work of the intelligence services and cybersecurity professionals. And Iím very happy today to have one of the finest with me.

Iíd like to introduce Jeanette Manfra, Assistant Secretary for Cybersecurity and Communications at DHS. We call today -- I call today, and the President calls today, on the private sector to increase its accountability in the cyber realm by taking actions that deny North Korea and the bad actors the ability to launch reckless and disruptive cyber acts.

As responsible U.S. companies join us in this cooperation, it will fall to Jeanette and her leadership team -- Chris Krebs, Secretary Nielsen. Theyíre in charge, literally, of coordinating the operations that will protect us.

As we make the Internet safer, we will continue to hold accountable those who harm us or attempt to threaten us, whether they act alone or on behalf of criminal organizations of hostile nations.

With that, I turn it over to Jeanette. Thank you.

![]()

Assistant Secretary Manfra: Thank you, sir.

At DHS, cybersecurity is a core mission of ours. And just like preventing terrorism or responding to hurricanes and wildfires, it is a shared responsibility between government, industry, and the American people.

WannaCry is a great example of how this partnership works. It began on May 12th, the Friday before Motherís Day. We first learned that something unusual was happening from our partners in the Asia-Pacific region. As the malware traversed the globe, we received information from our partners in Europe. As the day went on and the National Health Service in the U.K. was impacted, we knew we were dealing with a serious issue, and began to activate our domestic-industry partnership.

By midafternoon, I had all of the major Internet service providers either on the phone or on our watch floor sharing information with us about what they were seeing globally and in the United States. We partnered with the Department of Health and Human Services to reach out to hospitals across the country to offer assistance. We engaged with federal CIOs across our government to ensure that our systems were not vulnerable. I asked for assistance from our partners in the IT and cybersecurity industry. And by 9:00 p.m. that night, I had over 30 companies represented on calls, many of whom offered us analytical assistance throughout the weekend.

By working closely with these companies and the FBI throughout that night, we were able to issue a technical alert, publicly, that would assist defenders with defeating this malware. We stayed on alert all weekend but were largely able to escape the impacts here in this country that other countries experienced.

In many ways, WannaCry was a defining moment and an inspiring one. It demonstrated the tireless commitment of our industry partners, a moment that showed how the government and private sector got it right; that our preparation, our investments in cybersecurity, keeping our systems up to date, and sharing information paid off.

Although the WannaCry attack demonstrated our national capability to effectively operate and respond, we cannot be complacent. We are seeing increased activity and sophistication from both nation-states and non-state actors. In many instances, these are the same adversaries we have faced in the past. They are just now operating in a different space.

Most devices are connecting to the Internet, which broadens the threat landscape and compounds the challenge for security practitioners. And there is no sign of these trends abating in the years to come. This is why cybersecurity continues to be one of the most significant and strategic risks to the United States.

In addition to broadening the threat landscape, we see some gaps between what an entity might consider adequate security for themselves or their sector and what is in the publicís interest. The American people depend upon critical services and functions, such as electricity, a stable financial system, and dependable communications -- all things that enable our modern way of life. Many of these are run by the private sector.

Therefore, in order to ensure the security of these services and functions, we rely heavily on public-private collaboration. This collaboration is entirely voluntary and provides companies with strong liability and privacy protections should they participate.

To ensure adequate security in the private sector, DHS plans to move beyond only offering voluntary assistance to more proactively becoming the world leader in cyber risk analysis and intervening directly with companies when necessary.

Specific to North Korea, we have issued technical alerts to assist network defenders in understanding the types of malware that theyíre using, and urge them to remove them from their systems so that they cannot continue to have access to our infrastructure. As we learned during the WannaCry attack, these incidents can have life-threatening consequences.

So how did we get here? The Internet was engineered for interoperability, trust, and openness. Innovation and automation equals efficiency and cost savings, but oftentimes the cost of security, which is too commonly an afterthought or bolted on after-market. Attackers only have to be right once but defenders have to be right all the time.

