[Note: transcript accuracy check in progress]

Yo. [O]kay, I've just got to check and see whoís here. Mike Gould, where are you? Thank you for letting me be here, bud. I appreciate it. Sitting right next to Superintendent by the way is my wife, Betty. Betty, would you stand up real quick? Sheís a babe.

Right next to Betty are my great, great friends and really my family members, Glenn Pollack [ph] and his wife Reagan [ph], and a lot of other great Americans sitting in the middle row. Mike, thanks for the opportunity to be here. Rich Clark [ph], get your chin in. [Unclear at :53], thanks for the work youíre doing here. Dana [ph], thank you for allowing me to visit with you this morning. It was an honor as always. And Dr. Mew [ph], youíll always be a chemistry professor to me and you scare me to death. Itís great to see you again, my friend. Thank you for the members of the faculty who are here. Most importantly, thank you to the members of the cadet wing who are here. Thank you for volunteering for this session.

This picture has absolutely nothing to do with what Iím going to talk about, but it reminds me that I was cool once. Now, Iím just old and dumpy. Makes me seem like a loser, doesnít it? And youíre stuck with me for the next 45 minutes. Donít clap, yet. I might suck.

Next slide, please.

One of the things thatís cool about coming back to the Air Force Academy is that Iím always reminded of things that I didnít appreciate when I was a cadet. Donít take this as a lecture. Take this as a suggestion. Places like the Honor Court. Have you ever been up there in the evening when nobody else is around? Donít have to answer this. If you havenít, go there then -- not when all those old guys are crying during the award ceremonies and opening a new plaques -- because you wonít really understand that unless you go there alone, and stand next to this B-20 or B-17 model here and look back over your shoulder at that P-40 and put your hand on the marble and close your eyes. Strange things happen. Youíll hear the "bogey" calls. Then youíll hear the "bandit" calls. Youíll hear the waist gunners testing their guns. Youíll sense the tension as they anticipate the attack. Youíll sense the fear; and youíll feel the pride. This is a magic place. Give it a try.

Next slide.

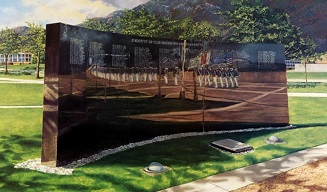

Hereís another magic place that I never really appreciated. You walk by it every day, right there by the flagpole. Sometime, just walk up to it when nobody's around; just stare into the stone. Put your hand on it and then send me an email and tell me you felt like you were alone -- because you wonít. First time I did this, when I moved my hand, there was a name there Iíve never seen before. It was Robert Lodge. Anybody heard of him?

Next slide.

I went and looked him up. There he is. Good looking doolie, huh? Mature, charismatic to a degree -- and then the right hand picture is him as a Captain. Robert Lodge is a member of the class of '64; graduated from second squadron, which I got the chance to visit this morning.

Next slide.

Before he died on his second combat tour, Robert Lodge earned five Silver Stars, seven Distinguished Flying Crosses, and 37 Air Medals, along with a Purple Heart. He shot down his last of his three MiGs on the day that Steve Richie shot down his first. Richie was one of the wingmen in -- in Robert Lodge's foreship. Unfortunately, as he attacked the MiG-21 to try and get it off the butt of one of his flight mates, a MiG-19 joined the fight and shot him down. His back-seater got out but he didnít. Robert Lodge is part of your Air Force heritage. Why donít we know about him? Visit the wall. Pick a name. Learn something about who you are.

| Air Force Academy Static displays include the F-4 flown by Colonel Richie, Vietnam Ace, F-105 Thunderchief, Cadet Chapel, Eagle/Fledgling statue, Honor Wall. |

Next slide.

You probably donít know who these guys [are] either. These are airmen. They're not U.S. airmen and they donít fly a lot except to get to the target, but theyíre really good at what they do. How many of you in the last seven days have said, "This place sucks"? Tell me the truth. Thereís still the Honor Code. Could be a lot worse. These guys could be looking for you. You know, when people hear that these guys are airmen, they just think "Man, warfare has changed."

Next slide, please.

