|

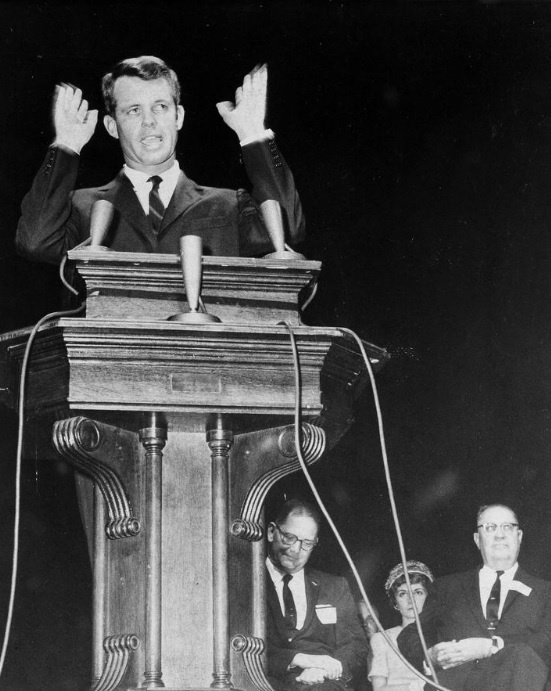

Robert F. Kennedy Law Day Address at the University of Georgia School of Law delivered 6 May 1961, Athens, Georgia