Some say that defending cyberspace is impossible and that attacks are inevitable. I disagree with this assumption. We can take small tangible actions to make the cyber ecosystem safer. Our goal is a cyber environment where a given threat, such as a malicious e-mail, can only be used once before it is blocked by all other potential victims.

We need to get the advantage to the defender. We make it way too easy for attackers by operating independently. Our adversaries are not distinguishing between public and private, so neither should we. Government and industry must work together now more than ever if we are serious about improving our collective defense. We cannot secure our homeland alone. A company canít single-handedly defend itself against a nation-state attacker. Cybersecurity is a shared responsibility. We all play a part in keeping the Internet safe.

To prevent another attack like WannaCry, we are calling on all companies to commit to the collective defense of our nation. And this commitment does not end on our borders. As identified in the WannaCry incident, cybersecurity defense is a global challenge. As many as 150 countries had systems infected by this ransomware. And it is only through international partnerships that the United States had time to prepare.

Therefore, we are working to strengthen our international partnerships with cybersecurity centers across the world. We are taking a greater leadership role in cybersecurity at DHS. We seek to drive the market toward more secure, scalable, and interoperable solutions. Ahead of us lie great challenges, but even greater opportunities, which I know we can accomplish by working together.

Thank you very much.

![]()

Mr. Bossert: Thanks, Jeanette. Questions? Sir.

Question: Two questions. The United States was apparently a bit slow to publicly identify North Korea at the culprit in all of this. Was there some new evidence that came to the fore that led to making the public conclusion?

The second question is about Marcus Hutchins, whoís been identified as an individual who helped out to stop the WannaCry. Whatís going to happen to him, given the fact that heís been locked up on unrelated charges? Will the U.S. intervene?

Mr. Bossert: So, two questions there. One, did we do it too slowly? No. My answer is, no. I think the most important thing is to do it right and not to do it fast. We took a lot of time to look through classified, sensitive information. What we did was, rely on -- and some of it I canít share, unfortunately -- technical links to previously identified North Korean cyber tools, tradecraft, operational infrastructure. We had to examine a lot. And we had to put it together in a way that allowed us to make a confident attribution.

As we move forward and attribution becomes part of our accountability pillar, we canít do it wrong. We canít get it wrong. We canít try to rush it. I think ultimately, at this point, if we had gotten it wrong, it would have been more of a damage to our reputation and national security than it would have been a boom for us to do it quicker.

The second question, I canít comment on the ongoing criminal prosecution or judicial proceedings there. But I will note that, to some degree, we got lucky. In a lot of ways, in the United States we were well-prepared. So it wasnít luck -- it was preparation, it was partnership with private companies, and so forth. But we also had a programmer that was sophisticated, that noticed a glitch in the malware, a kill-switch, and then acted to kill it. He took a risk, it worked, and it caused a lot of benefit. So weíll give him that. Next time, weíre not going to get so lucky.

So what weíre calling on here today is an increased partnership, an increased rapidity in routine speed of sharing information so that we can prevent patient zero from being patient 150.

Question: You said that cyber affiliates within the North Korean government were responsible for this. North Korea is a fairly reclusive country. How do you believe, generally, that their cyber operations and their hacking operations work? How does that all piece together, in your mind, from what youíve been able to tell? And secondly, you talk about wanting the private sector to do more. Exactly what do you want to see out of the private sector?

Mr. Bossert: So the difficulty in attribution is often to figure out who is operating the keyboard and on whose behalf. And so those are the two biggest challenges. People operating keyboards all over the world on behalf of a North Korean actor can be launching from places that are not in North Korea. And so thatís one of the challenges behind cyber attribution.

Weíre comfortable in this case, though, that is was directed by the government of North Korea. Weíre also comfortable in saying that there were actors on their behalf, intermediaries, carrying out this attack, and that they had carried out those types of attacks on behalf of the North Korean government in the past. And that was one of the tradecraft routines that allowed us to reach that conclusion.

That said, how they operate is often a little mysterious. If we knew better, with perfect knowledge, we would be able to address the North Korean problem with more clarity. And part of the larger strategy of increased pressure on North Koreans is to get them to change that behavior.