It has changed. Let me run a video that many of you have probably seen, but before I run it, let me talk to you about it. This is an F-16 story. It's in Ramadi, Iraq, probably seven, eight years ago. The F-16 pilot's on station to support a special operator on the ground who's lasing a target for him. The target is just above that gun cross. Itís the big square building, because thereís a meeting of militant leaderships going on in there in the middle of Ramadi that was reported by a CIA source, and weíre going to take it out. Now as you start to hear the conversation between the soldier on the ground and the guy in the air, youíll hear him talk about a group of civilians that comes out of that building, turns on that road going down to the bottom of the picture. Theyíre heading to reinforce a gunfight going on with U.S. Army soldiers down to the south.

Let's run the video. [Videotape rolls]

See the people coming out -- down the road? Now I donít know those people. Theyíre bad guys. Guy in the ground knows that. Theyíre also brothers and fathers and husbands and sons, next door neighbors, friends and family members. Only other thing I know about them is that they have about eight seconds to live. Yeah. "Oh, dude." [repeating the voice on the video] Every now and then, remind yourself about why youíre here, why youíre really here, why you wear these things. Youíre joining the professional arms. Your job will be an ugly one. Thereís nothing pretty about what you just saw. Thereís nothing glorious about it. Thereís nothing cool about it. Itís ugly, but somebodyís got to be good at it. Mike Gould is. Harpo Clark is. I am. You better be. This is where you get ready.

Next slide.

You know, warfare may be changing, but -- letís run the video, Fred -- some things donít. [Videotape rolls] Except for the way they killed him, I donít think this scene looks much different that it would have looked a thousand years ago.

Next slide.

This picture was taken in Afghanistan 2002. It's an Air Force Master Sergeant named Bart Decker who's now retired. He's an Air Force Combat Controller and he went into Afghanistan with the First Army Special Forces teams to work with the Northern Alliance and fight the Taliban. As warfare has changed, technology has taken over. Weíve all heard that, right? Bart Decker is a new age kind of guy. He understands technology and heís got a boatload of it on that horse. But the most sophisticated piece of war fighting equipment in this picture is Bart Decker, and he really hasnít changed that much since the days of the Roman legion. Politics are going to change. Technology is going to change. The enemy will change -- next slide, Fred -- but they wonít. You know, our nation gives us its -- its sons and daughters, and it commits us to defending the nation and its interests and it expects us to be successful. These are the people who do that. Your job will be to lead them. Thatís what you signed up for. Are you ready?

Next slide.

The guy in the second row center of this picture with a hand on his shoulder is Zack Davis. This is taken when he was a member of The Corps of Cadets at Texas A&M University. The guy on his left and right had their hands on his shoulders to keep him aligned and spaced

-- because Zack Davis is completely blind, has been since he was a little kid.

But he grew up listening to a tape of The Fightin' Texas Aggie Band, and it inspired him, and he wanted to wear the uniform of our country in some way, shape, or form, and he wanted to serve something greater than himself, and so he wrote a letter to the Commandant of Cadets at Texas A&M University, he asked to be included in the Corps and the Commandant, to his great credit, accepted him. He knew he couldnít serve in the Army or the Marine Corps or the Air Force or the Navy when he graduated, but he worried about all the same things that those who were going to did. When I first met Zack and talked to him, he told me there were three things he worried about all the time. The first was, What did the future hold after he graduated? "What am I going to do?" The second one was "Will I make a difference?" And the third one was "What are they going to expect of me in whatever career field I go into?" Iíve never forgotten that because those are the three things I worried about when I was sitting out there in this auditorium as a cadet, and I suspect they're the same three things some of you think about here. So let me talk about those three things.

Next slide.

First, let me talk about your future and start by telling you, you have absolutely no idea whatís going to happen in it. Some of you have these goals and dreams youíve had your whole life and youíll achieve them. Others have goals and dreams youíve had your whole life and youíre not even going to come close, or life will happen and youíll end up having to divert and develop a whole new set of goals and dreams and youíll succeed more widely that you thought possible. Guy in the left in this picture is my son, John. Heís a graduate of class of 2003 here at the Air Force Academy, went to pilot training, got an F‑16 out of training, which was his lifetime dream. When he was in fighter lead-in, John developed a condition called Meniereís disease; itís an inner ear disorder. He was medically grounded and then medically discharged. Big kick in the teeth for John. May of next year, John will graduate from medical school. He'll go on to a residency in orthopedic trauma surgery. Heís got a new dream, and heís chasing it a thousand miles an hour -- just like youíre going to do.

Next slide.