[AUTHENTICITY CERTIFIED: Text version below transcribed directly from audio.] ...but I am happy to be here. I, as Attorney General, I feel a little bit like the rabbi up in Massachusetts who had a son here during the -- in the state of Georgia during the war and he fell in love with a young Georgia girl. And the son wrote the rabbi and said I want to get married. And the rabbi first opposed it because the girl wasn't Jewish and then finally decided that he'd allow his son to get married. And then the son wrote him and said, "Well I want you to come down here. I want you to come down and marry us." Well he [the rabbi] had a good deal of reluctance to do it, but finally he got on a plane and he flew down and, took a train and then a bus; got off in a small Georgia town. And he had a long beard -- he was a rabbi, orthodox rabbi -- and a black hat. He was dressed in all his black robes. And he walked down the middle of this Georgia town, and some children saw him. They'd never seen anything like this and they started to follow him. And he walked for another two or three blocks and more and more children followed him. Finally he got to almost the edge of town and there was just an enormous flock of children looking at him, wondering. So finally he turned around and said, "Haven't you ever seen a Yankee before?" I understand that the last Attorney General who came down into the South, he -- that was Mr. Rogers -- he hid in a plane in South Carolina. That -- That wasn't very successful in South Carolina so I'm trying the other approach. So we'll see how it all works out. But I am happy and pleased to be here because the University of Georgia and the University of Georgia Law School have such fine traditions. And those who have contributed to our public life from the state of Georgia are an inspiration to all of us. Senator Russell, with whom I have been associated at various times -- I don't there's anybody in the United States Senate for whom people have generally more respect than -- than Senator Russell. Senator Talmadge, since he's been up in Washington, who all of us -- no matter what side of the political fence we might be on -- have such great respect. And your governor here, Governor Vandiver, has been such a fine friend of my brother and myself; and then Senator George when he was alive who was such a great friend of my father's; so we feel very close to the state of Georgia. This is the first time since becoming Attorney General three months ago that I have made a formal speech, and so I am proud to do it in the state of Georgia. Two months ago I had a very great honor to present to the President Donald Eugene McGregor of Brunswick, Georgia. Donald McGregor came to Washington to receive the Young American Medal for Bravery. In twelve bad hours he led a family of four to safety from a ship that had broken up off the high seas in the Georgia coast. He impressed all of us who met him with his courage. And as the President said, "Donald McGregor is a fine young American, one of a long line of Georgians who have by their courage set a -- an outstanding example for their fellow Americans." They have told me that when you speak in Georgia, you should try to tie yourself to Georgia and to the South, and even better claim some Georgia kinfolk. There are a lot of Kennedy's in Georgia, but as far as I can tell, I have no relatives here, and no direct ties to Georgia except one: This state gave my brother the biggest percentage majority of any state in the Union, and in that last election that was more important than kinfolk. We meet at this great university, in this old state, the fourth of the original thirteen, to observe "Law Day." In his proclamation, urging us to observe this day, the President emphasized two thoughts. He pointed out that to remain free, the people must (quote), "Cherish their freedoms, understand their responsibilities that they entail, and nurture the will to preserve them." He then went on to point out that (quote), "Law is the strongest link between man and freedom," (unquote). I wonder in how many countries of the world people think of law as the link between man and freedom. We know that in many, law is the instrument of tyranny. And people think of law as little more than the will of the state, or the party, but not of the people. And we know, too, that throughout the long history of mankind man has had to struggle to create a system of law and government in which fundamental freedoms would be linked with the enforcement of justice. We know that we can not live together without rules which tell us what is right and what is wrong, what is permitted and what is prohibited. We know that it is law which enables man to live together, that creates order out of chaos. We know that law is the glue that holds civilization together. And we know that if one man's rights are denied, the rights of all of us are in danger. In our country the courts have a most important role in safeguarding these rights. The decisions of the courts, however much we might disagree with them, in the final analysis must be followed and must be respected. If we disagree with a court decision, and thereafter irresponsibly assail the court and defy its rulings, we challenge the foundations of our society. The Supreme Court of Georgia set forth this proposition quite clearly in 1949 in the case of Krum [ph] versus the State. The court, referring to United States Supreme Court decisions, said there (and I quote), "And whatever may be the individual opinion of the members of this court as to the correctness, soundness, and wisdom of these decisions, it becomes our duty to yield thereto just as other courts in this state" must be -- "must accept and must be controlled by the decisions and mandates of this court. This being a government of law and not of men, the jury commissioners in their official conduct are bound by the foregoing rulings of the Supreme Court of the United States, notwithstanding any personal opinion, hereditary instinct, natural impulse, or geographical tradition to the contrary," (unquote). "Respect for the law," in essence, that is the meaning of Law Day. And every day must be Law Day, or else our society would collapse. The challenge which international Communism hurls against the rule of law is very great. For the past two weeks I have been engaged for a good part of my time, in working with General Taylor, Admiral Burke and Mr. Dulles, to assess the recent events in Cuba, and to determine what lessons can -- we can learn for the future. It already has become crystal clear in our study that as the President stated so graphically, "We must reexamine and reorient our forces of every kind. Not just our military forces, but all our techniques and even our outlook here in the United States." We must come forward with the answer of how a nation devoted to freedom and individual rights and respect for the law can stand effectively against an implacable enemy who plays by different rules and knows only the law of the jungle. With the answer to this rests our future, our destiny as a nation and as a people. The events of the last few weeks have demonstrated that the time has long since passed when the people of the United States can be apathetic, about their belief and respect for the law, and about the necessity of placing our own house in order. As