I mean, my observation: Theyíve got some smart programmers. Itís a real shame that their government is leading them down -- the use of that -- in the wrong direction. If they have smart people there and a free government, they would be positive contributors to the world. I wish that their leadership and despots would get out of the way.

Question: So do you think they outsource the majority of these operations? Or do you think this comes from within the actual borders and the actual government of North Korea itself?

Mr. Bossert: Yeah, I donít think thereís an outsourcing distinction here with the North Korean regime. I think that everything that happens in North Korea happens with, and by, the direction of their leadership.

Question: And on the private sector, you want to see them do more?

Mr. Bossert: The private sector -- What weíre doing here is improving our own ability to work with them. So thereís two halves to this. Remember that what they do is they report to us all the targeted attack vectors that theyíre seeing. We put it together and share it back out with everybody. So if youíre receiving a phishing attack and you report it to us, we can notify the whole country to be on the lookout for that.

So we want them to increase their sharing of information with us. And then, as we move forward and become more sophisticated in this Administration, weíre going to ask them to look into sharing more technical information on how theyíre architected and where their exposure points are so we can get a better strategic view of defending ourselves.

Question: Tom, the purpose of ransomware is to raise money. So do you have a sense now of exactly how much money the North Koreans raised as a result of this? And do you have any idea what they did with the money? Did it go to fund the nuclear program? Did it go just to the regime for its own benefit? Or where did that money go?

Mr. Bossert: Yeah, itís interesting. Thereís two conundrums here. First, we donít really know how much money they raised, but they didnít seem to architect it in the way that a smart ransomware architect would do. They didnít want to get a lot of money out of this. If they did, they would have opened computers if you paid. Once word got out that paying didnít unlock your computer, the payment stopped.

And so I think that, in this case, this was a reckless attack and it was meant to cause havoc and destruction. The money was an ancillary side benefit. I donít think they got a lot of it.

Question: Two things. First, Tom, was is the consequence for this? I understand that we have to have a collective defense of our nation. What is the consequence to North Korea for doing this?

Mr. Bossert: Well, at this point, North Korea has done everything wrong as an actor on the global stage that a country can do. And President Trump has used just about every lever you can use, short of starving the people of North Korea to death, to change their behavior. And so we donít have a lot of room left here to apply pressure to change their behavior.

Itís, nevertheless, important to call them out to let them know that itís them and we know itís them. And I think, at this point, some of the benefit that comes from this attribution is letting them know that weíre going to move to stop their behavior. It also allows us to galvanize -- back to the question previously -- the private sector. In this case, the private sector also acted. Facebook took down accounts that stopped the operational execution of ongoing cyberattacks. And Microsoft acted to patch existing attacks, not just the WannaCry attack initially.

So this is allowing us to call on all likeminded and good, responsible companies to stop supporting North Korean hackers, whether theyíre operating in North Korea or elsewhere.

And itís, secondarily, an opportunity for us to call on the other countries in the region that were affected to mobilize them to stop that same behavior. Often, North Koreans can travel outside of North Korea to hack, or they can rely on people outside of the country with better access to the Internet to carry out this malicious activity. And we need other countries, not just other companies, to work with us.

Question: So then to follow up on this, it seems like thereís a different handling of different intelligence assessments. First, on North Korea, thereís an elaborate rollout here today where youíre calling out North Korea by name for its cyber activities. But take Russia, for example, for interfering in the U.S. election. Why hasnít there been a similar rollout like this to call Russia out for its activities?

Mr. Bossert: Iím not sure this is all that elaborate, but Iíll tell you that there was. I think President Obama called them out. And I think, for what itís worth and underreported, President Trump not only continued the national emergency for cybersecurity, but he did so himself and sanctioned the Russians involved in the hacks of last year.

And so I think that that was the appropriate act. I think heís continued that for another year and will probably continue for that year after that.

Question: Have all the sanctions been implemented?