Mike, there, in the center just got out of the Air Force Academy. Heís an [unclear at 12:47] flight commander, RAF [Royal Air Force] in the UK. Heís got 56 Airmen working for him and they love him. Some of you knew him.

Next slide.

Kay [ph] is a Director of Public Affairs at Ramstein Air Base in Germany. She informs 54,000 Department of Defense people in the Kaiserslautern military area every single day. She's been on the job for about four months.

Next slide.

Danís a maintenance officer, Spangdahlem Air Base in Germany. His flight was spectacular in the buildup for Operation Odyssey Dawn. He was a hero. He's now been accepted in Special Operations career field. He'll switch next spring and get his beret in May.

Next slide.

Sean [O'Keefe] is the acting comptroller at the 501st Combat Support Wing in Alconbury, England. He is the principal financial adviser to the Wing Commander. Heís got 20 people working for him on four different installations. He is "the man" when it comes to money and finance for that Wing.

Next slide.

Nicole [ph] is at Ramstein Air Base in Germany. She's in a vehicle readiness squad and she runs the largest vehicle fleet in Europe, over 2000 different types of vehicle -- or 2000 different vehicles of many, many different types.

Next slide.

[Unclear at 14:09] a communications and cyber officer. He has 260 people working for him, civilians and military. He runs a network worth 54 million dollars with 22,000 users. When operations in Libya began, he was the one responsible for putting together the command and control net for air operations. He led the effort.

Next slide.

Katie [ph] is a C130J pilot at Ramstein. She's flown all over Europe and Africa. She held two -- she [helped] Libyan refugees out of Tunisia, took them back to Egypt before Odyssey Dawn began. She just got back from sitting at a static display at the Moscow Air Show.

Next slide.

Jasonís a weatherman. He works for U.S. Army Africa Staff. Heís worked on three different joint task forces already in his career.

Next Slide.

Michael [Polidor] won Jabara award for Airmanship last year. His roommate [Prichard R. Keely] from the academy won it the year before.

Next slide.

"Nasty Hickey" left here and got a -- Heís probably proud of that name. Not. He left here, went to MIT, got a Masterís degree in logistics. Then he went to F-16 school. Now, heís got a thousand hours in the F-16, 400 of them are in combat. Heís also a Homestead Scholar this next year.

Next slide.

Amy works for me on my command action group. As a lieutenant, she worked at the National Security Agency. She was credited with helping in the seizure of 40 billion dollars worth of contraband in the drug business. She's also been on the All-Air Force soccer team six times, on the All-Armed Forces soccer team six times, and was the captain of the All-Armed Services team at the [Military] World Games in Brazil this last year.

Next slide.

And "The Doc" is fully qualified in three different specialties and he has been a travelling physician for both the Chief of Staff of the Air Force and the Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld.

Next slide.

They're you. The names and faces are going to change but this is what youíre going to be doing. This and so much more. By the way, when you look at this picture, anything strike you? They got anything in common? Yeah, theyíre all smiling. They donít think where they are sucks. And by the way, if you asked them now, because I have, do you think the Academy suck because I know you said it when you were there. They all laugh and say "No". So what do you think changed, the Academy or them? Iíll leave you to chew on that for a few minutes.

[transcript verified to here: 17:11]

Next slide.

I didnít introduce the other guy in this picture to you a minute ago. Thatís my dad. His name is Mick Welch. Probably the proudest day in his life when he pinned those wings on his grandson. I donít know which one of the two is prouder in this picture, but the proudest guy in here, he was the guy taking the picture. My dad had been out of the Air Force for 30 years when John asked him to pin his wings on. He ordered a new set of class Aís. He ordered a new ribbon rack. He polished the silver insignia because his were all silver. Theyíre not chrome. This was a big event for him. A couple of years ago or three years ago, my dad died and when he died, he left us the word that in his safety deposit box he had a book that told everything we need to do after he died. So we went there to the bank and we -- we got the book out and it actually was a book and he titled, it was called the crook book. You'd like my dad. And one of the things in there, it said is "You bury me in my uniform." That uniform. So we did. While he wore that on active duty and my dad served for 35 years, he fought in three wars. He had over 9000 hours of flying time and about 8000 hours of those were in fighters, which is unheard of today. He flew with the four runners of the thunderbird, a group called the Acrojets in Germany. He towed a glider across the English Channel on D-Day. He flew a glider into Germany on the largest glider assault in history across the Rhine River and then he fought with the infantry for four months after they landed. He wore the Silver Star, five distinguished flying crosses, more air medals than I cared to count, was nominated for the Congressional Medal of Honor at one time for a mission in Vietnam. My dad made a difference and so will you.