we turn to meet our enemy, we look him full in the face; we can not afford feet of clay or an arm of glass. Let me speak to you about three major areas of difficulty within the purview of my responsibilities that sap our national strength, that weaken our people, that require our immediate attention. In too many major communities of our country, organized crime has become big business. It knows no state lines; it drains off millions of dollars of our national wealth, infecting legitimate businesses, labor unions, and even sports. Tolerating organized crime promotes the cheap philosophy that everything is a racket. It promotes cynicism amongst adults. It contributes to the confusion of the young and to the increase of juvenile delinquency. It is not the gangster himself who is of concern. It is what he is doing to our cities, our communities, our moral fiber. Ninety percent of the major racketeers would be out of business by the end of this year if the ordinary citizen, the business man, the union official, and the public authority stood up to be counted and refused to be corrupted. This is a problem for all America, not just the Federal Bureau of Investigation, or the Department of Justice. Unless the basic attitude changes here in this country, the rackets will prosper and grow. Of this I am convinced. The racketeers after all are professional criminals. [They] are also the amateurs, men who have law abiding backgrounds and respectable positions, who nevertheless break the law of the land. We have been particularly concerned lately in the Department of Justice about the spread of illegal price fixing. I would say to you, however, this is merely symptomatic of many other practices commonly accepted in business life. Our investigations show that in an alarming number of areas of the country businessmen have conspired in secret to fix prices, made collusive deals with union officials, defrauded their customers, and even in some instances cheated their own government. Our enemies assert that capitalism enslaves the worker and will destroy itself. It is our national faith that the system of competitive enterprise offers the best hope of individual freedom, social development, and economic growth. Thus every businessman who cheats on his taxes, fixes prices, or underpays his labor, every union official who makes a collusive deal, misuses union funds, they damage the free enterprise system in the eyes of the world, and do a disservice to the millions of honest Americans in all walks of life. Where we have evidence of violations of the law by these "respectables," we will take action against the individuals involved as well as against their companies. But in the end this also is not a situation which can be cured by the Department of Justice. It can only be cured by business and unions themselves. The third area is the one that affects us all the most directly -- the field of civil rights. The hardest problem of all in law enforcement are those involving a conflict of law and local customs. History has recorded many occasions when the moral sense of a nation produced judicial decisions such as the 1954 decision in Brown versus the Board of Education which required difficult local adjustments. I have many friends in the United States Senate who are southerners. Many of these friendships stem from my work as counsel for the Senate Rackets Committee, headed by Senator John McAllen of Arkansas for whom I have the greatest admiration and affection. If these southern friends of mine are representative Southerners, and I believe they are, I do not pretend that they believe with me on everything, or that I agree with them on everything. But knowing them as I do I am convinced of this: Southerners have a special respect for candor and plain talk. They don't like hypocrisy. So in discussing this third major problem, I must tell you candidly what our policies are going to be in the field of civil rights and why. I come to you in that spirit. First let me say this. The time has long since arrived when loyal Americans must measure the impact of their actions beyond the limits of their own towns or states. For instance, we must be quite aware of the fact that fifty percent of the countries in the United Nations are not white; that around the world in Africa, South America, and Asia, peoples whose skins are a different color than ours are on the move to gain their measure of freedom and of liberty. From the Congo to Cuba, from South Viet Nam to Algiers, in India, Brazil and Iran, men, women, and children are straightening their backs and listening to the evil promises of Communist tyranny, and the honorable promises of Anglo American liberty. And those people will decide not only their own future, but ours; how the cause of freedom fares around the world. That will be their decision. In the United States, we are striving to establish a rule of law instead of a rule of force. In that forum and elsewhere around the world our deeds will speak for us. In the worldwide struggle, the graduation at this university of Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes will, without question, aid and assist the fight against communist political infiltration, and even guerilla warfare. When parents send their children to school this fall in Atlanta, peaceably and in accordance with the rule of law, barefoot Burmese and Congolese will see before their eyes Americans living by the rule of law. The conflict of views over the original decision in 1954 and our recent move in Prince Edward County Virginia is understandable. The decision in 1954 required action of the most difficult, delicate, and complex nature, going to the heart of Southern Institutions. I know a little of this. I live in Virginia. I studied law at the University of Virginia. I have been privileged to know many able southern soldiers, scholars, lawyers, jurists, journalists, and political leaders who have enriched our national life. From them I have drawn some understanding of the South. But my knowledge is nothing to yours. It is now being said, however, that the Department of Justice is attempting to close all public schools in Virginia because of the Prince Edward situation. This is simply not true; nor is the Prince Edward suit a threat against local control. We are maintaining the orders of the court. We are doing nothing more and nothing less. And if any one of you were in my position you would do likewise, for it would be required by your oath of office. You might not want to do it. You...might not like to do it. But you would do it because it would be required. And beyond that, I can not believe that anyone can support a principle which prevents more than a thousand of our children in one county from attending public school, especially when this step was taken to circumvent the orders of the court. Our position is quite clear. We are upholding the law. Our action does not threaten local control. The federal government would not be running the schools in Prince Edward County any more than it is running the University of Georgia or the schools in my state of Massachusetts. In this case, in all cases, I say to you today that if the orders of the court are circumvented, the Department of Justice will act. We will not stand by and be aloof -- we will move. Here on this campus about a half a year ago you