Mr. Bossert: This was -- yeah, this was the Continuation of the National Emergency with Respect to Significant Malicious Cyber-Enabled Activities. President Trump continued that national emergency, pursuant to the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, to deal with the ďunusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States.Ē

Now, look, in addition, if thatís not making people comfortable, this year we acted to remove Kaspersky from all of our federal networks. We did so because having a company that can report back information to the Russian government constituted a risk unacceptable to our federal networks.

In the spirit of cooperation, which is the second pillar of our strategy -- accountability being one, cooperation being the second -- weíve had providers, sellers, retail stores follow suit. And weíve had other private companies and other foreign governments also follow suit with that action.

I think weíre leading to take bad actors -- whether they be Russia, North Korea, at times China and Iran -- off the Internet and knocking them off their game. And I think today is about North Korea, but I welcome the question on Russia. I think we stand with a good record.

Sir.

Question: Thanks, Tom. I have a follow-up on that and a separate question. The President has said -- sort of casting doubt on the findings about Russian interference -- he said, unless you catch the hackers in the act, itís very hard to know exactly who is behind it.

Mr. Bossert: Very true.

Question: Did the U.S. catch the North Koreans in the act on this?

Mr. Bossert: Yeah, thatís the key here, right? So today, it took us a little while, but we did it in a thoughtful manner because we believe now we have the evidence to support this assertion. Itís very difficult to do when youíre looking for individual hackers or different groups. In this case, we found a concerted effort.

Question: And then, secondly, you mentioned earlier that North Korea has acted especially badly and, you said, largely unchecked for the last decade. Now thereís been reporting that the U.S. has actually acted to combat North Korean interference; weíve taken actions, reportedly, against their nuclear facilities, in terms of using our own capabilities. Obviously, none of that is being confirmed on the record, but when you say largely unchecked, doesnít that sort of undermine the idea that the U.S. has actually taken action to combat what North Korea is doing?

Mr. Bossert: No, I think President Trump has made it very clear that his view is that previous Administrations of both parties could have done more and should have done more, in his opinion, to apply more pressure on North Korea when the opportunity to do so might have resulted in a better world. And I think, at this point, the cyber issue has come on the heels of his other decisive actions. So it leaves us with little room left to apply additional pressure, but we will continue to apply that pressure campaign without any wavering.

David.

Question: Thanks very much for doing this. Can you take us a little more into your attribution process here? You said the leadership of North Korea ordered this. Thatís not something that would necessarily be visible from the code itself.

Mr. Bossert: Thatís right.

Question: Can you tell us a little bit about that within the limits of what you can, and whether you believe Kim Jong-un was directly involved in that decision? Can you also tell us a little bit about what you think the motive was? As you pointed out, ransom seemed to be sort of a cover story. Chaos -- I can see that, but thatís not the usual North Korea m.o.; they usually have something thatís a little more concentrated. And your map shows this is all over the place -- Indonesia, Japan. So tell us a little bit about that and how attribution got you to intent.

Mr. Bossert: Yeah, so let me go backwards on those, if you donít mind -- address them in reverse order. One of the difficulties here of this assertion is that it is wanton and reckless. And itís also one of the most troubling attributes of what weíve seen in WannaCry, and why itís so important for us to treat this one differently.

The idea here, David, is that what discriminates on the map is not the intent of the attacker, but the quality of the defenses and security of the people that they sought to attack. So the targets in the United States were harder, thanks to people like Jeanette. So they were suffering less.

People in Russia, people in China took this one badly. Some sectors in Great Britain took this one very badly, and so their computers werenít defended properly, in this case -- or at least in time; I shouldnít say ďproperly.Ē Weíre all struggling to keep up with this increasingly reckless behavior.

So I disagree that theyíre looking to be more targeted and more sober in their calculus. I think at this point, North Korea has demonstrated that they want to hold the entire world at risk, whether it be through a nuclear missile program or through wanton cyberattacks.

Secondly, itís a little tradecraft, to get to your second question. Itís hard to find that smoking gun, but what weíve done here is combined a series of behaviors. Weíve got analysts all over the world, but also deep and experienced analysts within our intelligence community that looked at not only the operational infrastructure, but also the tradecraft and the routine and the behaviors that weíve seen demonstrated in past attacks. And so you have to apply some gumshoe work here, not just some code analysis.