Next slide.

Gerardís a cop, Ramstein Air Base in Germany. When our two airmen were gunned down by that spinalist guy at the Frankfurt airport earlier this year and two others critically wounded, Gerard was the first American on the scene. He led the security forces response team that took control of the site, secured the area, coordinated with the German Bundeswehr police, with the German counterterrorism police, with the OSI, the CID, the state department, and the secret service. As the on the scene commander, he put together the reports that went all the way to President Obama on what was going on. He was also responsible for the security for the two survivors who were taken to a nearby hospital.

Next slide.

Checks is meeting his wife after deployment to Afghanistan here. Checks is credited for three different times in Afghanistan saving 20-50 soldiers and special operators lives on the ground by attacking with an F-16 at the right time and putting bombs on target.

Next slide.

Neil is the guy on the right. Neil led 72 convoys in Afghanistan as convoy commander, 72. He has never lost a person or a vehicle. That is an unbelievable record. Next slide. By the way, he is a Comm officer.

Liz is a physical therapist. In fact, she was the air combat command and the U.S.AF physical therapist of the year at different times. She is also a distinguished honor grad of the U.S. Army Air Assault School. She has treated over 15,000 patients in her career so far including multiple wounded warriors, which has kind of become her specialty. She has also been on the All Air Force cross country marathon team six times.

Next slide.

Keith is a biological engineer. You heard Operation Tomodachi in Japan? The tsunami followed by the radiological disaster when the nuke plant was affected? That was the first humanitarian disaster relief effort done under radiological contaminated conditions, first time. The principal adviser to the commander of the U.S. Pacific command, the commander of the pacific air forces, and the fifth air force commander in Japan during that activity was Lieutenant Keith Sander.

Next slide.

Jane Jackson is on the right. Sheís a flight nurse. At her job currently at Ramstein Air Base in Germany, she has flown 43 evacuation flights back to the States with critical care patients, over 565 of them bringing them to life saving care in the States. The guy with her is her brother, Nat, also class of 2003. He is a KC-135 pilot in the McChord Air Base in Washington. He has almost 2000 hours of combat time. He was deployed 10 times.

Next slide.

Youíve heard these names. Joe Helton volunteered to stay six months beyond the end of his tour in Afghanistan so he could finish with the team he trained of the Iraqi police. A month after that decision, he was killed by an IED. Jeremy Fresques was a special tactics officer. He was killed on May 30, 2005 in Divala province. Right beside him fighting and dying that day was another classmate, his name, Derek Argel, the cross commission of the Navy. He was a Navy SEAL. Theyíre still resting together. Dave Wisniewski was on his third -- his third flight into a hot LZ to pull British solders off the battlefield -- wounded British soldiers off the battlefield when an RPG hit his helicopter and it crashed. Four airmen were killed and three were terribly wounded. Dave was one of the three wounded. He died about three weeks later in Bethesda Hospital in Maryland and I think you know that Roslyn Schulte was the first academy graduate female to be killed by enemy combatant. What you may not know is that she was an intelligence officer. Her job was teaching Iraqi military officials or excuse me, Afghan military officials how to collect and interpret intelligence. That job made her a target and she was killed outside of Kabul by an IED. These people made a difference. Everybody I just talked about is making a difference, and you will too. Donít worry about that.

Next slide.

After that day where you smoked cigars, lay on the grass, chest bumped the president and make a fool out of yourself on national TV , youíre going to come out and work with the rest of us. Let me tell you what we expect.

Next slide.

We expect you to be credible, not like that guy, but like number 35. Thatís my son, Matt. See when you get me, you get the whole family. This is an 8 to 9-year-old basketball team called the Lakers. Iím coaching it because Matt was a 7 year old and I didnít want him to play with 6 and 7 year olds because he has always been about two bubbles off center and I was afraid heíd hurt somebody so I thought 8 and 9 year olds were a lot bigger and weíll be safer. The guy in the back row, there number 33 is Thomas. Thomasí dad called me after we had tryouts and we had the team set and he said "Hey! The league chairman said maybe I could have my son play in your team." And I said okay. This sounds a little fishy to me about Thomas, so he told me how tall he was and I went "Hmm? That would be a good thing." and then he told me he had attention deficit disorder. I mean he really had ADD, but I met Thomas. Heís a great kid so I said sure, Iíd love to have him on the team.