endured a difficult ordeal. And when your moment of truth came the voices crying "force" were overridden by the voices pleading for reason. And for this I pay my respects to your governor, to your legislature, and most particularly to you, the students and faculty of the University of Georgia. And I say that you are the wave of the future, not those who cry panic. For the country's future, you will and must prevail. I happen to believe that the 1954 decision was right. But my belief does not matter. It is now the law. Some of you may believe the decision was wrong. That does not matter. It is the law. And we both respect the law. By facing this problem honorably you have shown to all the world that we Americans are moving forward together, solving this problem under the rule of law. An integral part of all of this is that we make a total effort to guarantee the ballot to every American of voting age -- in the North as well as in the South. The right to vote is the easiest of all rights to grant. The spirit of our democracy, the letter of our constitution and our laws require that there be no further delay in the achievement of full freedom to vote to all. Our system depends upon the fullest participation of all its citizens. The problem between the white and the colored people is a problem for all sections of the United States. And as I have said before I believe there has been a great deal of hypocrisy in dealing with it. In fact I found, when I came to the Department of Justice, that I need look no further to find evidence of this. I found that very few Negroes were employed above a custodial level. There were nine hundred and fifty lawyers working in the Department of -- the Department of Justice in Washington, and only ten of them were Negroes. At the same moment the lawyers at the Department of Justice were bringing legal action to end discrimination, that same discrimination was being practiced in the department itself. At a recent review for the visiting leader of a new African State, there was only one Negro in the guard of honor. At the bureau of budget Negroes were used only for custodial work. The federal government is taking steps to correct this. Financial leaders from the East who deplore discrimination in the South belong to institutions where no Negroes or Jews are allowed. And their children attend private schools where no Negro students are enrolled; union officials who criticize Southern leaders and yet practice discrimination within their own union; government officials belong to private clubs in Washington where Negroes including ambassadors are not welcome even at meal time. My firm belief is that if we are to make progress in this area, if we are to be truly great as a nation, then we must make sure that nobody is denied an opportunity because of race, creed, or color. We pledge by example to take action in our own back yard, the Department of Justice. We pledge to move to protect the integrity of the courts in the administration of justice. In all this we ask your help. We need your assistance. I come to you today, and I shall come to you in the years ahead to advocate reason and the rule of law. It is in this spirit that since taking office I have conferred many times with responsible public officials and civic leaders in the South on specific situations. I shall continue to do so. I don't expect them always to agree with my view of what the law requires. But I believe that they share my respect for the law. We are trying to achieve amicable, voluntary solutions without going to court. These discussions have ranged from voting and school cases to incidents of arrest which might lead to violence. We have sought to be helpful to avert violence and to get voluntary compliance. When our investigations indicate there has been a violation of law, we have first asked responsible officials to take steps themselves to correct the situation. In some instances, this has happened. When it has not, we have had to take legal action. These conversations have been devoid of bitterness or hatred. They have been carried on with mutual respect, understanding, and good will. National unity is essential, and before taking any legal action, we will, where appropriate, invite the southern leaders to make their views known in these cases. We, the American people, must avoid another Little Rock, or another New Orleans. We can not afford them. It is not only that such incidents do incalculable harm to the children involved and to the relations among people. It is not only that such convulsions seriously undermine respect for law and order and cause serious economic and moral damage. Such incidents hurt our country in the eyes of the world. We just can't afford another Little Rock, or another New Orleans. For on this generation of Americans falls the full burden of proving to the world that we -- we really mean when we say -- we really mean it when we say that all men are created free and equal before the law. All of us might wish at times that we lived in a more tranquil world but we don't. And if our times are difficult and perplexing, so are they challenging and filled with opportunity. To the South, perhaps more than any other section of the country, has been given the opportunity and the challenge and the responsibility of demonstrating America at its greatest -- at its full potential of liberty under law. You may ask, will we enforce the civil rights statutes? And the answer is yes, we will. We also will enforce the antitrust laws, the antiracketeering laws, the laws against kidnapping and robbing federal banks, and transporting stolen automobiles across state lines, the illicit traffic in narcotics and all the rest. We can and will do no less. I hold a constitutional office of the United States government, and I shall perform the duty I have sworn to undertake to enforce the law in every field of law and every region. We will not threaten -- we will try to help. We will not persecute -- we will prosecute. We will not make or interpret the laws. We shall enforce them vigorously, without regional bias or political slant. All this we intend to do. But all the high rhetoric on Law Day about the noble mansions of the law, all the high sounding speeches about liberty and justice are meaningless unless people such as you and I breathe meaning and force into it. For our liberties depend upon our respect for the law. On December 13th, 1889, Henry Grady of Georgia said these words to an audience in my own home state of Massachusetts:

Ten days later, Mr. Grady was dead, but his words live today. We stand for human liberty. The road ahead is full of difficulties and discomforts. But as for me, I welcome the challenge. I welcome the opportunity, and I pledge to you my best effort -- all I have in material things and physical strength and spirit to see that freedom shall advance and that our children will grow old under the rule of law. Thank you very much.

Technical Note: Audio volume dips in several places, most notably from 5:55-6:14 and 9:23-9:29. Audio Source: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum Image Source: The National Archives and Records Administration Page Updated: 1/7/22 U.S. Copyright Status: Texts and audio = Property of AmericanRhetoric.com. Image (AP Photo/Horace Cort) = Fair Use. |

|

|

© Copyright 2001-Present. |