Question: Had they not been able to take advantage of the vulnerabilities that got published in the Shadow Brokers website, do you think that would have made a significant difference in their ability to carry out the attack?

Mr. Bossert: Yeah. So I think what Dave is alluding to here is that vulnerabilities exist in software. Theyíre not -- almost never designed on purpose. Software producers are making a product, and theyíre selling it for a purpose. When we find vulnerabilities, the United States government, we generally identify them and tell the companies so they can patch them.

In this particular case, Iím fairly proud of that process, so Iíd like to elaborate. Under this Presidentís leadership and under the leadership of Rob Joyce, whoís serving as my deputy now and the cybersecurity coordinator, we have led the most transparent Vulnerabilities Equities Process in the world.

And what that means is the United States government finds vulnerabilities in software, routinely, and then, at a rate of almost 90 percent, reveals those. They could be useful tools for us to then exploit for our own national security benefit. But instead, what we choose to do is share those back with the companies so that they can patch and increase the collective defense of the country. Itís not fair for us to keep those exploits while people sit vulnerable to those totalitarian regimes that are going to bring harm to them.

So, in this particular case, Iím proud of the VEP program. And Iíd go one step deeper for you: Those vulnerabilities that we do keep, we keep for very specific purposes so that we can increase our national security. And we use them for very specific purposes only tailored to our perceived threats. I think that theyíre used very carefully. They need to be protected in such a way that we donít leak them out and so that bad people can get them. That has happened, unfortunately, in the past.

But one level even deeper. When we do use those vulnerabilities to develop exploits for the purpose of national security for the classified work that we do, we sometimes find evidence of bad behavior. Sometimes it allows us to attribute bad actions. Other times it allows us to privately call -- and weíre doing this on a regular basis, and weíre doing it better and in a more routine fashion as this Administration advances -- weíre able to call targets that arenít subject to big rollouts. Weíre able to call companies, and weíre able to say to them, ďWe believe that youíve been hacked. You need to take immediate action.Ē It works well; we need to get better at doing that. And I think that allows us to save a lot of time and money.

So that process is an equities balancing process. I think weíve got it right. And I know the United States is, by far, head and shoulders above any other country in the world.

Maíam.

Question: Two things. One, on a matter of policy, is this Administrationís policy that an attack on a U.S. company constitutes an attack on the U.S. government? How did you get to that conclusion that itís -- youíre clearly holding the state of North Korea responsible here. So can you explain that policy?

And then on digital currency, I believe -- I know you said not much money was raised off this, you donít think -- but that seems to be sort of an open space since that does appear to be how the hackers were seeking any compensation.

Mr. Bossert: Right.

Question: What are you doing on that?

Mr. Bossert: Yeah, so any cryptocurrency might be difficult to track, so itís both a good and a positive innovation, but also a concern, as we hope it doesnít end up being used for illicit behavior.

In this particular case, our assumption on them not raising a lot of money comes from our belief that the hackers hit targets that then reported to us what they did about it. The targets seem to have reported to us, by and large, that they mostly didnít pay. Some seemed to have tried to pay and then quickly reported to others online and through other media that they werenít getting their computers unlocked, and so the others stopped paying. Does that make sense?

So we were able to track the behavior of the targets in that case.

Question: But without that report, you would not have necessarily had visibility into how this cryptocurrency was being used or manipulated?

Mr. Bossert: Yeah, Iím going to reserve judgment on that. It is a difficulty that, as a general matter, Iím not sure how we would have tracked a cryptocurrency into this particular country. So Iíll have to get back on that.

But I will say that your last question is open -- itís not about holding a country accountable; itís about simple culpability. Weíve determined who was behind the attack and weíre saying it. Itís pretty straightforward. Itís, "All Iíve learned about cybersecurity, I learned in kindergarten."1

Weíre going to hold them accountable, and weíre going to say it. And weíre going to shame them for it. And when we need to increase our collective defenses, weíre going to cooperate and weíre going to try to trust each other more. And I think companies are demonstrating that trust. I think this President is inspiring that kind of trust. I think heís bringing them together in a way thatís got them feeling like weíre on their side. And I think itís going to improve our security.