Well, Thomas was a horrible basketball player. I mean they called him Bunny, which was short for energizer bunny. I mean every time he got the ball, heíd start vibrating. So, he'd do this and eventually, he just vibrated a travelling call and weíd go play defense. It happened that way all year long. Right before the first game of the season, during the practice, Thomas came up to me, itís a Thursday night, weíre playing Saturday, he said "Coach, can I talk to the guys?" Sure Thomas. Inspire us.

So we gathered as a team around and Thomas tells them a story. He tells me how he got his nickname. Turns out Thomas is the only guy in our team who wasnít from the same elementary school. He came from another school. The reason heíd move is because he couldnít play with the kids from his own school because they made fun of him all the time and they did. The big score on the team we're playing Saturday, kind of the league stars, the one who gave him the nickname Bunny, which was actually a pretty good nickname. But Thomas just poured out his heart to the team about how these guys picked on him at school all day. He tries hard to ignore it, but he knows it will happen again during the game and he just wanted the team to know that he probably wouldnít play very well on Saturday, which I think they knew anyway.

But he was kind of cool. What was really cool was when he was done, Matt stood up, put his arm around his -- about his waist, which is where he could reach. He says, "Donít worry Thomas. They wonít say anything to you with me around" Thatís my boy. Saturday rolls around. Weíre doing the lay-up line. Thomas has his usual, you know, he whiffs everything with a layup, he doesnít even get glass, twine, nothing. Some kids from the other end yells, "Hey look at Bunny shoot!" Matt peels out of our layup line and screams at them "You better shut up" and I grabbed Matt and throw him back in line.

We got ready to start the game. I sent Thomas out to start, one of the jump center, I thought weíd give him a little street credit with his peeps, so he heads out there kind of vibrating. You know, doing the -- into the circle and of course, not knowing that the kid who picks on him all the time is going to jump against him, so a bad move by the coach. And as he walks out there, this kid looks at Thomas, starts laughing, turns to one of the other kids on his team, he states, "Hey look at Bunny vibrate!" and Matt went Rambo on him. He took him out. He took him down. Heís flailing. Heís pounding on him right there in the middle of the circle. The referees got the ball in his hand going "What do I do with this?"

Finally, he drops the ball, picks up Matt. He kind of walks over and I grabbed him. Matt is still screaming, I throw him into the bench. We havenít started our first game of the year and my son is already thrown out. Itís a horrible moment for Betty and I. Anyway, things calmed down. Game gets ready to restart. The kid in the other still got a little blood on his lip but heís doing okay. Heís back out on the floor and Thomas now comes walking out like John Wayne. He steps in front of the guy and he points over at Matt on the bench, and he says, "Heís still right there."

Matt has credibility. He still does by the way. If he says that he means it. If he tells you heís going to kick your butt, you got a decision to make because heís going to try. You need to have that kind of credibility when you leave here. You need to develop it here. When you tell your airman leader that youíre going to do something for him, you better do it. If you tell him youíre going to follow up on an action form, you better follow up. If you tell him youíre going to look into something for their family, you better look into it. Folks, you get one chance. One chance. Get ready.

Next slide.

We talk here a lot about attention to detail. I know you do. You do this here all the time. You guys are trying to train him. People told you the same thing. Most of time, youíre going, "Why does this matter?" You know the fact that your socks are rolled a certain way don't matter. It's the fact that you pay attention to detail.

These are my buddies. They are Mike Gouldís buddies. McGoo is Mike McGuire. Mike McGuire died in an F-4 accident. Got a little distracted doing a nuclear bomb toss, rolled over, as he started to pull, he kind of drifted the nose low watching the bomb probably and not paying attention. He hit the ground going real fast. The board decided that if you started to roll and pull 0.2 seconds earlier, he might have lived; 0.2 seconds. Dave Meyer [ph] was flying his number four on an A-7 flight in Turkey. We called "Yamoo" [ph] 'cause it means "little mountain" supposedly in Japanese and he was a big boy, played "O-Line" on the football team, one of the nicest human beings that I have ever met. He went lost wingman when his flight went above the weather for a weather abort. Nobody really understand what -- understood why he went lost wing and then they just realized later he flew almost straight ahead probably looking up in the air for his flight because he couldnít hear them on the radio and flew into the ground. In the investigation they determined that his volume knob on his radio have been turned down probably when bumped it with his glove reaching for a switch nearby. Seems like such a little thing, doesn't it?