Question: Is that why, in this case, youíre saying an attack on U.S. companies constitutes an attack on the U.S. government?

Mr. Bossert: Iím not saying that.

Question: Thatís not the policy? And youíre not moving in that direction to make that policy?

Mr. Bossert: Thatís not the policy right now, no.

Question: How do you expect North Korea to respond after --

Mr. Bossert: Iím sorry, can you say it again?

Question: Yes. How do you expect North Korea to respond after this announcement?

Mr. Bossert: I hope that they decide to stop behaving badly online. Iím not naÔve, and I think theyíll probably continue to deny and to continue to believe that theyíre beyond repercussions and beyond consequences. But I think, at some point, theyíre going to realize that this President and this country, and the allies that heís rallied unanimously around this cause, will bring them to change their behavior.

And if they donít, this President is going to act on behalf of the United States and its national security interests, and not the national security interests of another country. I think heís been clear on that, and Iím glad heís our President in that regard.

Question: Can you say how the President initially interpreted these findings -- how many times he was briefed? Was he receptive or did he have any doubts? And then, secondly, Senator Lindsey Graham says thereís a 30 percent chance that the President will act to strike North Korea. And if they test another nuclear weapon, that jumps to 70 percent. Do you dispute Grahamís claims?

Mr. Bossert: Yeah, I have no ability to put a percentage on those outcomes. Iíd hate to do so. It doesnít seem productive for me to do so.

That said, the President is briefed regularly by the heads of his intelligence communities, and thatís how he received this information.

Sir.

Question: So you talked about the 90 percent of times when you guys share information back with companies rather than exploit those vulnerabilities. Was this one of the 10 percent that you guys had held onto?

Mr. Bossert: So I think thereís a case to be made for the tool that was used here being cobbled together from a number of different sources. But the vulnerability that was exploited -- the exploit developed by the culpable party here -- is the tool, the bad tool. But the underlying vulnerability in the software that they exploited predated and preexisted, I believe, our Administration taking power.

And so I donít know what they got and where they got it, but they certainly had a number of things cobbled together in a pretty complicated, intentional tool meant to cause harm that they didnít entirely create themselves. And part of that allowed us to attribute their behavior and their culpability here because we were able to look at where they got different parts and tied them together, and how they did so. And when they tied them together, they used their tradecraft and revealed their hand.

Question: I just want to follow up on that a little bit. One of the criticisms that came out in late May after this was that the NSA chose to hoard security holes in operating systems. Thatís been criticized by Microsoftís Brad Smith, even Vladimir Putin. Brad Smith writing, ďThis attack provides yet another example of why the stockpiling of vulnerabilities by governments is such a problem.Ē Youíre talking about private industry needing to step in information sharing, but how much is the U.S. government, specifically the NSA, to blame for this?

Mr. Bossert: No, not at all. And I think that, while the U.S. government needs to better protect its tools, and things that leak are very unfortunate and we need to apply security measures that prevent that from happening, I think Brad also now appreciates more and better what we hold on to and why we hold onto it. And, in part, he appreciates that more and better, because we made it a transparent process. Itís something that we addressed and changed under President Trumpís tenure. Itís something weíve rolled out. And while youíre quoting people that have criticized us, Iíll tell you back that even the ACL, complimented us for how well that process rolled out.

Question: But this isnít some small player. This is Microsoft. I mean, youíre talking about --

Mr. Bossert: Microsoft today -- Brad Smith is standing with me on this. Heíll stand with me on television if you need him to. Brad is a good partner for this country. And Brad has come out in this particular case and joined us in this attribution. So I think Microsoft is a strong partner. I have absolutely no fear that thereís any wedge between us.

Question: Okay, but you didnít really answer the question fully, like what Iím trying to get at. You havenít provided the assurance --

Mr. Bossert: I believe I did, so let me back up and tell you why I thought I did, maíam. I didnít mean to give you short shrift. The reason I thought I answered it already is in part because Mr. Sangerís question earlier touched on that process. So Iíll go back.

What Brad was talking about at that time, at the time that quote was made contemporaneous to that remark, was his belief that we were not adequately weighing the different equities in the process when we held onto tools, or vulnerabilities, that we discovered inside the government. Now he understands how that process works because weíve made it transparent and weíve opened it. At the time he made those comments, it was not an open and transparent process.

Question: So weíre still holding onto tools?

Mr. Bossert: As I said, we hold onto about 10 percent, give or take, of the vulnerabilities that we find for the purpose of national security exploitation.

Question: So how does that make the private industry feel comfortable this canít happen again if youíre still doing that and not providing 100 percent --

Mr. Bossert: We donít use them to attack anyone indiscriminately. We certainly didnít attack 150 countries and hundreds of thousands of computers. The North Koreans took a vulnerability, modified it into a weapon, and deployed it recklessly -- not the United States.

Iím going to wrap that --

Question: Last question.

Mr. Bossert: Can I go -- last question?

Question: Yeah, just one more follow-up to what Margaret had asked you about cryptocurrency while we have you have here. You said itís difficult to track. Sarah had told us a couple of weeks ago that you were monitoring it. What exactly is being monitored, and why are you monitoring it? What is the Administrationís position on this seemingly booming industry?

Mr. Bossert: Yeah, we donít have a formal position on block-chain currencies and cryptocurrencies at this point. Block-chain technologies operate in a way that thereís, I guess, great hope and promise. They also have some -- they also present some security risks and concern for us.

And so I think what Sarah meant to tell you is that I track and monitor this very closely from a security perspective, because among other things, Iím not only advising on cyber policy, but also on counterterrorism policy.

And so what we want to make sure is that block-chain cryptocurrencies arenít being used to support illicit behaviors in ways that we canít discover. But we have other people in the Administration equally following it for the promise it provides economically and from a trade perspective. So we donít have any negative or positive view on it right now, but we have to monitor it closely as this new technology is becoming quite, quite, I guess, expensive -- lucrative.

Question: Does it need regulation?

Mr. Bossert: Not prepared to say that now. Thank you.

Question: How many future trips to Puerto Rico -- are you guys [inaudible]?

Mr. Bossert: Iíll tell you what, Iíll give you a full briefing on Puerto Rico. I try to track it regularly. The Administration is tracking it regularly. And as for current trips, the Secretary of Homeland Security is there today, Kirstjen Nielson, with the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. Housing is a major challenge for us in Puerto Rico. The Governor is doing a great job, but heís got a large problem here as we move forward with 55 percent of his housing population in informal housing.

Question: Power too, obviously?

Mr. Bossert: Power is making strong recovery. Weíre up over, I think, 65 percent in terms of power restoration, which is 65 percent of the load capacity, which is a significant milestone. Weíre hoping to get to 70 by the end of the year. So weíll see how that tracks. Pretty close to what we set for ourselves in an aggressive target. But Puerto Rico is on my mind on a regular basis and the Presidentís as well. And he sent Kirstjen and Ben Carson down to see whatís happening.

Question: Thank you.

Mr. Bossert: Thank you. Thanks all.

Book/CDs by Michael E. Eidenmuller, Published by

McGraw-Hill (2008)

Book/CDs by Michael E. Eidenmuller, Published by

McGraw-Hill (2008)

1 An allusion to American author Robert Fulghum's book All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten, which promulgated and popularized the notion that the fundamental rules of good conduct acquired during childhood ought to be normative for adult behavior (including -- here, especially -- honesty and accountability).

See also: Tom Bossert's Initial Briefing on WannaCry Ransomware Attacks

Original Text Source: WhiteHouse.gov

Original Audio Source: C-SPAN.org

Original Image (WannaCry) Source:

Wikipedia.org

Audio Note: AR-XE = American Rhetoric Extreme Enhancement

Page Created: 12/22/17

U.S. Copyright Status: This text and audio = Property of AmericanRhetoric.com. Image = Public domain.