John Vosberg was flying 22 feet low on a low level route in Korea. He was certified to 100 feet, he was about 22 feet. Didnít have a radar altimeter. Hard to tell 22 feet. Unfortunately, there was a new cable that was strung at 78 feet above the ground and when he turned into the sun, another minor mistake, and because of the glare, he couldnít see it, it hit his OV-10 and disintegrated in midair.

Cheeko Lavelle was crouched on the front seat of his F-4 at [31:32] Air Force base, waiting to do a ground egress because they had a fire behind them. Somehow, he and the back sitter had gotten the terminology confused and when one of them said get out, the other guy thought he meant bail out and ejected him and he was decapitated by the canopy reel. Attention to detail. Is it important? You decide. But when you leave here, you better have it.

Next slide.

You better be ready to make decisions as well. First Gulf War, I was flying an F-16 mission, first day of the ground war. A bunch of us were up on a common strike frequency and a guy named Bill Andrews was shot down right in the middle of the retreating Republican Guard armored division. Strike control came up on the frequency and said, "We got an F-16 down. Hereís the coordinates." So, everybody was looking at their map trying to figure out where this was. I need anybody with the weapons in the field to support a search and rescue effort to call back, and as Iím looking at these coordinates, looking at my map, I was doing the same thing everybody else in the air was doing, which is thinking "Oh man. That is a bad place to be on the ground" and there was a deadly silence on the radio. Until an Army helicopter pilot came on. Flying one of these things, the Chinook, and pilot said, "Look, Iíve got the gas. I can get there. Iíll go pick him up." Iím thinking, "thatís the size of a double-decker bus in London. Itís got no guns and youíre going to fly that thing into the middle of a retreating Iraqi armored division to pick up one pilot?" First on my life, Iíve ever said "Hooh-Hah". I was impressed. Shortly thereafter, we had a call saying that heíd been captured. They cancelled the search and rescue effort and that Chinook never had to make an attempt. That pilot never had to prove that they were really willing to do it, but I never forgot that radio call and Iíll never forget her voice. First time I told this story when I got back from the gulf war, one of the people in the audience came up to me afterwards and said, "I know who that was. I just got out of the army. The only person that could have been is Major Marie Rossi."

Next slide.

"She was the only combat-certified aircraft commander in the United States Army at that time" so I went looking for her and sure enough, he was right. It was Major Marie Rossi, and once I confirmed that was her name. I said, "Iím going to go meet here. I want to tell her ĎThank youí because she was inspirational at a time when people needed it." It took me a little while to find her.

Slide.

But I did. Two days after the war ended, she and her crew were called out at two in the morning to pick up a soldier whose arms have been blown up by trying to pick up weapons that were left from air-drop cluster munitions. She picked him up and was heading back to their base on the Saudi-Kuwait border when -- or the Saudi-Iraq border, excuse me, when they hit an unlit radio tower. The helicopter crashed and they were all killed. She lives here now in one of the newer sections of Arlington National Cemetery and I kept my promise. I went and met her and I stood in front of that rock and thanked her for courage, for her dedication, for the inspiration she gave so many of us that day, for her sacrifice, and the sacrifice of her husband and her young daughter. My son Matt is still not a really touchy feely kind of guy. When I told him the story, he goes, "Hey dad you must felt pretty stupid standing there talking to that rock." At attention, which I was, I donít know why, and I answered him, "Actually, not stupid, just proud. You better be willing to make decisions because youíre going to need to and youíre going to need to make them without all the information youíd like and youíre going to need to make them when peopleís lives are at stake and youíre not going to always have time to ask for somebody else to help you. Get ready.

Next slide.

When I was a Wing Commander in Kunsan, Korea, at a 4th of July picnic and my chief master sergeant and I were standing there and we looked up to the side walk, and thereís a guy walking toward us and heís got black combat boots, black knee socks, cut off jean shorts, no shirt, heís got nipple rings, heís got a chain between them and the chain is connected to a black leather dog collar with big silver spikes on it, which matched the one on his wrist. He had the Hitler kind of haircut, golf black, so the chief and I went over and talked to him and gave him some fashion advice, which Iím sure he appreciated.

Turns out heís an F-16 crew chief, [unclear at 37:05] staff sergeant, great guy, fantastic crew chief I came to find out. I flew his airplane a lot. Every night, probably a couple of nights a week, I drive through the flight line and the visit the guys out there. He was on the swing shift, which is the afternoon-evening shift so I got to see him a bunch. I got to know him pretty well. We talked two or three times a week. Maybe six to seven months into my tour there, I get a knock on my door on Friday night, late, I'm in the office doing paperwork. I look up and hereís this young staff sergeant and with him is this tech sergeant supervisor, brand new to the wing, been there about four days and he and the Squadron commander first sergeant chief were all behind him looking not happy to be there and this tech sergeant dragged him to my office and he said, "Boss, you got to fix this" and Iím thinking God, he took his shirt off in the flight line. He had those nipple rings again, this is horrible.

And then that young tech sergeant explained to me that wasn't the problem, this was the problem, his daughter Lori, who was four years old. The guy had left Hill Air Force Base in Utah to come to Korea. He got a divorce right before he left because his wife was on drugs and he couldnít get her to stop using them and after exhausting every other possibility, he divorced her. They had a custody battle for Lori. He didnít want his wife to get in trouble with the law so he didnít mention the drugs and she got custody of her daughter. Since then, she had been arrested, charged, convicted of felony drug sales and she was going to prison. Her only surviving relative and his only surviving relative was her mother who had just gotten out of prison for drug sales. The judge had said, "whoever gets custody is going to be close enough that I can see this little girl every six to eight weeks because Iím worried about her." So he canít compete because his follow on assignment is to Spain down to Germany, so for the last six months, heíd been trying to work the air force assignment system on his own as a staff sergeant from Kunsan to get an assignment change.

You can imagine the kind of luck he was having. Heís a very proud guy, he didnít want to ask for help. Well, after hearing the story, we kind of confirm some facts, I called up the judge, talked to him. He agreed that at the final custody hearing, which was Monday, this is Friday night in Korea, he could compete if he was living closer. So I called the guy named Jimmy Green, who ran the assignment system, good friend of Mike Gouldís said, "Jimmy, I need some help." I told him the story. Jimmy said, "What do you want?" I said, "I wanted him to be assigned to Luke Air Force Base and I wanted him to be there Sunday." He said, "Okay. Put him on the airplane. The orders will meet him."

So we did after we gave him a little advice about what you wear to a custody hearing in front of a judge and how to get a haircut between now and then. Anyway, I didnít hear anything else about this for a couple of months and one Friday evening, again Iím in the office. Itís dark outside. I opened up an envelope. I donít recognize the writing on and this picture falls out along with a note that just says "Thank you. This is Lori at her fifth birthday party at the Animal Park up near Flagstaff, Arizona. I have full custody of her now." Pretty cool story, isn't it? Let me ask you a really important question. Why didnít I know about Lori? Saw the guy all the time. Talked to him a couple of times a week. Why didnít I know he had a daughter? Any guesses? Itís not complicated. I never asked him. I never asked him. I almost cost him his daughter. I almost cost her a family. By the way, so did his Squadron commander, group commander, chiefs, first sergeants; none of them asked him. That young tech sergeant was leading this kid. Four days on the job, he knew all about Lori. Folks, every airman has a story. Everybody in this room has a story. If you donít know the story, you canít lead the airman. Itís that simple. Please learn the story.

Next slide.

Weíre going to expect you to be committed when you walk out the door. This is my command chief, his name is Dave Williamson. Heís a pretty impressive guy. Heís an explosive ordinance disposal technician. You could see heís wearing three specialty badges. Heís got 36 ribbons on his chest and more, you know, Stars and Oakleys than you can care to count here. Heís been a distinguished graduate of every PMA course he ever attended including the U.S. Armyís one year sergeant major academy where he was the distinguished graduate, the commandantís award winner and won the physical fitness award. Not normal for an air force guy in that environment. He has had 14 combat zone deployments. The last two as a command chief on one year tours, one in Afghanistan and one in Iraq. The previous twelve were all as an EOD technician or EOD team chief with army and Marine Corps units in all the ugliest places you can imagine. This guy expects you to be committed to this profession. He expects you to be running as fast as you can when you hit the ground because if youíre not, he knows we will blow your doors off and leave you spinning on the side of the road because thatís what will happen and he expects you to be ready to lead his airman. In fact, he demands it. Airman like this next guy.

Slide.

Let me show you a video of a retirement ceremony. I'm not going to say anything about it. It's a young staff sergeant, you guys will see hundreds of this in your career. Can we run this, Fred?

"I want to thank the Air Force for giving me the honor and privilege to carry my country's flag into battle. It's a [43:16] for a first job and career became a great, great joy, every day I loved how we work, and after a short period of time, I gained a great sense of purpose in what I did. And I think now that [43:37] I've thought of what I'm going to miss the most: this wonderful family and this great sense of purpose, and I hope to take it with me wherever I go. Thank you."

Mike, can I ask you and Betty to start walking up here to the side of the stage? Do you mind joining me for a minute here in just a second? I wasn't quite telling you the truth. This really isnít a retirement ceremony. It's an award ceremony.

Next slide.

There's an air force staff sergeant named Matt Slaydon. Mattís another EOD techinician. You couldnít see very well in that picture because it's kind of a cheesy audio and a video. The first line, in case you didnít catch it was, "I want to thank my nation for the privilege of carrying this country as my flag in the battle." Whatís impressive about that is the other stuff you couldnít see in that photo. You couldnít tell from that that Matt Slaydon doesnít have a left arm. As a team chief, he was checking a bomb in Afghanistan and as he took a look, he noticed the command detonation wire running off to the side. Something had felt wrong about it when he pulled up and so he left the rest of the team in their van protected. He saw the command detonation wire had just enough time to stand and turn, which exposed his left side of the bomb when the coward at the other end of the fuse set it off. His left arm was blown off instantly. His left eye was blown out. He had shrapnel in the entire left side of his body. He had third degree burns on his neck and face. His right eye was damaged beyond repair. Heís blind, and heís saying things like that at an award ceremony. Are you ready to lead him?

Next slide.

Let me leave you with these words. Leadership is a gift. Itís given by those who follow, but you have to be worthy of it. The men and women that youíre going to be responsible for are the greatest people in the planet. You better be getting ready to lead them. If youíre not, rededicate yourself to the effort. Try your leadership skills here. If you fail, learn and move on, try again. Thatís what this environment is for. If youíre still saying this place sucks, leave. We donít need you. We donít want you. We donít have time for you. Because when you leave this place and I put you in command and supervision of people like Matt Slaydon, if you let them down, I will track you down, and I will hurt you and thatís going to be really embarrassing considering how old I am. Is that fair? Guys, do join me.

Next slide, please, Fred.

Few minutes ago, I told you about John Vosberg, would you guys come out here with me? But I didnít tell you everything about him. Vos was my roommate here. He was my classmate in pilot training. He was my best friend. Heís my brother-in-law. Bettyís brother. Heís the godfather of our first child. Heís like the people sitting next to you. The bonds you form here will not end. Vos died November 28, 1979, and after they found his remains off the coast of Korea, they shipped him to the west coast of the U.S. and I met him at the Oakland Army Depot to take him home to New York and then I said on top of his coffin in an empty supply hangar waiting for a flight to New York, I made him a promise. I promised that every year, sometime in the month of November, Iíd toast him with people I knew heíd respect. Well, this is November and you qualify. Guys, would you come out here and join me? Iíd appreciate it. He shall not grow old as we who are left grow old. Age shall not worry him nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun, and in the morning, we will remember. To John Vosberg, fighter pilot, classmate, my friend, and our brother. Thank you for the life youíve chosen. Thanks for being good enough to be here. Make sure youíre good enough to graduate, and take care of yourselves.

Iíll see you out there.

Youíre dismissed.

Note: Error alerts for this transcription are welcome and appreciated. Please send an email with the error and your correction to: owner@americanrhetoric.com. Use subject line "Gen. Welsh transcription error".

Audio and Image #1 Source: http://www.dvidshub.net/

Image of Graduate Wall Memorial Source: usafalibrary.com

Image of Bart Decker Source:

Wikipedia.org

Audio Note: AR-XE = American Rhetoric Extreme Enhancement

Page Updated: 1/3/21

U.S Copyright Status: Text, Audio, Image = Public domain.